Ideas and inspirations

from the studio

of Pascale Girardin

N° 7

Creativity

March 2019

by pascale girardin image by Geneviève Lebleu Watch video here

In a career spent building works of art for luxury environments, I have forged remarkable relationships with great minds in architecture, construction, hospitality, restauration and retail.

Though we come from diverse fields, we share a desire to create extraordinary spaces. Our common ground is that we are all moved by beauty, awed by craftsmanship, energized by the unexpected. In short, art is what makes us thrive.

Recently, I discussed my professional collaborations in an Adopt Inc. and Quebec Research Fund forum on the relationship between artistic expression and entrepreneurialism. Gatherings like this, as well the now internationally known C2 Montreal business conference, demonstrate that creativity isn’t exclusively the domain of creatives. As enterprises adapt to the speed of digital change, thinking creatively has become a workplace essential. The same is true for personal wellbeing. We’re seeing the impulse to create reflected in a renewed interest in the tactile arts—knitting circles, pottery clubs, sketching groups. They balance our dual need to reconnect and to disconnect. (You can’t touch your phone with muddy hands, after all.)

This issue, I share stories about my sources of creativity: the glaze formulas that I follow but leave open to possibility (“True Colours”); the personal projects undertaken by my studio staff (“Mixed Media”); the artists reimagining centuries-old Talavera ceramics (“Once Upon a Time in Mexico”); and the podcasts that inspire me (“Radio Redux”), among them.

“Drift” is my way of explaining how meandering thoughts can crystallize into a fully formed idea. It’s the origin of creative thinking and my mantra for daily life.

I invite you to drift with me.

Pascale Girardin

Our common ground is that we are all moved by beauty, awed by craftsmanship, energized by the unexpected. In short, art is what makes us thrive.

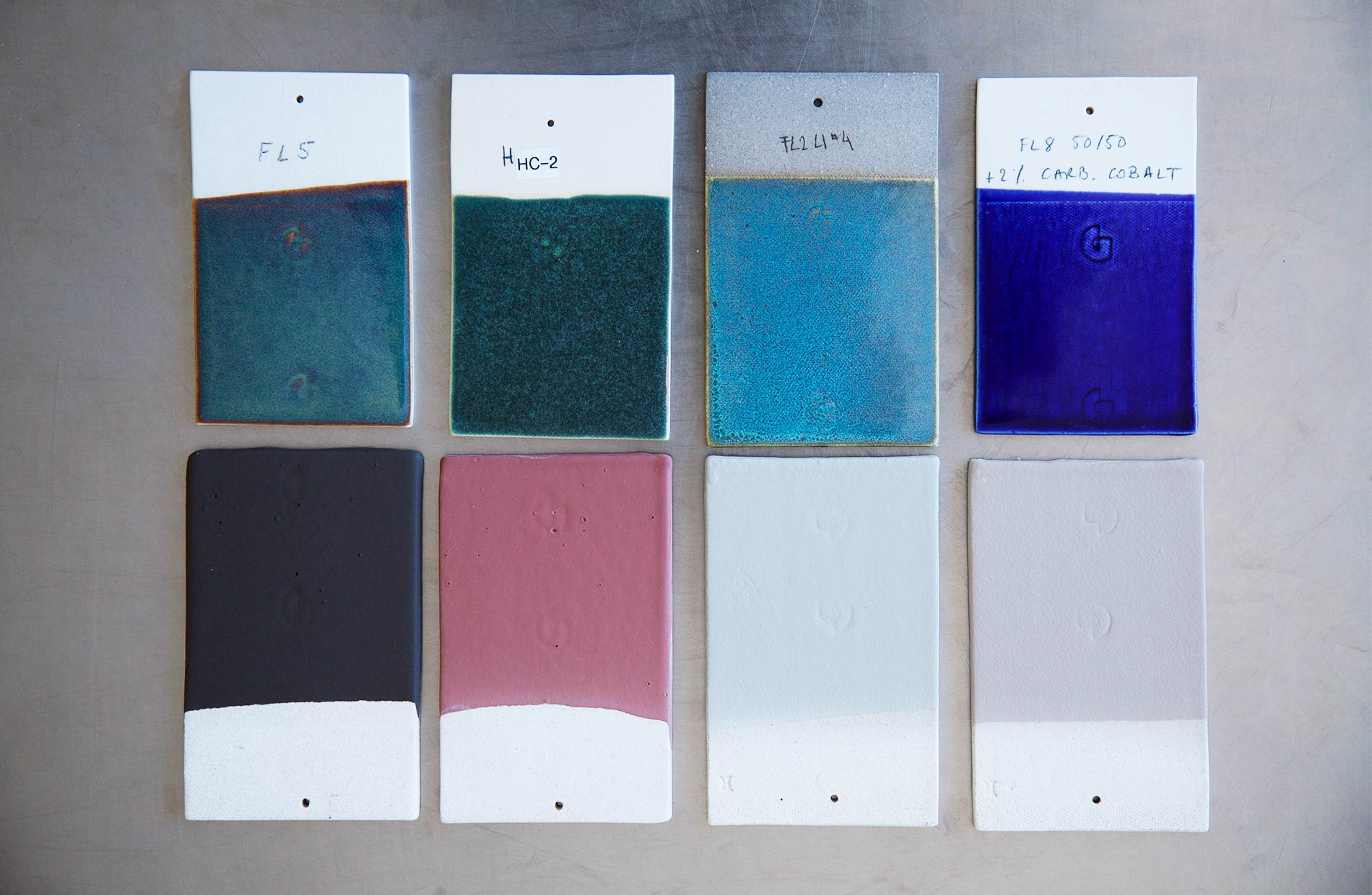

by pascale girardin photos by stephany hildebrand

Glazing is a lesson in how formulas can only take us so far.

Every time the kiln door opens, I take a deep breath. Inside, I may find pieces that have stood up to the 1,200-degree temperatures and myriad of other climactic, chemical and environmental variables. I may also find uninvited results. Nowhere is that truer than when it comes to glazes.

Glaze constituents can be summarized by four main ingredients: silica, which produces the glass coating; clay, that ensures a good adhesion to the ceramic body; flux, which brings down the melting point of the ingredients within the glaze; and metals and oxides, that combine to produce variations in colour, opacity and surface texture.

Glaze formulas are as precious as a chef’s recipe book. Three years ago, I worked with specialist Annie-Cecile Tremblay to develop a compendium of formulas that would become my colour palette. But here’s the tricky part: Unlike a time-tested food recipe, a ceramic glaze never replicates exactly the same way from one firing to the next—and the glazes I like tend to be the most problematic! A colour might look mint-green on the piece but turns beige in the kiln, or it could work well on a flat tile, but it pools at the base of a bowl. Sometimes even small chemical changes to the city’s water supply, mixed into my batches, can affect the end result. You just never know what you’ll get until the firing.

That uncertainty isn’t something to fear. It’s what makes my work interesting. I operate by the book, but I keep an open mind to possibility. I find that as often as I am confronted with unexpected outcomes, I am also pleasantly rewarded. I learn, I correct, I shift my approach to account for the new results. And sometimes I try to replicate that one beautiful mistake that changed everything.

I find that as often as I am confronted with unexpected outcomes, I am also pleasantly rewarded.

by pascale girardin illustrations by wolfe girardin

Three podcasts that think differently.

The last decade has introduced an excess of entertainment. We binge-watch long-form TV, flutter between social channels and pick up personalized news on demand. But in the midst of all this new media, one old-school platform is also having its day: Radio.

I am a podcast junkie. Having my hands in the clay leaves my mind free to roam, which is why I and so many of my fellow potters are such big podcast fans. Here are three shows in my playlist right now. Their clever and unorthodox storytelling always takes me down new and unexpected lines of thought.

