N° 7

Creativity

March 2019

by pascale girardin image by Geneviève Lebleu Watch video here

In a career spent building works of art for luxury environments, I have forged remarkable relationships with great minds in architecture, construction, hospitality, restauration and retail.

Though we come from diverse fields, we share a desire to create extraordinary spaces. Our common ground is that we are all moved by beauty, awed by craftsmanship, energized by the unexpected. In short, art is what makes us thrive.

Recently, I discussed my professional collaborations in an Adopt Inc. and Quebec Research Fund forum on the relationship between artistic expression and entrepreneurialism. Gatherings like this, as well the now internationally known C2 Montreal business conference, demonstrate that creativity isn’t exclusively the domain of creatives. As enterprises adapt to the speed of digital change, thinking creatively has become a workplace essential. The same is true for personal wellbeing. We’re seeing the impulse to create reflected in a renewed interest in the tactile arts—knitting circles, pottery clubs, sketching groups. They balance our dual need to reconnect and to disconnect. (You can’t touch your phone with muddy hands, after all.)

This issue, I share stories about my sources of creativity: the glaze formulas that I follow but leave open to possibility (“True Colours”); the personal projects undertaken by my studio staff (“Mixed Media”); the artists reimagining centuries-old Talavera ceramics (“Once Upon a Time in Mexico”); and the podcasts that inspire me (“Radio Redux”), among them.

“Drift” is my way of explaining how meandering thoughts can crystallize into a fully formed idea. It’s the origin of creative thinking and my mantra for daily life.

I invite you to drift with me.

Pascale Girardin

Our common ground is that we are all moved by beauty, awed by craftsmanship, energized by the unexpected. In short, art is what makes us thrive.

