N° 5

History

April 2018

by Pascale Girardin illustration by pascale girardin

In contemplating a theme for this issue, I looked to Black History Month. My idea was to reach out to artists of colour from across North America and ask them to share stories from history that have special significance to them.

I planned to publish the interviews I collected in Drift all year long. After all, why be limited to a month?

But in the background, I questioned my own motivations. I kept wondering, “Why am I interested in this? I’m white.” This thought put me into a weird space, a kind of feedback loop in which I ossilated between “we all belong in the conversation” and “this not my place.”

After seeking the council of a trusted friend well versed in black history, I veered my inquiry to the broader topic of history as a social construct with a dominant narrative. To free ourselves from it, we must acknowledge that there are numerous versions of history. It’s only by being receptive to this multifaceted definition that we can better understand one another. We have to – because every day, we’re making history as well.

So in this issue, we explore history first through the perspective of ancestry, then through the lens of jazz, one of my favourite musical genres, and a theme that came up again and again in the conversations I had with the people who contributed to this issue.

In Harlem of the North, DJ Andy Williams tells of the nearly forgotten inter-war jazz golden age in Montreal; This is not a Tree looks at the multitude of lives that went into the creation of our own; and Blue Note explores the work of Jennie C. Jones, an artist who uses the unlikely aesthetic of minimalism to actually call into question black music’s exclusion from modernist visual art.

“Drift” is my way of explaining how meandering thoughts can crystallize into a fully formed idea. It’s the origin of creative thinking and my mantra for daily life.

I invite you to drift with me.