Radiolab

The tagline “Investigating a strange world” provides a succinct summary of the bizarre meeting of minds that is the conversation between composer Jad Abumrad and science writer Robert Krulwich. Since 2002, they have been explaining big ideas in the simplest—and yet most mind-blowing—terms, whether the topic is gene-swapping or the dark side of human nature.

Click here for more.

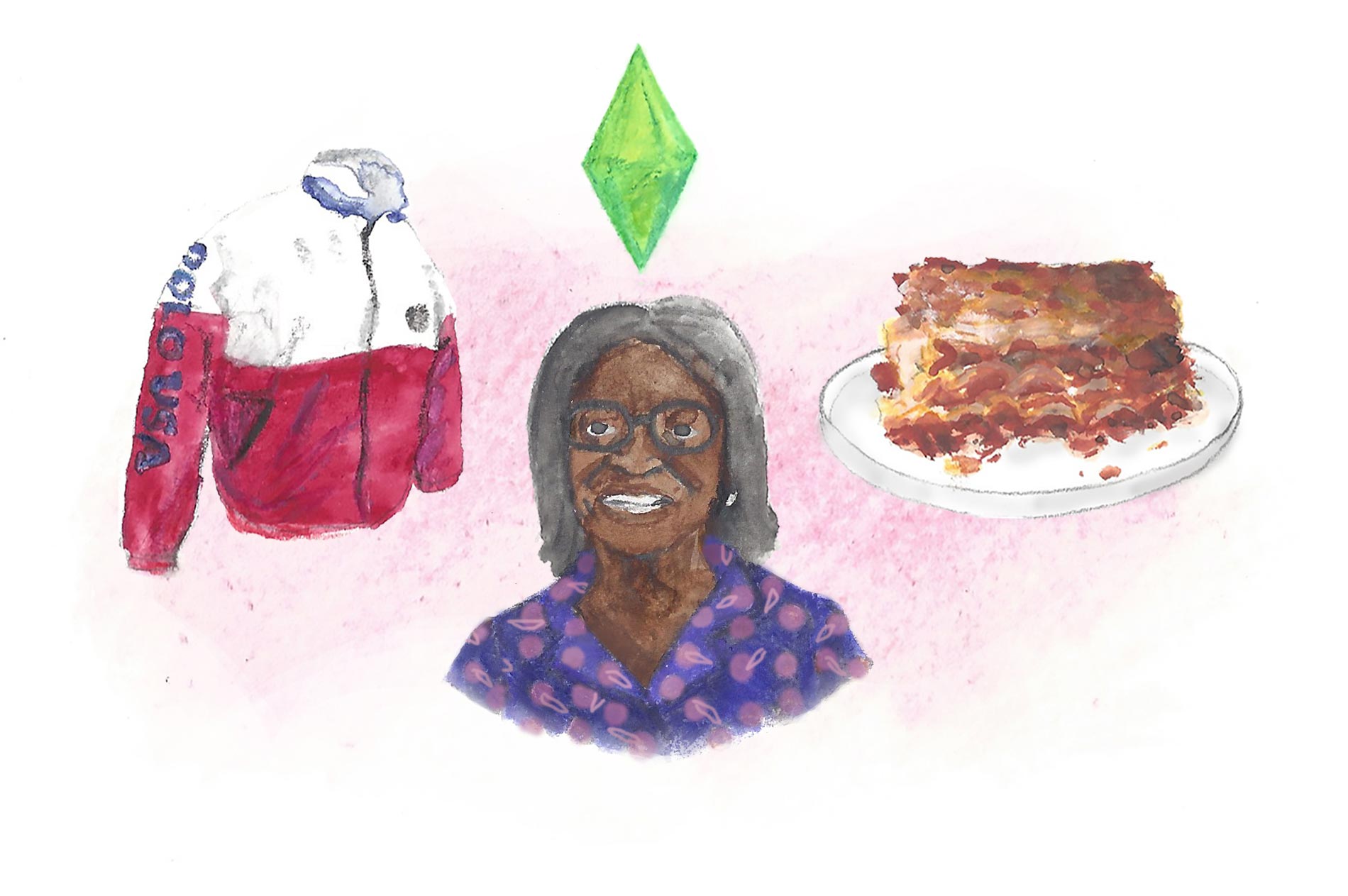

The Nod

Its title refers to the subtle understanding that exists between two people of colour in a white-dominated environment. But, no matter what your shade, there is much to learn from co-hosts Brittany Luse and Eric Eddings as they explore under-the-radar stories about being black, such as eating lasagna the Ethiopian way and Josephine Baker’s attempt to build a racial utopia.

Click here for more.

Reply All

The podcast dubbed “a survival guide for modern life,” focuses on the internet and social media: how they affect us, how we affect them. Lovable-nerd hosts PJ Vogt and Alex Goldman look into subjects such as viral conspiracies, online scams and the internet’s shadowy underbelly, with every story set to a gorgeous soundscape, that, taken alone, is reason enough to listen.

Click here for more.

by pascale Girardin photos by pascale girardin

International artists are breathing new life into traditional Talavera pottery.

The distinct blue-and-ochre-yellow tiles that adorn cathedrals, fountains and courtyards across the Spanish-speaking world originated in the middle ages in the town of Talavera de la Reina, just outside Toledo, Spain. The Spanish introduced the technique to Mexico. And since colonial times, the region of Puebla has assumed the mantle of this ceramic tradition.

Two summers ago, I had the opportunity to visit the Pueblan city of Cholula, where the supply of high-quality local clay has made it a centre for pottery for nearly four centuries. Talavera, which extends beyond tiles to vases, tableware and sculpture, has well-defined standards. Use of colouring, applied by hand over its traditional white tin-glaze, is limited to locally mined oxides and these include cobalt for blues, iron ochre for yellows, copper oxide for greens and manganese for mauves.

Today, sadly, knock-offs abound, which has undermined the laborious craftsmanship of the region’s genuine Talavera manufacturers.

On my travels, however, I was delighted to discover a new crop of artists who not only operate within the traditional rules, but who are also bringing the practice into the 21st century. At the forefront of this movement is Angelica Moreno, whose studio Talavera de la Reyna, gives the pottery contemporary styling (think colour-blocked crockery and minimalist lamp bases) and whose brand extends to a chic boutique hotel, a restaurant and a line of organic jams. Most notably, Moreno works tirelessly to educate prospective buyers and to ensure designation-of-origin certification for Puebla’s Talavera.

Over the years, Moreno has invited more than 70 artists to her studio to reimagine the technique. Their works, showcased as part of her Alarca Gallery, range from Mexican artist Betsabeé Romero’s handpainted tiled-car sculpture to a ceramic homage to Paul McCarthy’s infamously erotic “Tree” monument. Moreno’s efforts are striking examples of how an age-old concept can take on new relevance with a little creative thinking.

by pascale Girardin sculpture by wolfe girardin photos by stephany hildebrand

From photography to knitwear, my studio team have creativity all stitched up.

When I have a client project in the works, I rely on my team of in-house experts to help produce the hundreds, or even thousands, of pieces that go into each installation, not to mention the logistics of getting those pieces to their destination and in place on time. Each team member brings an artistic skillset to the job, talents honed from running their own impressive ateliers. Here, they describe those personal projects in their own words.

Project manager

An industrial designer by training, Maud Beauchamp is well acquainted with turning 2D models into 3D realities. “I embrace a multidisciplinary, intuitive and spontaneous approach to design,” she says. As one half of the studio mpgmb with long-time friend Marie-Pier Guilmain, she applies the geometric visual language of the digital world and transforms it into colourful, tactile furniture and décor in ceramics, wood, marble, steel and textiles.

Click here for more.