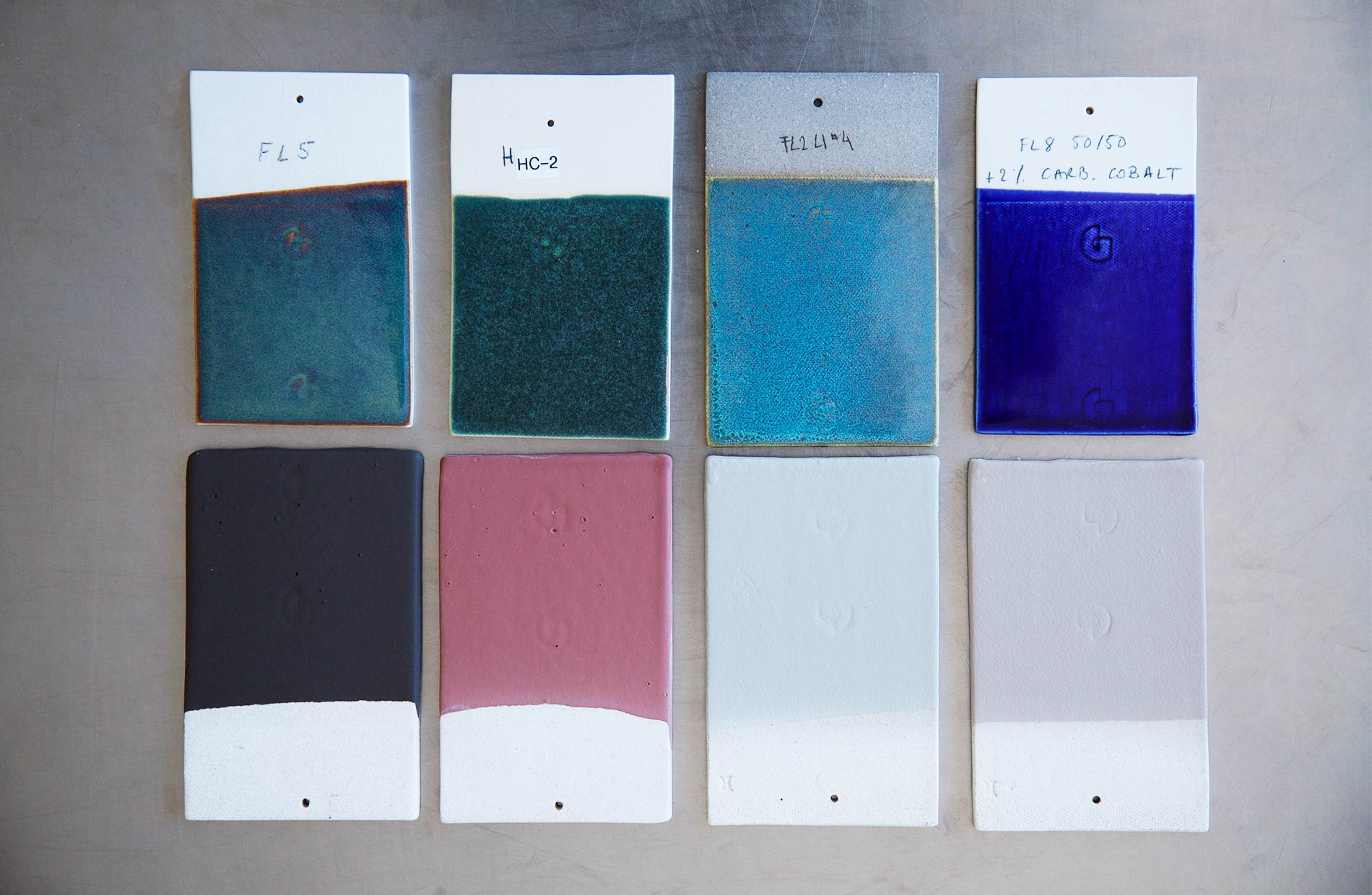

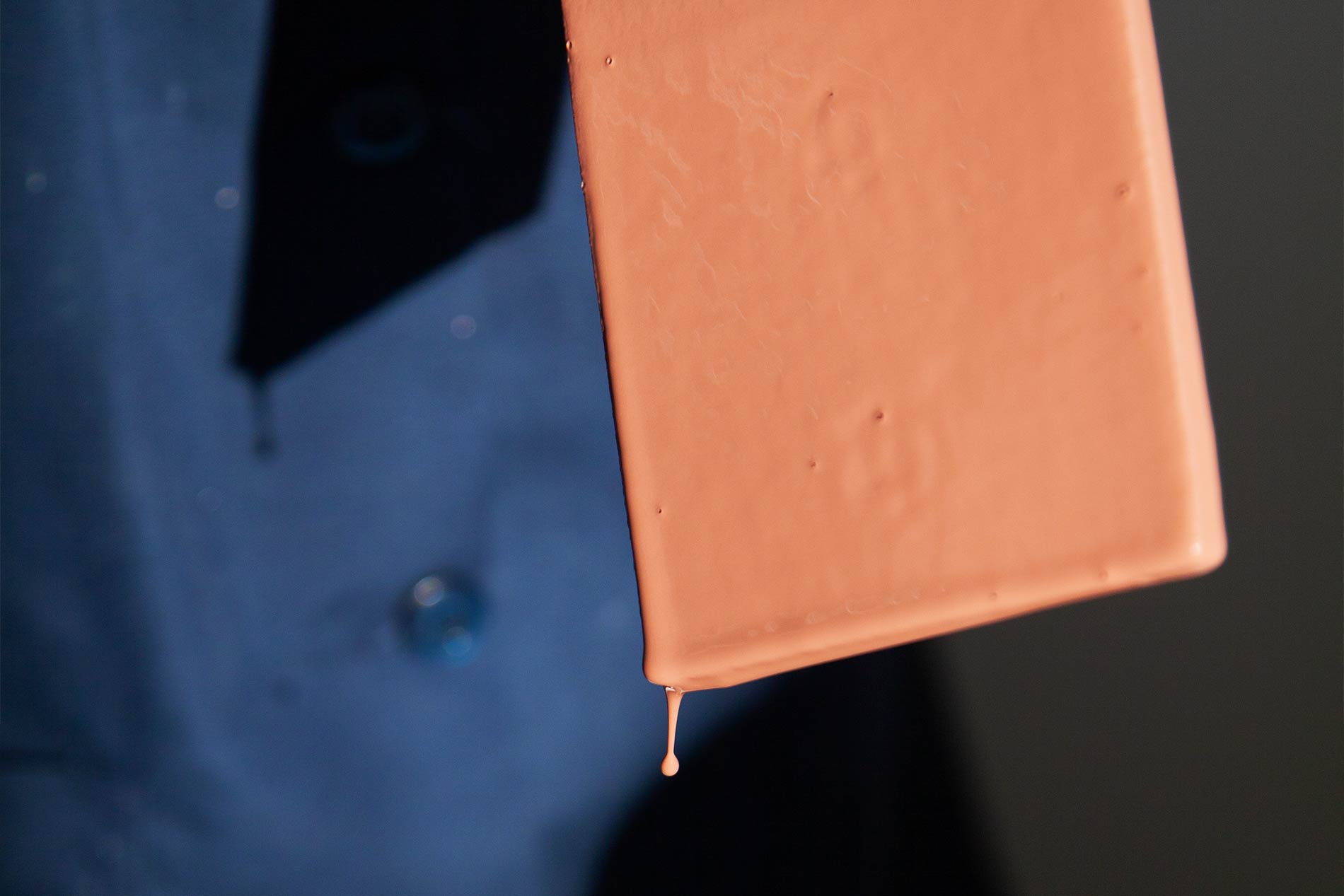

by pascale girardin photos by stephany hildebrand

Glazing is a lesson in how formulas can only take us so far.

Every time the kiln door opens, I take a deep breath. Inside, I may find pieces that have stood up to the 1,200-degree temperatures and myriad of other climactic, chemical and environmental variables. I may also find uninvited results. Nowhere is that truer than when it comes to glazes.

Glaze constituents can be summarized by four main ingredients: silica, which produces the glass coating; clay, that ensures a good adhesion to the ceramic body; flux, which brings down the melting point of the ingredients within the glaze; and metals and oxides, that combine to produce variations in colour, opacity and surface texture.

Glaze formulas are as precious as a chef’s recipe book. Three years ago, I worked with specialist Annie-Cecile Tremblay to develop a compendium of formulas that would become my colour palette. But here’s the tricky part: Unlike a time-tested food recipe, a ceramic glaze never replicates exactly the same way from one firing to the next—and the glazes I like tend to be the most problematic! A colour might look mint-green on the piece but turns beige in the kiln, or it could work well on a flat tile, but it pools at the base of a bowl. Sometimes even small chemical changes to the city’s water supply, mixed into my batches, can affect the end result. You just never know what you’ll get until the firing.

That uncertainty isn’t something to fear. It’s what makes my work interesting. I operate by the book, but I keep an open mind to possibility. I find that as often as I am confronted with unexpected outcomes, I am also pleasantly rewarded. I learn, I correct, I shift my approach to account for the new results. And sometimes I try to replicate that one beautiful mistake that changed everything.

I find that as often as I am confronted with unexpected outcomes, I am also pleasantly rewarded.

by pascale girardin illustrations by wolfe girardin

Three podcasts that think differently.

The last decade has introduced an excess of entertainment. We binge-watch long-form TV, flutter between social channels and pick up personalized news on demand. But in the midst of all this new media, one old-school platform is also having its day: Radio.

I am a podcast junkie. Having my hands in the clay leaves my mind free to roam, which is why I and so many of my fellow potters are such big podcast fans. Here are three shows in my playlist right now. Their clever and unorthodox storytelling always takes me down new and unexpected lines of thought.

Radiolab

The tagline “Investigating a strange world” provides a succinct summary of the bizarre meeting of minds that is the conversation between composer Jad Abumrad and science writer Robert Krulwich. Since 2002, they have been explaining big ideas in the simplest—and yet most mind-blowing—terms, whether the topic is gene-swapping or the dark side of human nature.

Click here for more.