Pascale Girardin

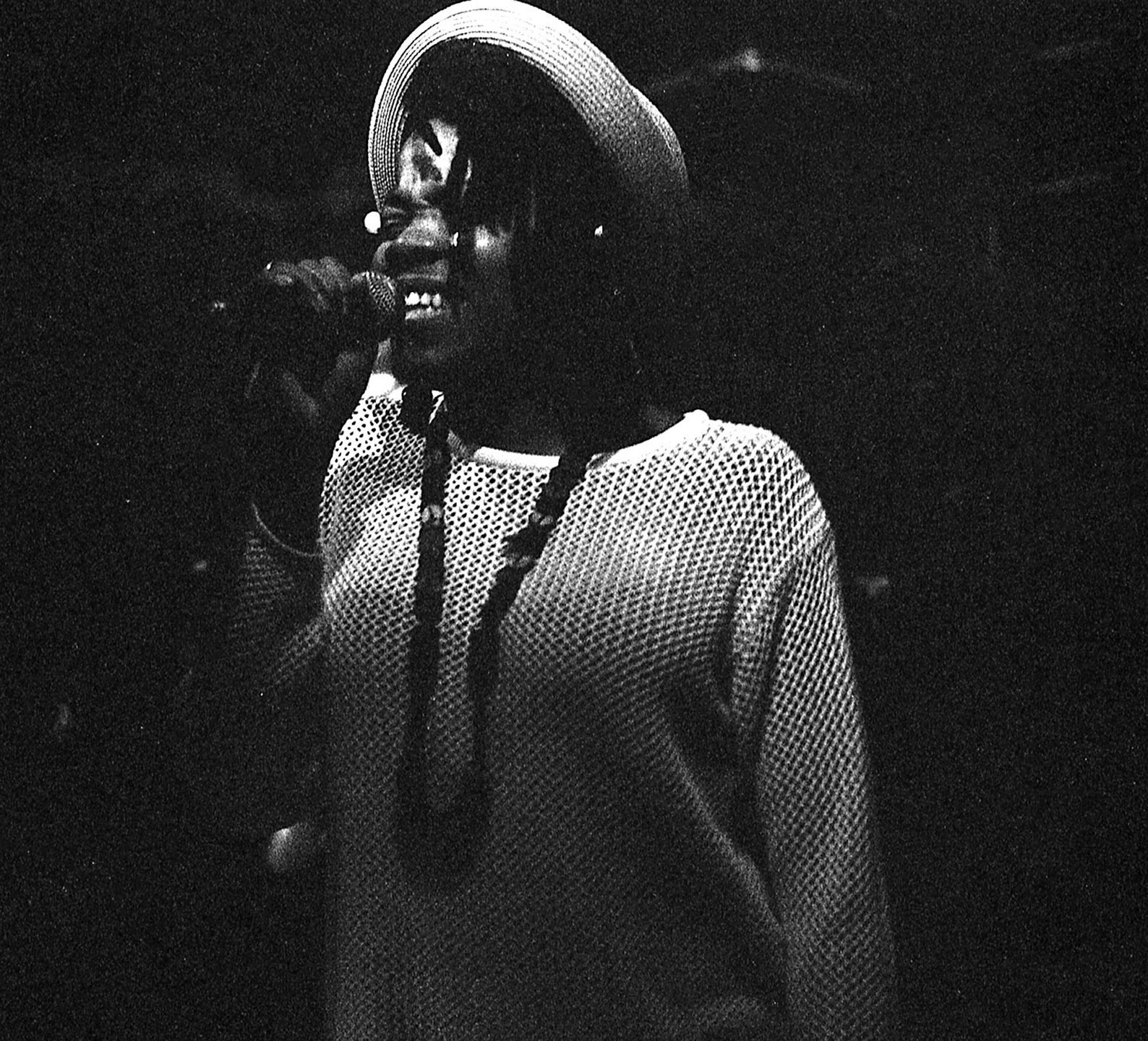

by pascale Girardin photo by Saad Al-Hakkak

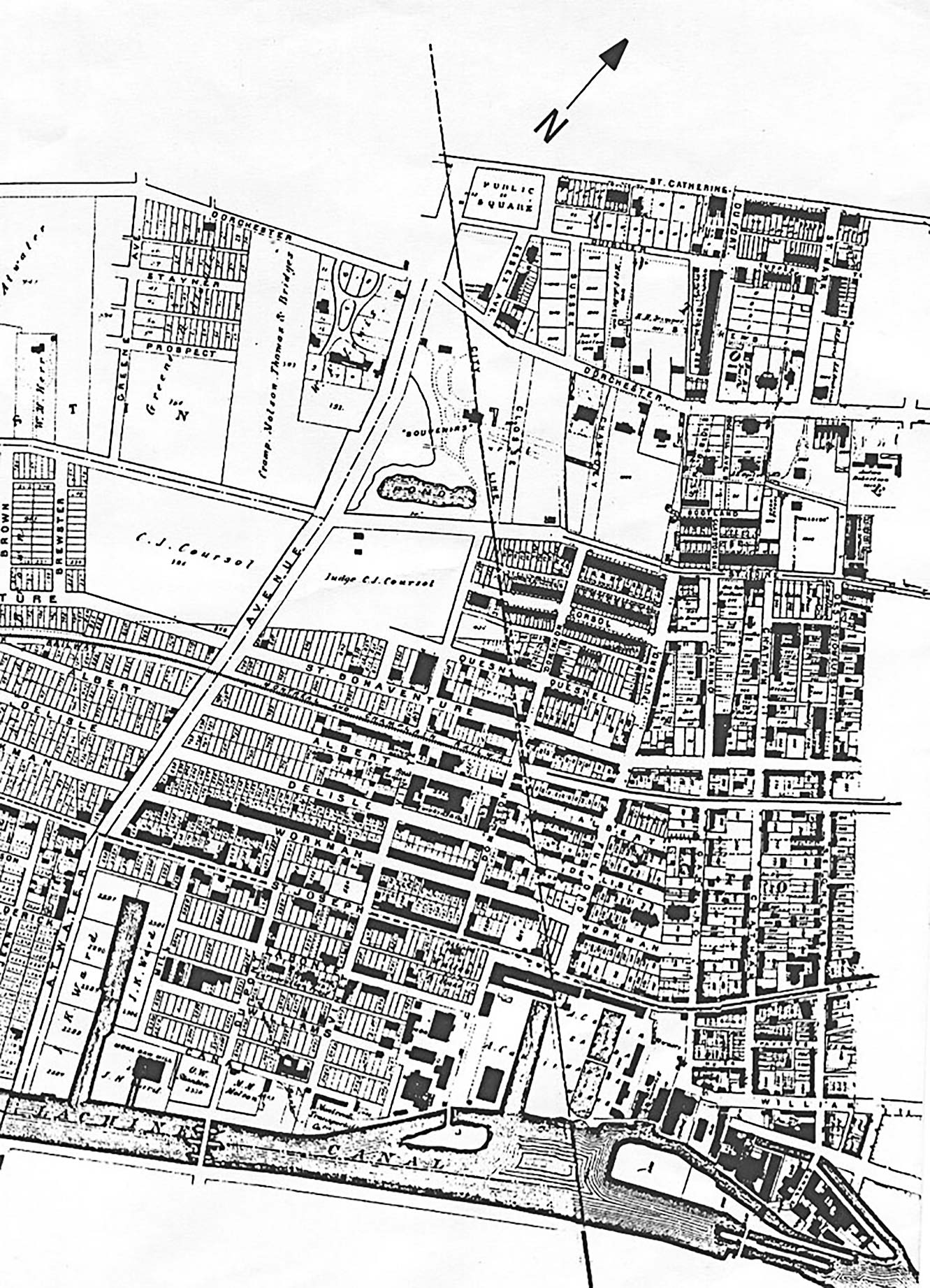

DJ Andy Williams on Montreal’s remarkable inter-war jazz age.

DJ, radio host and promoter, Andy Williams is a heavyweight on Montreal’s music scene. From 2002 to 2017, as one half of The Goods Sound System, he and partner Scott Clyke brought some of the world’s top DJs to their monthly dance parties at the Sala Rossa. Williams grew up in the U.K. but also spent part of his early life in New York and Toronto, as well as his mother’s native Jamaica. His tastes reflect the diversity of his background with influences that range from gospel to electro.

I asked Williams to contribute a story to Drift’s History Issue. He shared this article on how Montreal, through an influx of black immigrants from Nova Scotia, the United States and the Caribbean – along with the music they brought with them – became known, between the World Wars, as “Harlem of the North.”

“While working as an Educational Coordinator in the heart of the predominantly black ‘Little Burgundy’ community where this all took place, I met many veterans who got me inquisitive about the area’s history,” says Williams. His article presents a fascinating look at the meteoric rise of jazz in Little Burgundy; the surprising people who nurtured such international talents as pianist Oscar Peterson, tap dancer Ethel Bruneau and guitarist Nelson Symmonds; and the circumstances that would ultimately lead to the demise of Montreal’s jazz golden age.

Read Andy's article here.

Musicians would play regular jobs from 9 PM to one or two in the morning, and then search out the jazz clubs that used to stay open.