Studio assistant

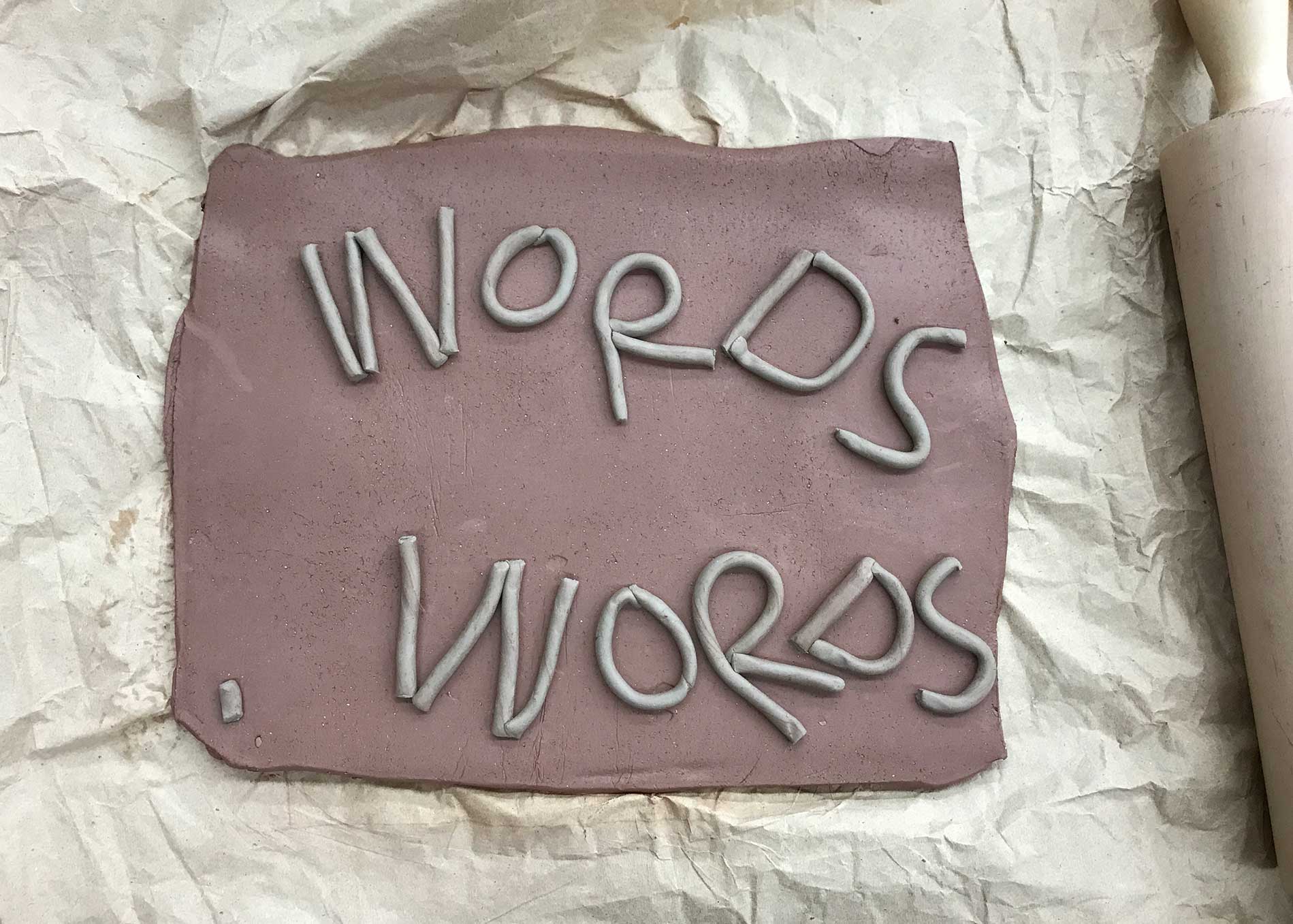

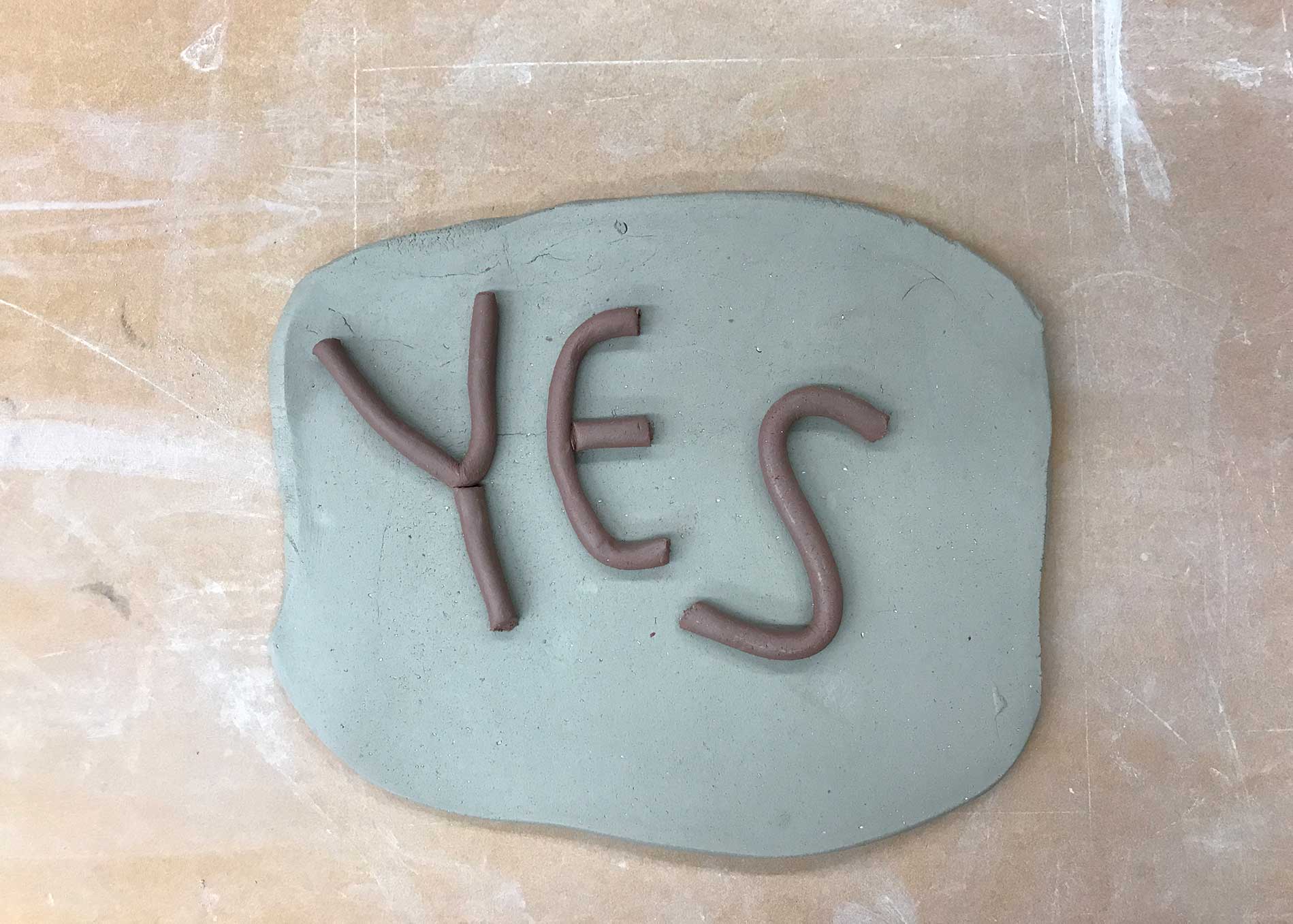

Whether she is combining street art with ceramics or mixing medieval motifs with iconography from pop culture and the occult, Ms. Teri treats each irreverent mash-up as a visual diary of her experiences. “My work is about ritualistic craftsmanship,” she says. “These personal chronicles of urban life and spirituality transcend medium and genre.”

Click here for more.