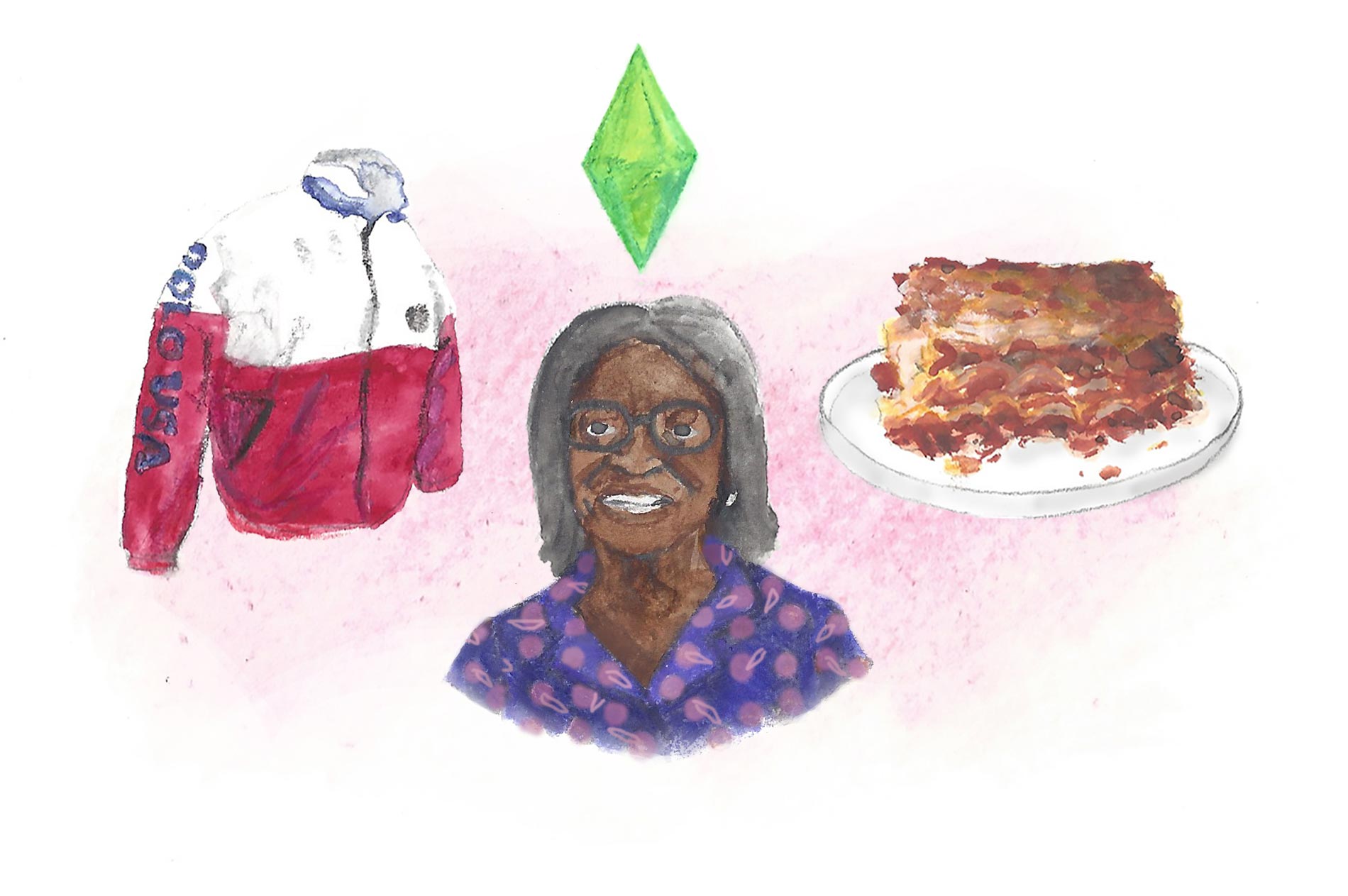

The Nod

Its title refers to the subtle understanding that exists between two people of colour in a white-dominated environment. But, no matter what your shade, there is much to learn from co-hosts Brittany Luse and Eric Eddings as they explore under-the-radar stories about being black, such as eating lasagna the Ethiopian way and Josephine Baker’s attempt to build a racial utopia.

Click here for more.