By pascale girardin photos by michel dubreuil

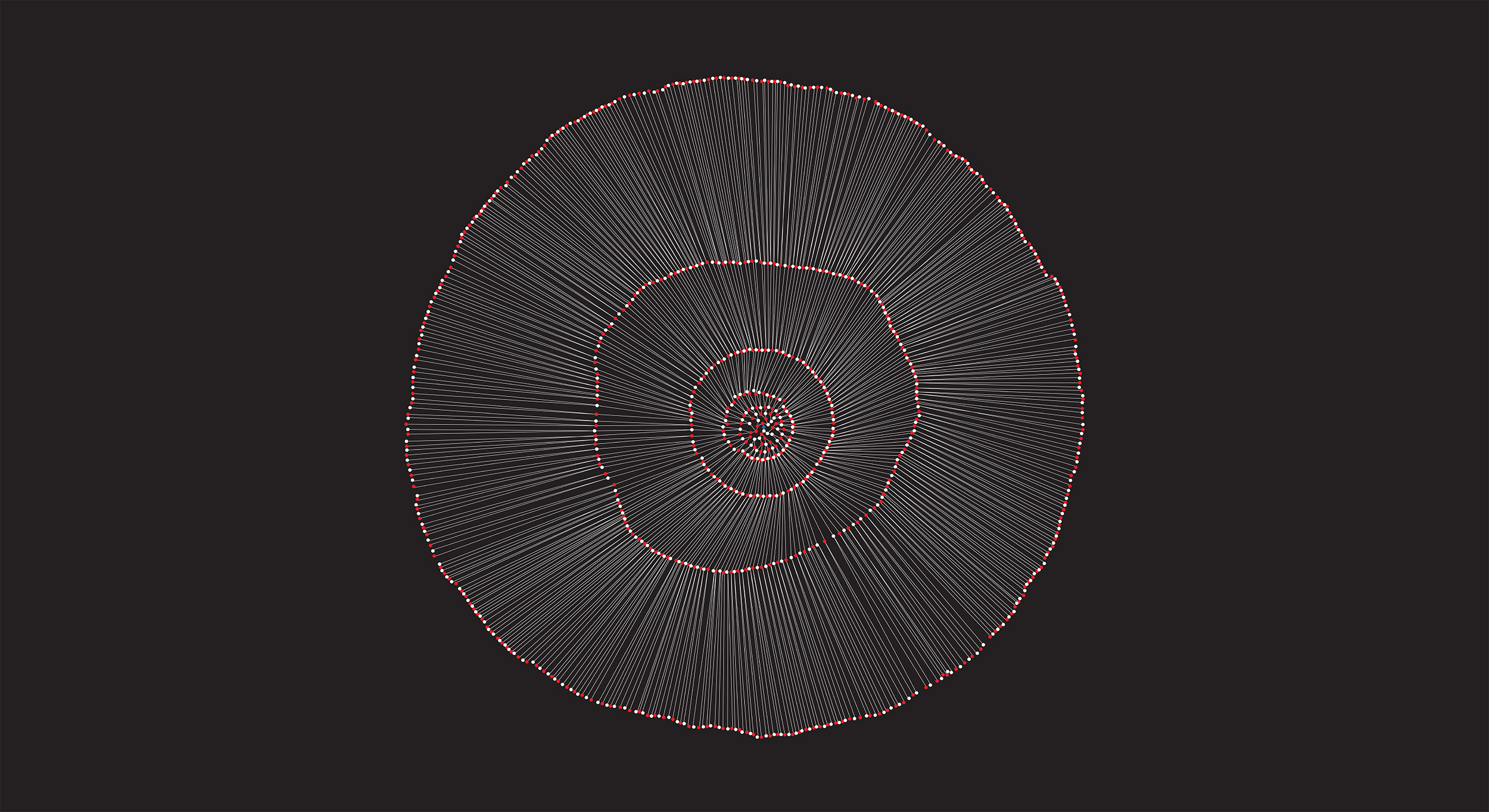

A sculpture tracing 10 generations reveals the complexity of ancestry.

In 2011, I was invited, along with nine other artists from the Americas, to create an outdoor sculpture for the International Symposium of In-Situ Art. The theme was “legacy.” We were each allocated a site along the four kilometres of trails at Les Jardins du Précambrien in Val-David, Quebec. Mine was to be a very large glacial boulder.

My concept was to shroud the rock in a lineage pattern known as cognatic descent. Unlike the more common agnatic structure – otherwise known as the standard family tree that traces paternal branches – cognatic follows the origins of mothers as well as fathers. (Think of it as a web with you at the centre and your ancestors spreading out radially in all directions.)

Just imagine all the hopes and loves, successes and hardships of those two thousand lives. Imagine the stories our webs could tell!

Over two weeks, my team and I constructed the work, entitled “This is not a Tree,” using gray glazed ceramic disks for women and white for men, linked together by metal wires. They flowed from a central disk position at the top of the rock and the heart of the sculpture. In all, it took 2048 disks to represent the number of people who, in 10 generations, went into the making of one individual.

By displaying each ancestor as a circle of clay, we get a snapshot of the scale of our origins. But just imagine all the hopes and loves, successes and hardships of those two thousand lives. Imagine the stories our webs could tell!

Of all the comments I received on the sculpture, one stuck with me as the most poignant. It was from a friend who had been adopted as an infant. She told me that she always felt that a part of her was missing because she had never known her birth parents. But in seeing the true number of lives that had formed her own, she said she had found some peace.