Project coordinator

In September, Jean-Philippe Cliche and his friend Rémy Savard launched a YouTube channel devoted to their shared passion for knitting. Episodes of Les SHEEPendales cover tricks, techniques and materials, and the pair also conducts interviews with textile artists. Cliche describes his “desire to produce beautiful pieces at a human speed” as the impetus for his own line, Atelier Cliché: “Row-by-row, I create handmade knitwear using 100-percent natural and recycled fibres in styles that have staying power. It’s what you’d call ‘slow fashion.’”

Click here for more.

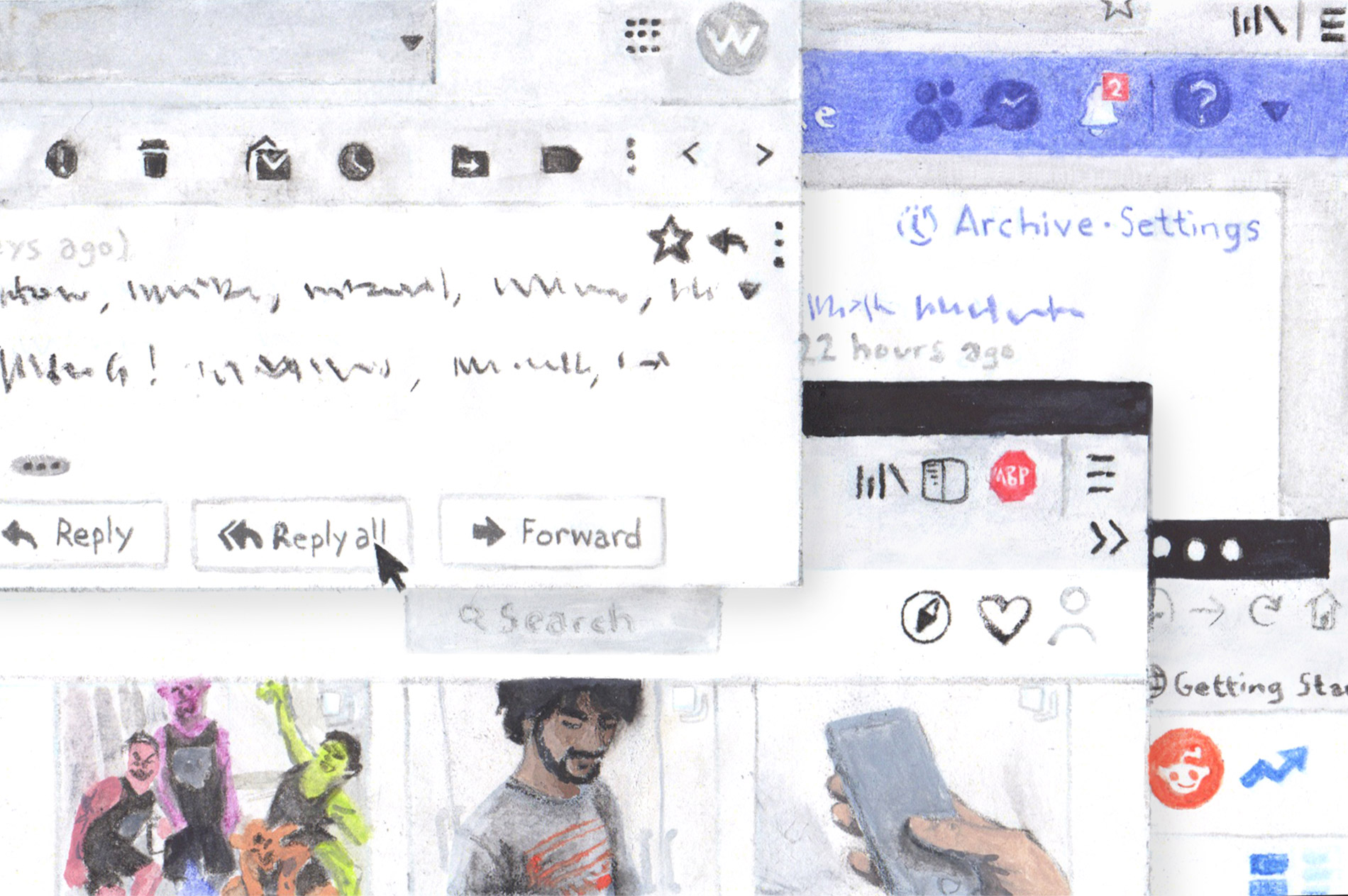

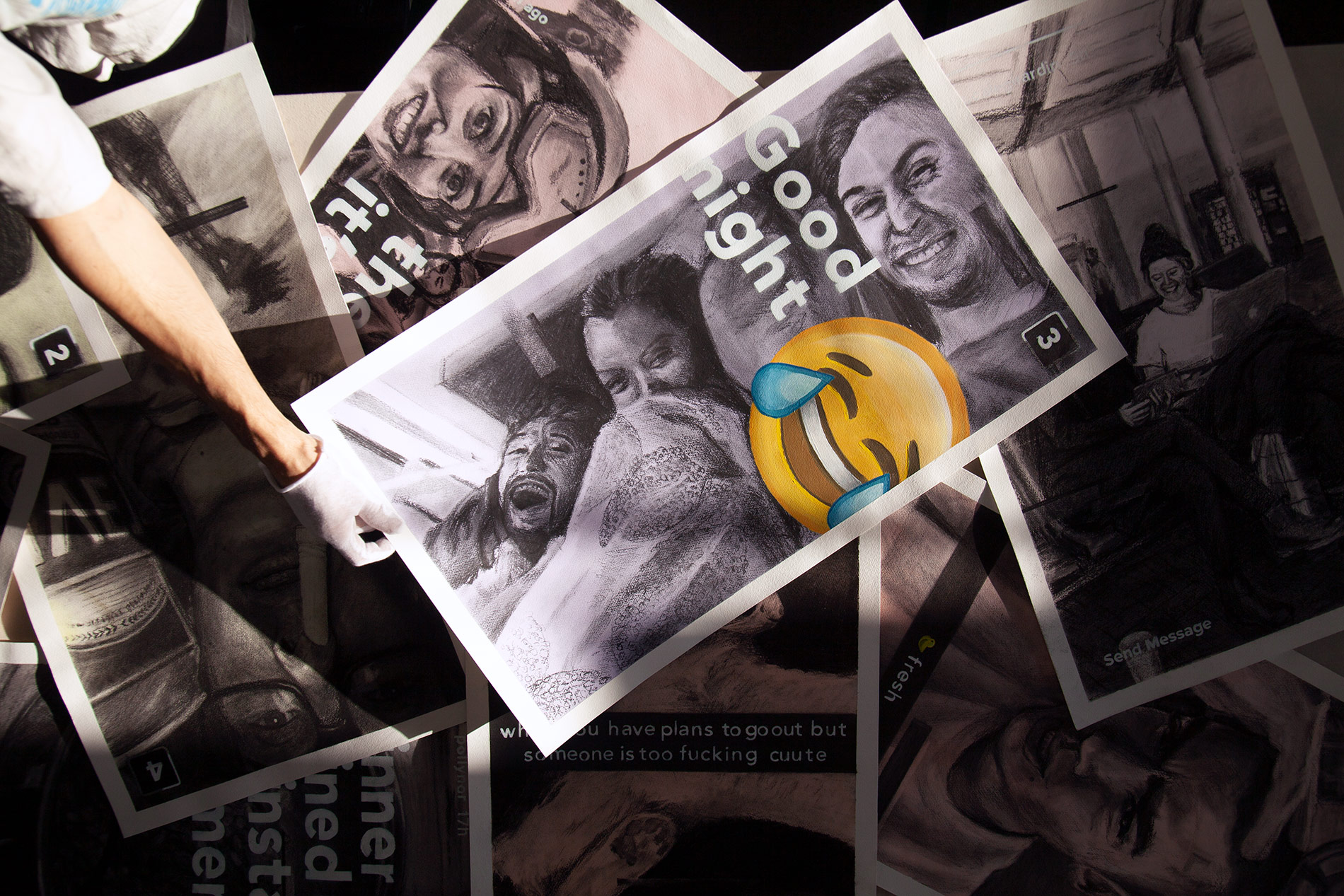

Studio assistant

A recent graduate of Concordia University, Wolfe Girardin may be a millennial himself but his work casts a critical eye on his generation’s main mode of communication: social media. By recreating Snapchat and Instagram story screenshots as charcoal drawings, he sheds light on the psycho-social issues stemming from smartphone use. “It’s a beginning,” he says. “This year I have been writing poetry, composing music and working on videos that address similar themes.” Find Girardin’s drawings on display at this year’s Chromatic Festival in Montreal, May 10 to 17.