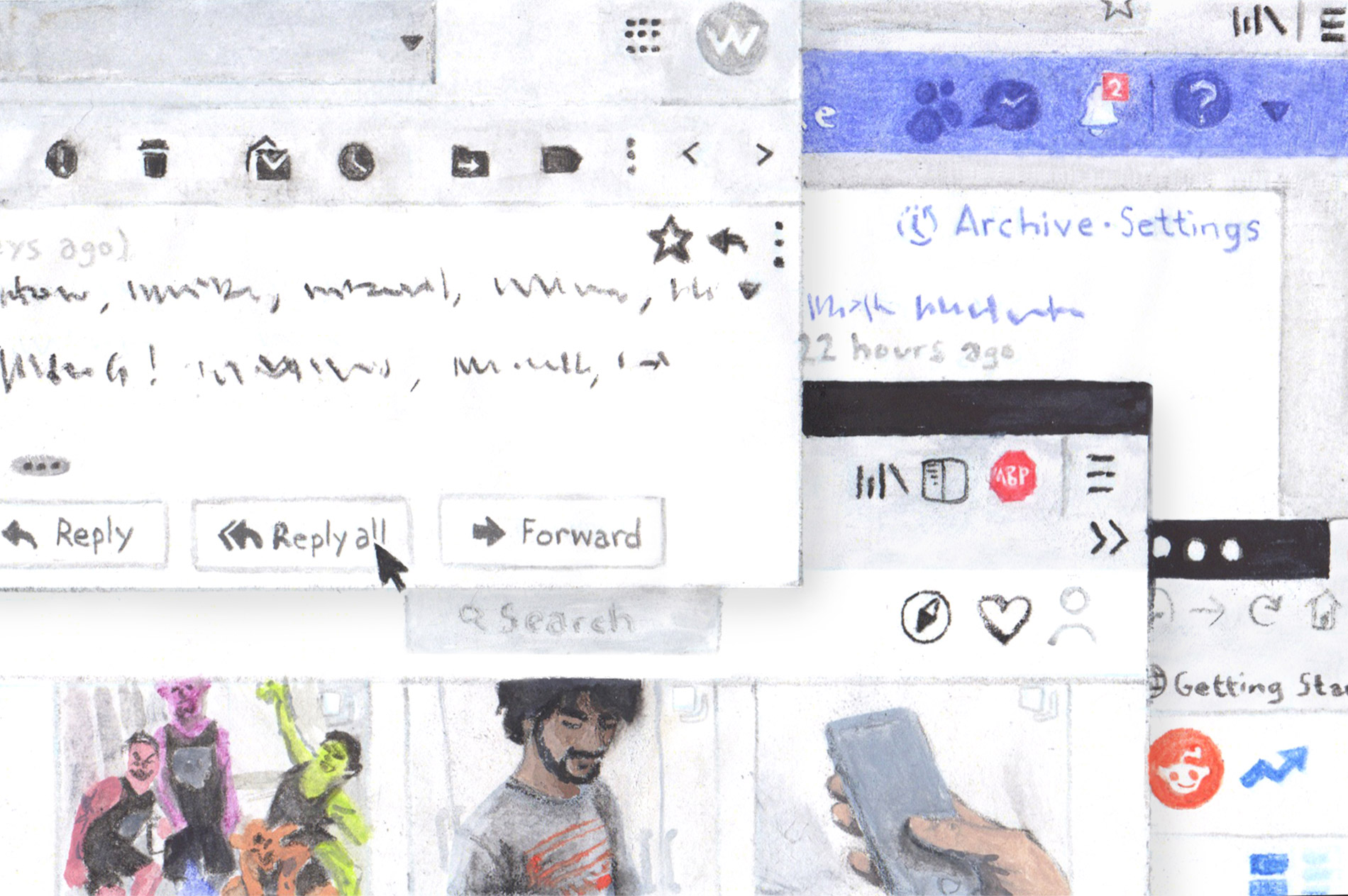

Reply All

The podcast dubbed “a survival guide for modern life,” focuses on the internet and social media: how they affect us, how we affect them. Lovable-nerd hosts PJ Vogt and Alex Goldman look into subjects such as viral conspiracies, online scams and the internet’s shadowy underbelly, with every story set to a gorgeous soundscape, that, taken alone, is reason enough to listen.

Click here for more.

by pascale Girardin photos by pascale girardin

International artists are breathing new life into traditional Talavera pottery.

The distinct blue-and-ochre-yellow tiles that adorn cathedrals, fountains and courtyards across the Spanish-speaking world originated in the middle ages in the town of Talavera de la Reina, just outside Toledo, Spain. The Spanish introduced the technique to Mexico. And since colonial times, the region of Puebla has assumed the mantle of this ceramic tradition.

Two summers ago, I had the opportunity to visit the Pueblan city of Cholula, where the supply of high-quality local clay has made it a centre for pottery for nearly four centuries. Talavera, which extends beyond tiles to vases, tableware and sculpture, has well-defined standards. Use of colouring, applied by hand over its traditional white tin-glaze, is limited to locally mined oxides and these include cobalt for blues, iron ochre for yellows, copper oxide for greens and manganese for mauves.

Today, sadly, knock-offs abound, which has undermined the laborious craftsmanship of the region’s genuine Talavera manufacturers.

On my travels, however, I was delighted to discover a new crop of artists who not only operate within the traditional rules, but who are also bringing the practice into the 21st century. At the forefront of this movement is Angelica Moreno, whose studio Talavera de la Reyna, gives the pottery contemporary styling (think colour-blocked crockery and minimalist lamp bases) and whose brand extends to a chic boutique hotel, a restaurant and a line of organic jams. Most notably, Moreno works tirelessly to educate prospective buyers and to ensure designation-of-origin certification for Puebla’s Talavera.