by pascale girardin

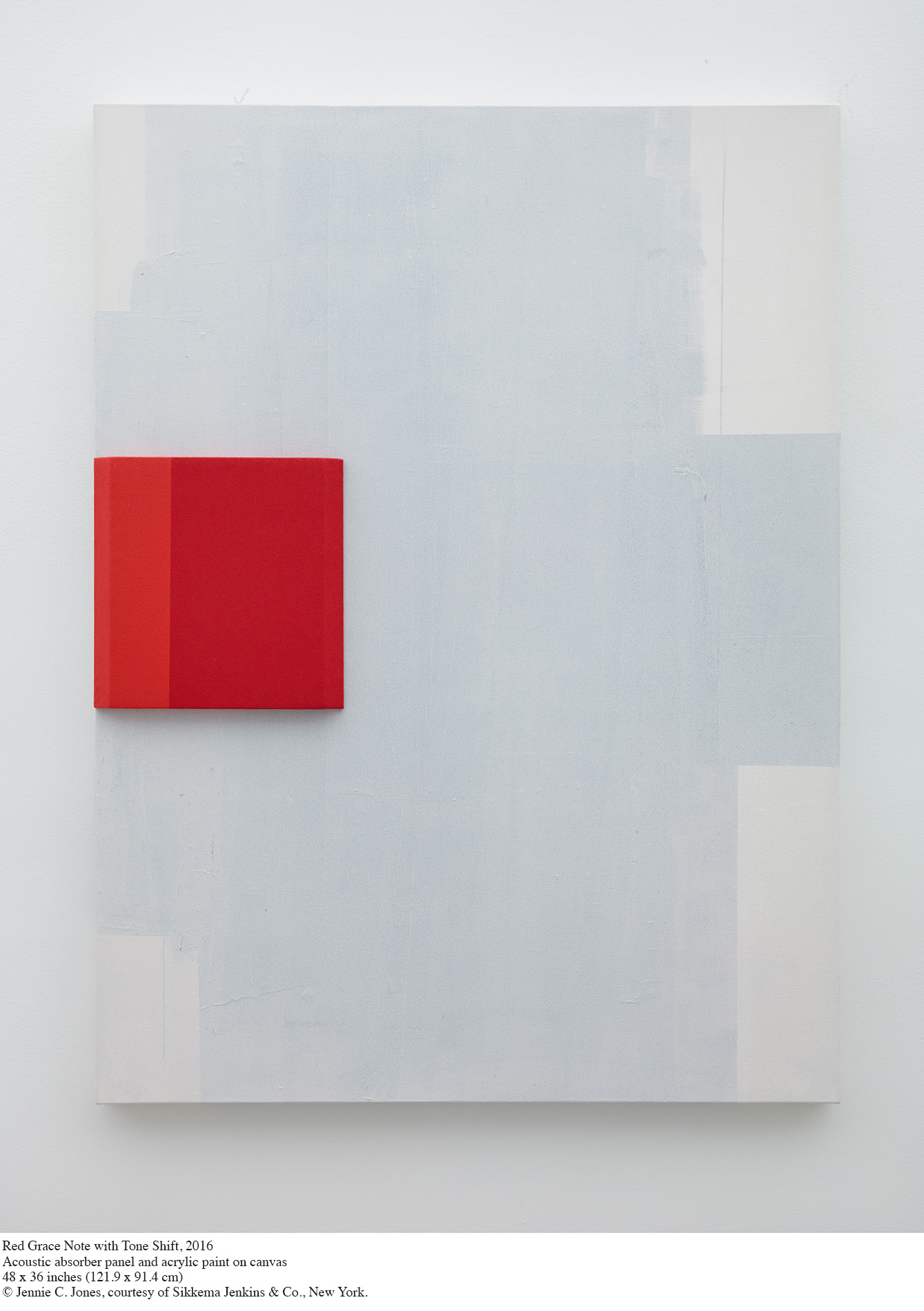

Jennie C. Jones: Compilation Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, 2015-16 Photo: Paul Hester Artwork © Jennie C. Jones, courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

Jennie C. Jones explores the language of experimental jazz through minimalism.

For me, one of the most exciting artists working to redress history today, is Jennie C. Jones. The artist from New York takes conceptual art – a genre overwhelmingly occupied by white male artists – and adopts its language to address the historical appropriation of jazz into academia and its absence within the canon of contemporary visual art. The result is that each piece reads like a puzzle: minimalist and austere in form; complex and politically charged in significance.

Her audio-visual explorations incorporate abstract paintings on acoustic panels, noise-cancelling instrument cables arranged as sculpture and sound clips spliced into sonic collage. The most moving is perhaps her piece entitled What a Little Moonlight (2007), in which a single note from Billie Holiday’s final performance in 1957 at the Newport Jazz Festival (predating Jones’ piece by exactly 50 years) is looped to produce a haunting, hypnotic lament.