Click here for more.

Photographer

A self-taught photographer, Stephany Hildebrand has tackled many subjects in her short-but-prolific career, from architecture to social rapportage. Most recently Hildebrand has turned her lens to the natural world. “I grew up in a small town surrounded by fields and forests, which I spent my childhood exploring in solitude,” she says. Two of Hildebrand’s current photo projects include the environmental landscape series Rhapsody in Green and the still-life collection Elle aime les fleurs in collaboration with Montreal florist Isabelle Seguin. She credits her early exposure to nature, as well as these immersive works, for her decision to go back to school in Environmental Technology.

Click here for more.

by pascale Girardin Sketches by pascale girardin

By studying process, we find our results.

Sculpture Practice: Handbuilding is the name of a course I teach to second-year ceramics students at the Université de Québec à Montréal. The idea is that a finished piece of art is part of a creative continuum that we can view as the punctuation mark—the question, exclamation or full stop—on the longer story that is the process.

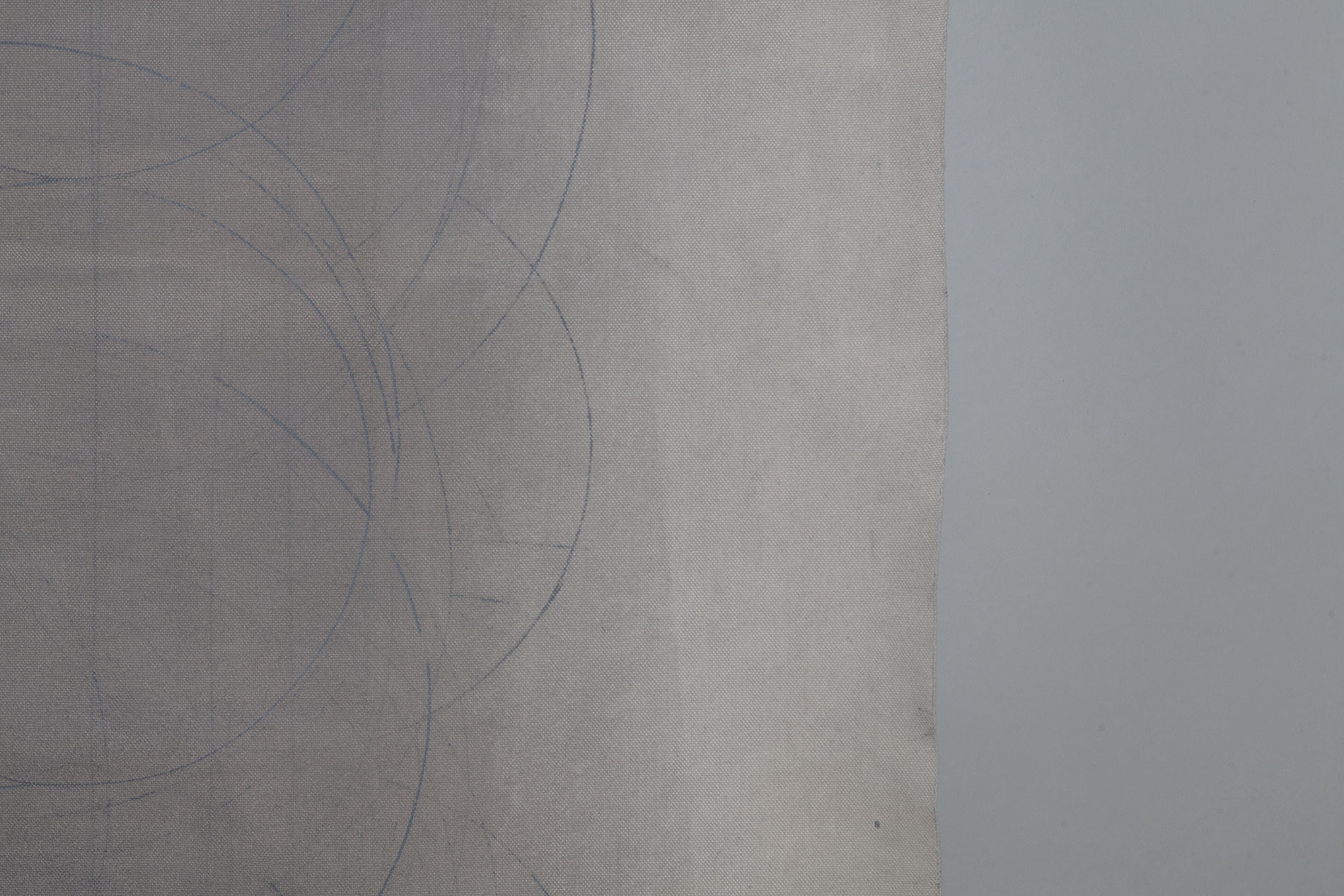

One of the students’ pivotal assignments is to keep a logbook. This reflective tool provides a record of what’s going on in their minds as they create. They can make sketches, talk about an artist whose work they admire or comment on how to adjust their glaze for the next try. There are no rules; no good notes or bad notes. The only requirements are to examine their motivations and to be present to the process of artmaking.

I adapted this course from my own process. Ceramics requires detailed notetaking to track variables such as firing temperatures, kiln placement and glaze formulas (see “True Colours” for an example). The logbook works in tandem with these notes, letting students develop an awareness for how a piece is evolving, not just technically but thematically.

To grade the students, I look for coherence. A piece that cracks or warps in the kiln is not necessarily poorly marked if it’s in line with the observations made, the effort put in and the lessons learned.

In time, students learn to see overarching themes in their logbooks, where they once saw only seemingly unconnected ideas.. With practice, they’ll learn to look at their finished pieces and instinctively read the story written there.

A piece that cracks or warps in the kiln is not necessarily poorly marked if it’s in line with the observations made, the effort put in and the lessons learned.

N° 6

Power

September 2018

by pascale girardin Photo by stephany hildebrand

Empowerment is a word that gets a lot of air time these days.

Empowerment is a word that gets a lot of air time these days. It’s associated with big movements like #MeToo, #BLM and #TimesUp, and it emerges in smaller, more subtle contexts. As I write this from the lounge of a popular Montreal music venue, I’m aware that a poster in the restroom advises patrons who “feel threatened in any way” to alert the bartender. Empowerment in the feminist movement has often come to represent, not even a desire for power, but simply for wellbeing. It’s about defining safe and healthy spaces.

This got me thinking about what the word “power” actually means. There’s the traditional definition that we associate with dominance. But power, in language, takes many forms. As a ceramicist, I’m interested in the ways that this notion manifests. To do my work, I require physical power, the strength to prepare the clay by wedging it a hundred times over (as you’ll read about in Thin Edge of the Wedge). There’s willpower, the ability to self-administer discipline, which my interview with kickboxer Carline Pierre Jacques in Defining Self reveals can be utterly transformative. Then there’s staying power, the idea that small actions over time create a profound impact. This has been as true for me in my 22 years of ceramics as it has been for the mill in Sanbao, China (described in The Shape of Water) from which a tiny trickle is all it takes to pommel some of the world’s finest porcelain clay into being.