Over the years, Moreno has invited more than 70 artists to her studio to reimagine the technique. Their works, showcased as part of her Alarca Gallery, range from Mexican artist Betsabeé Romero’s handpainted tiled-car sculpture to a ceramic homage to Paul McCarthy’s infamously erotic “Tree” monument. Moreno’s efforts are striking examples of how an age-old concept can take on new relevance with a little creative thinking.

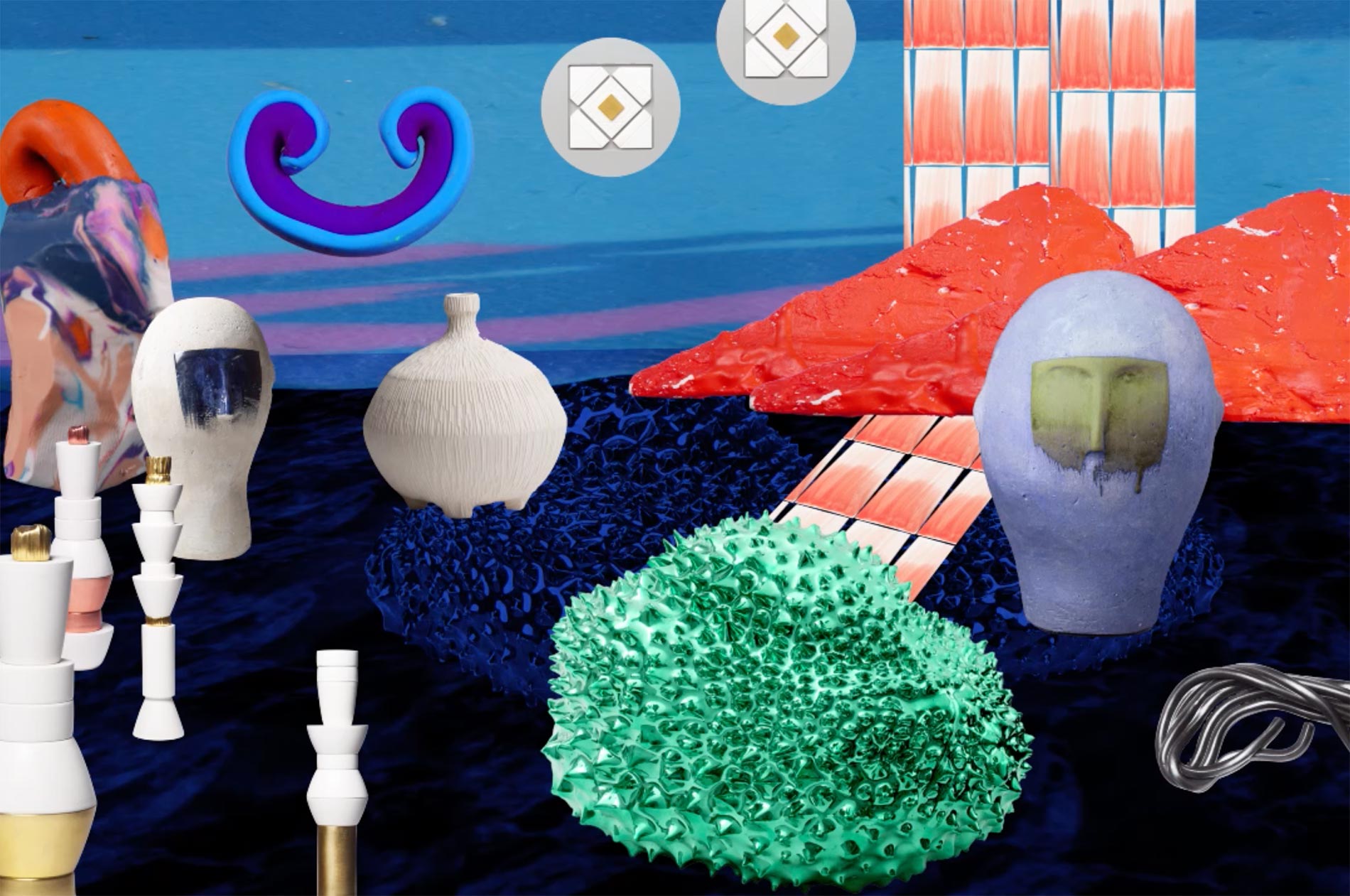

by pascale Girardin sculpture by wolfe girardin photos by stephany hildebrand

From photography to knitwear, my studio team have creativity all stitched up.