There is a poetic nature to minimalism that is about striking a balance between full and empty… A single extended note could have a weight and simultaneous lightness. Something being busy or crowded does not make it more fulfilling to me.

As Jones told the Huffington Post, “There is a poetic nature to minimalism that is about striking a balance between full and empty… A single extended note could have a weight and simultaneous lightness. Something being busy or crowded does not make it more fulfilling to me.”

Jones explained her desire to use modernism as a means to comment on the African-American musical experience like this: “I would not say [they are] at odds, I hope that my work can point out the parallel relationships between the ‘social practices’ of black music at mid-century (and beyond) as well as its overt connection to dominant visual ‘isms’ historically. What’s more that it presents a place for that discourse to expand.”

The works of Jennie C. Jones are much more than meets the eye (and ear). With so little signal coming from them, they demand that you pay attention.

by pascale girardin photos by stephany hildebrand

Malika Tirolien on Montreal as a modern jazz city.

Montreal’s current jazz scene is perhaps most associated with the Montreal International Jazz Festival (June 28 to July 7), now in its 38th year. And while today’s event, which represents over 3,000 artists from more than 30 countries, covers a diverse array of musical genres, one regular performer who stays true to its original mandate as a jazz showcase is local talent Malika Tirolien. The Guadeloupe-born singer-songwriter is prolific in her work as a soloist, as well as with the improve group Kalmunity Vibe Collective and bands like New York-based Snarky Puppy and its offshoot Bokanté, which means “exchange” in Creole. Her music is heavily steeped in French-Caribbean music and traditional jazz. Here she describes Montreal’s modern jazz scene and where it’s headed.

In Montreal, people can create while being relaxed compared to other cities like Paris and New York where the hustle is nonstop

Pascale Girardin: I’ve been learning about Montreal’s jazz history in Little Burgundy, through my interview with Andy Williams of The Goods Sound System and was wondering if you are familiar with that period and if you see aspects of its legacy in the current jazz scene?

Malika Tirolien: I actually heard about it recently thanks to one of my best friends. Apparently, Little Burgundy saw the rise and golden days of Montreal’s jazz scene between the ’20s and ’50s. I heard there was a particular club called Rockhead’s Paradise, owned and founded by Rufus Rockhead that was the place to be at the time.

I think the legacy of this era is quite big since it shaped the future of jazz music in Montreal until today. Because of Little Burgundy, people like Rouè-Doudou Boicel, owner of the Rising Sun Jazz Club, who created the original Montreal Jazz Festival (called The Festijazz) in the late 1970s, and music promoter Charles Biddle who also created jazz festivals in the city in the early ’80s, got inspired and re-implanted the genre in Montreal. The Montreal Jazz Festival and the jazz clubs that we know now wouldn’t exist without these pioneers.

PG: What do you like about Montreal as a base for your music?

MT: I like the diversity of the music in Montreal. It reflects the diversity of the people that live here. There are so many cultures creating music that it’s becoming more and more difficult to put them all in one box. I am a part of the Kalmunity Vibe Collective, the biggest collective of artists in Canada. It is celebrating 15 years of improvising in Montreal through its two weekly events at Petit Campus and Resonance Café (my favorite jazz place with vegan treats).

PG: How would you compare Montreal’s modern jazz scene to other centres?

MT: It is really rich but also really mellow. In Montreal, people can create while being relaxed compared to other cities like Paris and New York where the hustle is nonstop. The only thing that I find very disappointing in Montreal is the fact that its huge musical community, full of talents of all horizons, are not all represented in the mainstream media. It is time for Montreal and the province of Quebec in general to acknowledge its diversity in all domains and give space and recognition to all types of Quebecois artists.

PG: What is your hope for the future of jazz in Montreal?

MT: To see it represented by people of different cultures. I want to hear more Caribbean jazz, Latin jazz, Ethiopian jazz, hip hop jazz, et cetera. I’d also like more clubs to open and maybe see another golden era of Montreal jazz!

Malika kalmunity Café resonance Snarky puppy