“Drift” is my way of explaining how meandering thoughts can crystallize into a fully formed idea. It’s the origin of creative thinking and my mantra for daily life.

I invite you to drift with me.

Pascale Girardin

There’s the traditional definition of power that we associate with dominance. But power, in language, takes many forms.

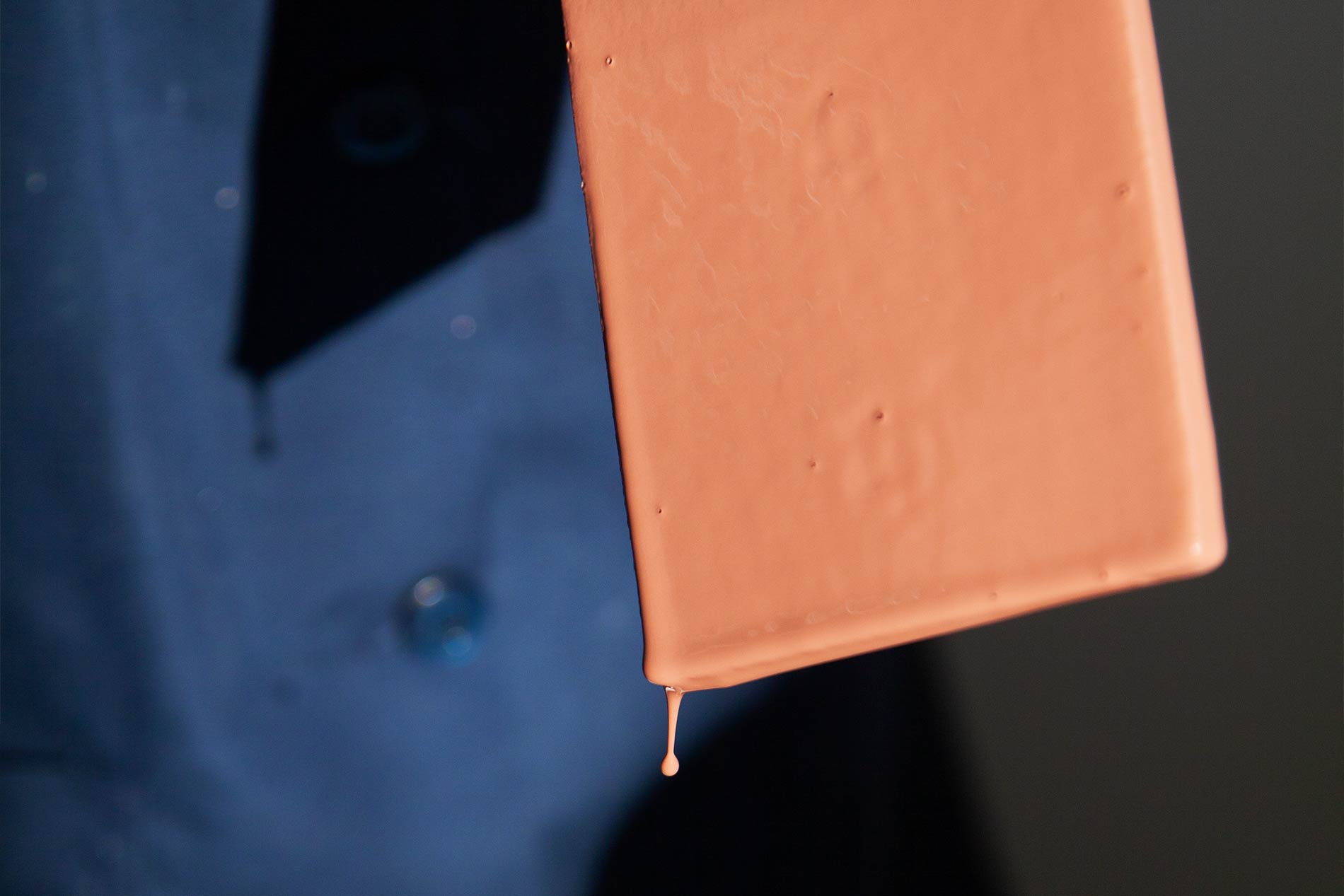

by pascale girardin photos by stephany hildebrand

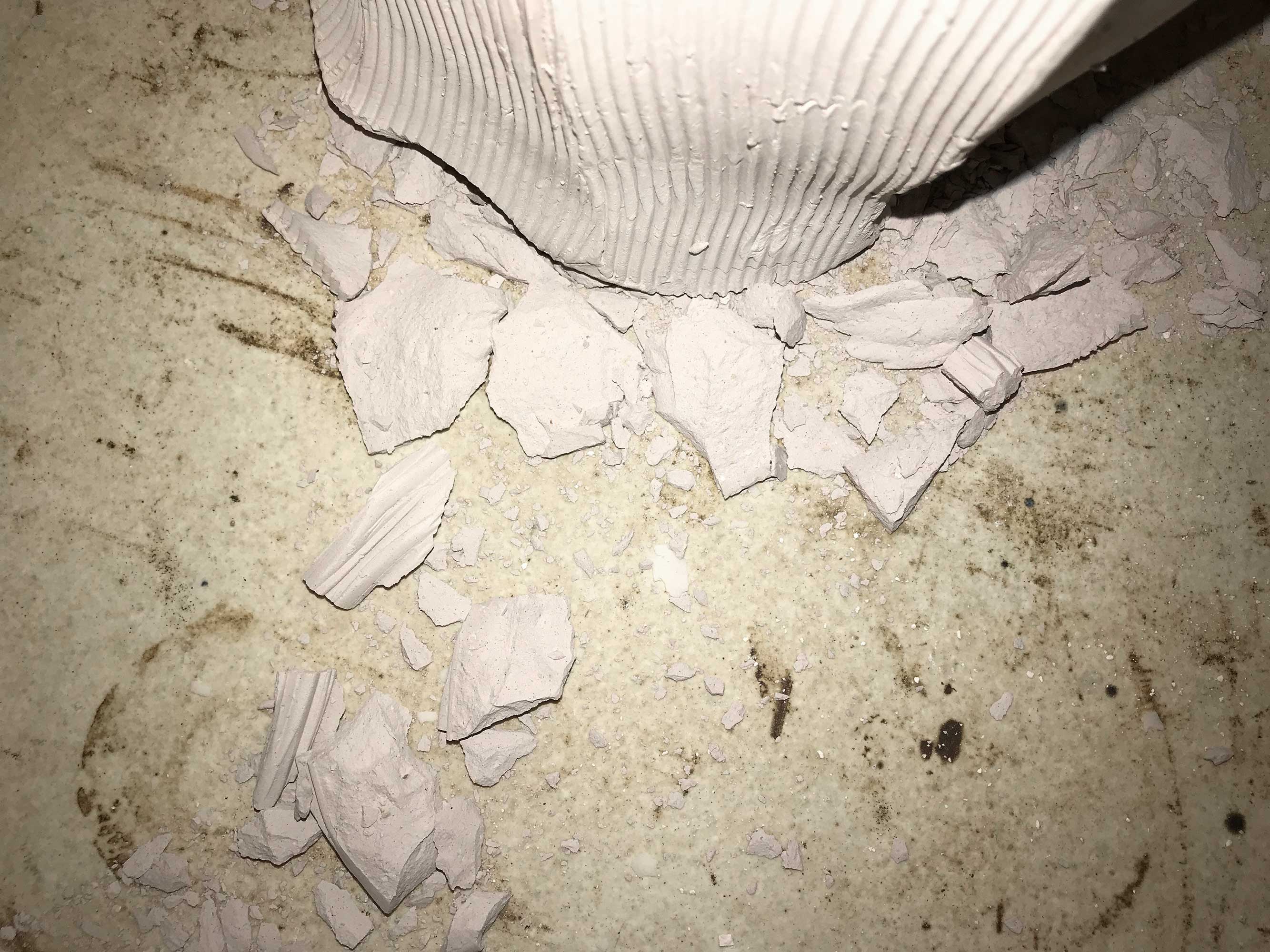

The process of preparing clay is as much an artform as the works it produces.