When I have a client project in the works, I rely on my team of in-house experts to help produce the hundreds, or even thousands, of pieces that go into each installation, not to mention the logistics of getting those pieces to their destination and in place on time. Each team member brings an artistic skillset to the job, talents honed from running their own impressive ateliers. Here, they describe those personal projects in their own words.

Project manager

An industrial designer by training, Maud Beauchamp is well acquainted with turning 2D models into 3D realities. “I embrace a multidisciplinary, intuitive and spontaneous approach to design,” she says. As one half of the studio mpgmb with long-time friend Marie-Pier Guilmain, she applies the geometric visual language of the digital world and transforms it into colourful, tactile furniture and décor in ceramics, wood, marble, steel and textiles.

Click here for more.

Studio assistant

Whether she is combining street art with ceramics or mixing medieval motifs with iconography from pop culture and the occult, Ms. Teri treats each irreverent mash-up as a visual diary of her experiences. “My work is about ritualistic craftsmanship,” she says. “These personal chronicles of urban life and spirituality transcend medium and genre.”

Click here for more.

Project coordinator

In September, Jean-Philippe Cliche and his friend Rémy Savard launched a YouTube channel devoted to their shared passion for knitting. Episodes of Les SHEEPendales cover tricks, techniques and materials, and the pair also conducts interviews with textile artists. Cliche describes his “desire to produce beautiful pieces at a human speed” as the impetus for his own line, Atelier Cliché: “Row-by-row, I create handmade knitwear using 100-percent natural and recycled fibres in styles that have staying power. It’s what you’d call ‘slow fashion.’”

Click here for more.

Studio assistant

A recent graduate of Concordia University, Wolfe Girardin may be a millennial himself but his work casts a critical eye on his generation’s main mode of communication: social media. By recreating Snapchat and Instagram story screenshots as charcoal drawings, he sheds light on the psycho-social issues stemming from smartphone use. “It’s a beginning,” he says. “This year I have been writing poetry, composing music and working on videos that address similar themes.” Find Girardin’s drawings on display at this year’s Chromatic Festival in Montreal, May 10 to 17.

Click here for more.

Photographer

A self-taught photographer, Stephany Hildebrand has tackled many subjects in her short-but-prolific career, from architecture to social rapportage. Most recently Hildebrand has turned her lens to the natural world. “I grew up in a small town surrounded by fields and forests, which I spent my childhood exploring in solitude,” she says. Two of Hildebrand’s current photo projects include the environmental landscape series Rhapsody in Green and the still-life collection Elle aime les fleurs in collaboration with Montreal florist Isabelle Seguin. She credits her early exposure to nature, as well as these immersive works, for her decision to go back to school in Environmental Technology.

Click here for more.

by pascale Girardin Sketches by pascale girardin

By studying process, we find our results.

Sculpture Practice: Handbuilding is the name of a course I teach to second-year ceramics students at the Université de Québec à Montréal. The idea is that a finished piece of art is part of a creative continuum that we can view as the punctuation mark—the question, exclamation or full stop—on the longer story that is the process.

One of the students’ pivotal assignments is to keep a logbook. This reflective tool provides a record of what’s going on in their minds as they create. They can make sketches, talk about an artist whose work they admire or comment on how to adjust their glaze for the next try. There are no rules; no good notes or bad notes. The only requirements are to examine their motivations and to be present to the process of artmaking.

I adapted this course from my own process. Ceramics requires detailed notetaking to track variables such as firing temperatures, kiln placement and glaze formulas (see “True Colours” for an example). The logbook works in tandem with these notes, letting students develop an awareness for how a piece is evolving, not just technically but thematically.

To grade the students, I look for coherence. A piece that cracks or warps in the kiln is not necessarily poorly marked if it’s in line with the observations made, the effort put in and the lessons learned.

In time, students learn to see overarching themes in their logbooks, where they once saw only seemingly unconnected ideas.. With practice, they’ll learn to look at their finished pieces and instinctively read the story written there.

A piece that cracks or warps in the kiln is not necessarily poorly marked if it’s in line with the observations made, the effort put in and the lessons learned.