No piece of fresh clay can be hand sculpted, molded or wheel formed without going through the process of wedging. To prepare the clay, the ceramicist must first work it into malleability. It’s a bit like kneading bread, except, whereas the goal there is to work air into the dough, in wedging the objective is to take air out and homogenize the clay body. Trapped air pockets can have devastating effects, which can ultimately cause a nearly finished piece to explode in the kiln—obviously not what you want after you’ve lovingly coaxed a work of art into existence!

Wedging is itself an artform. The experienced ceramicist must be able to read the clay well enough to know when she has reached the precise balance between just enough, so that the clay is free of air bubbles, but not so much that it becomes dry and fatigued. Its density must be consistent and, at a microscopic level, the individual platelets of the clay must align to prevent the pieces from warping as they dry.

Wedging is an intensely physical process, requiring not just the hands, but the whole body. (I remember the soreness in my abs when I first started to learn.) There are different types of wedging styles, but I prefer the Japanese method of spiral wedging. Here, the left hand holds the clay laterally while the right pushes it forward. This technique makes use of body weight over muscle strength. In that way, wedging shares a similarity with the martial arts’ philosophy of using minimum energy to achieve maximum power. And trust me, you need that edge to keep it up for the 120 or so manipulations required to prep a single piece of clay!

I have long appreciated the ritual of wedging for the mental preparation it provides, and the connection it builds between artist and material. When the clay has been wedged, it has a distinct shape that is at once raw and beautiful. That form is something I’m celebrating in a new series. Called “Prologue,” the pieces are composed of clay that I cut after wedging, then reassembled. The finished works give insight into the individual character present in each and every block of clay.

Wedging is itself an artform. The experienced ceramicist must be able to read the clay.

by pascale girardin photo by stephany hildebrand

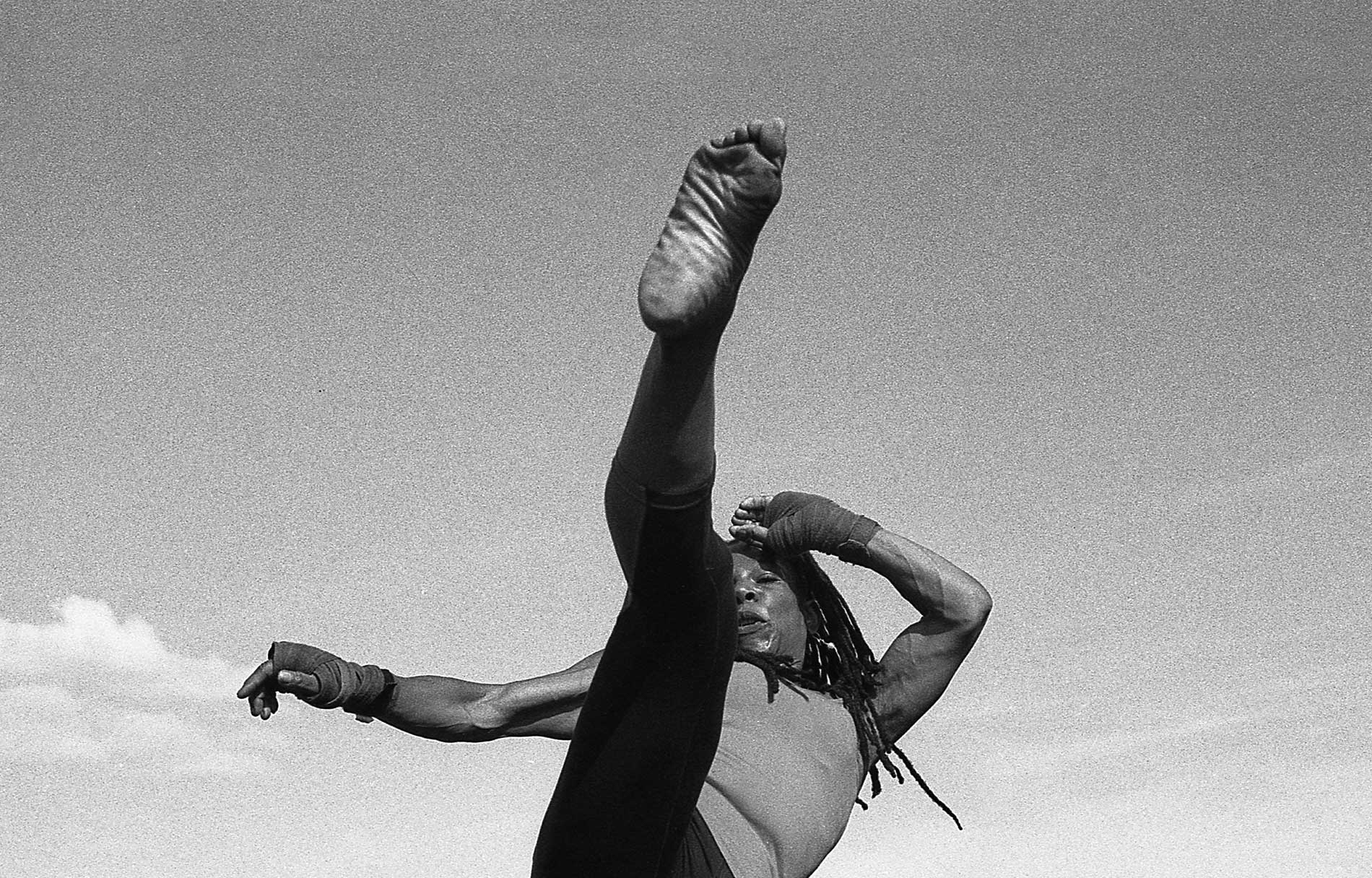

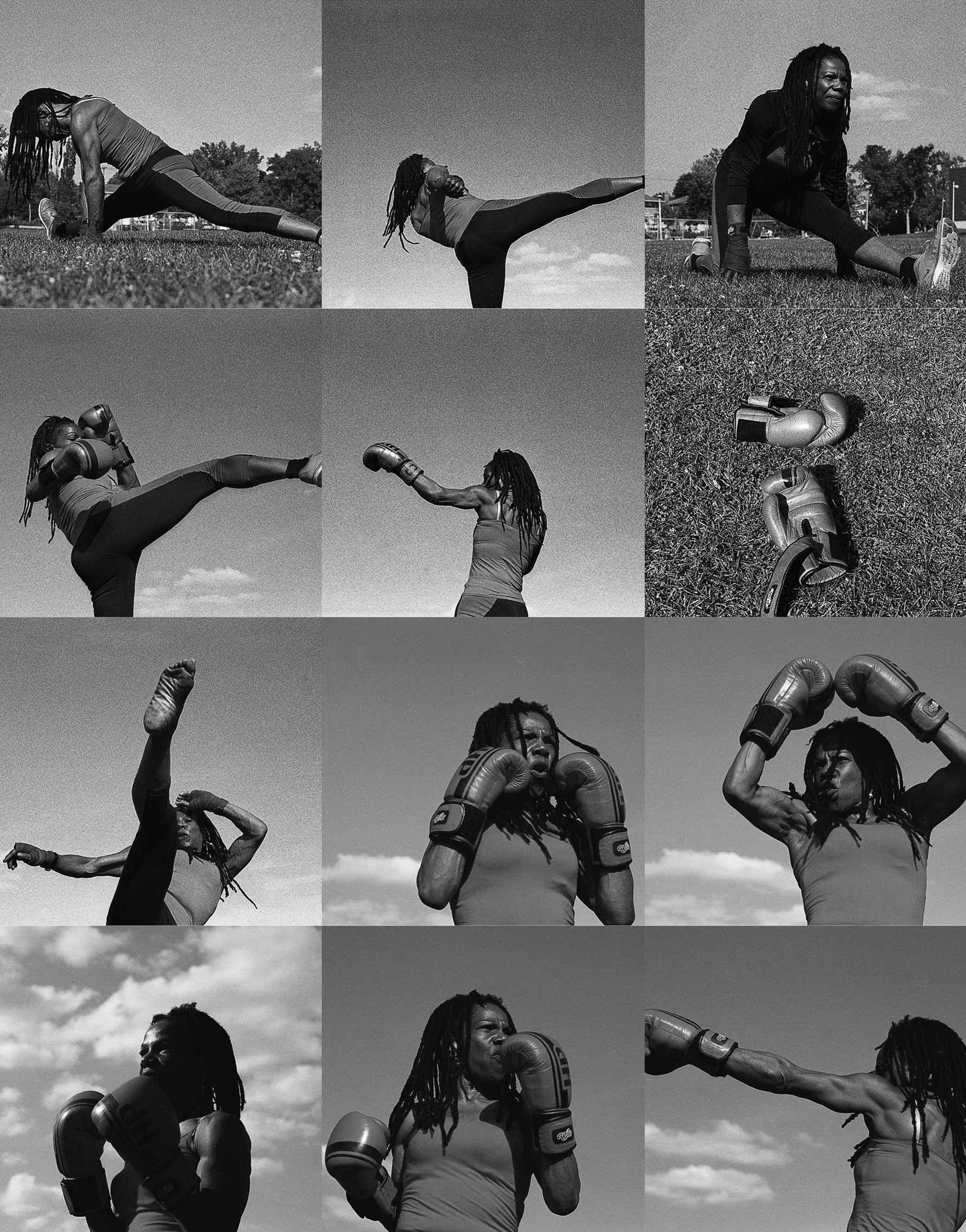

Through kickboxing, Carline Pierre Jacques goes beyond physicality to help women develop their inner strength.

Before Carline Pierre Jacques took her first kickboxing class, she says “I was gaining weight, my life was out of control, my marriage was on the rocks and I had a boss from hell.” But the highly demanding sport turned her life around in many unexpected ways. Jacques was the only woman in her class, but she felt women especially could benefit from kickboxing. In 2011, she founded the Montreal studio Amazon Fitness, focused on teaching empowerment and self defense. Today, Pierre Jacques’ method of training goes beyond the physical, so that the power that her clients develop can impact every aspect of their lives. Here, she describes her experience in her own words.

The most amazing thing about a fighter is not winning or losing, but facing your opponent. In kickboxing, we learn to practice, to throw a punch a million times and start over again until it becomes effortless. We learn to conquer fear and take hits. We learn to roll with the punches or back down because knowing when not to fight is just as important.

Kickboxing changed my life and it changed my world view. When I joined my first class, I had suffered a series of unfortunate events and was depressed. I was gaining weight and no amount of dieting or exercise was helping. But I was immediately swept up in the demands of the sport. Soon weight loss ceased to be an issue. My goal became instead to make my body strong, since I was the only girl in the class and had to keep up. Through my practice, I was aware that I was becoming more resilient. I was learning to get up when life knocked me down.

The most amazing thing about a fighter is not winning or losing, but facing your opponent.

We live in a world that takes the body for granted. We know it’s important to nurture the soul, but if you nurture the body, you’re considered vain. We separate spirituality from our physical selves. But, for athletes, strengthening and cultivating our bodies is spiritual. It’s being in the zone, in the moment.

I was transformed by kickboxing. It made me open my own business. Amazon Fitness is a forum where I encourage women to love themselves, to build strong muscles and to create beautiful bodies. I teach kickboxing, body toning, aero boxing and self-defence, since it’s important that all women learn to defend themselves. But it’s really about creating the warrior women of today.

Écrasement I – 2013 Porcelaine, glaçure, pigments / Porcelain, glaze, pigments 14.3 x 38.5 x 22 cm. Private collection Photo: David Bishop Noriega

Artist Laurent Craste uses acts of violence to create delicate ceramic sculptures that pack a powerful message.

Montreal-based Laurent Craste has defined his ceramic work by destroying what he creates. Craste puts his reproductions of historic vases, busts and other objets d’art through extreme abuses. Those might include trampling, stabbing, defacing with graffiti, beating with a baseball bat or even ramming with a brick. Even so, the pieces remain recognizable as decorative objects. By willfully corrupting these icons, he disrupts our notions about the historical, social and aesthetic value they represent, and creates a new aesthetic in the process. Here is independent curator Pascale Beaudet on Laurent Craste.

Portrait of Laurent Craste with Iconocraste - O Photo: David Bishop Noriega

Laurent Craste explores the notion of power by focusing on the dominant French classes of the 18th and 19th centuries, who commissioned very beautiful objects d’art, including vases from the famous French porcelain manufacturer in Sèvres. The artist is particularly interested in how the elite of that time used economic power and aesthetics as instruments of propaganda.

And while his works examine the power the elite exuded over the masses, they are also a commentary on the latter’s retaliation. The violent acts that Craste subjects his reproductions to draw reference from peoples’ uprisings of the French Revolution of 1789 and the Paris Commune of 1871, during which works of art and buildings, once held by the upper classes, were routinely destroyed.

In his vases, we see the objects’ delicacy contrasted with the solidity of the tool used to disfigure them. We also see a juxtaposition of eras and methods of fabrication: the hand-crafted objects of the 18th and 19th centuries, with the tools machined in 20th-century factories.

Révolution III – 2016 Porcelaine, glaçure, hache Porcelain, glaze, axe 77 x 30 x 43 cm. Photo: Daniel Roussel

To determine the mode of destruction for each piece, Craste develops his works in reverse. Both the clay and the tool must be tested in the kiln. It means conducting numerous experiments—and also suffering many losses. Ultimately, the material composition of the tool determines at which stage of the process it will be integrated into the piece. As to the choice of tool, it’s the shape of the decorative object that determines it.

Craste says that, given the number of losses, which can account for nearly half of his overall production, his greatest satisfaction is in realizing that one successful piece. Conversely, he feels an intense frustration when the object collapses. It’s at that point that the porcelain exercises its power over the artist.

by pascale girardin photos by pascale girardin

From a porcelain mill in China, we learn about the remarkable power of small actions.

For nearly two thousand years, the town of Sanbao in China’s Jingdezhen prefecture, has produced the ultra-white porcelain used by the country’s royal households. But while dynasties rose and fell, the work produced in Sanbao endured. Today, the location is considered the world capital of pottery and is home to a prestigious international ceramics institute.

Earlier this year, while completing an installation in Shanghai, I had the opportunity to visit Sanbao and watch its traditional method of clay production. I witnessed the clay—the rare streak of porcelain known as kaolin—being collected into water basins. I saw the floor covered with the silky, white substance, and watched as it was shaped into squares and dried for distribution. But the most impressive part of the facility, now a Chinese heritage site, was its hammer mill. Set in motion by a mere trickle from a nearby creek, this water wheel powers several impressively-sized mallets that pummel the raw mud into its purest form.

It reminded me that we can all strive to be a little like that tiny trickle. Water has its ways. It can freeze inside a rock and split it in half. It can drip for a thousand years and make a pool in stone. When you pour it in front of an obstacle, it will find the simplest way around it. What a wonderful analogy for power!

by pascale girardin photos by stephany hildebrand

What working in a fussy medium has taught me about staying power.

I chose to make a career out of mud. To look into that mud and say I see beauty, I see luxury, I see pieces that will grace the world’s finest hotels, restaurants, shops and private residences. My relationship to that mud has been the longest of my life. That requires staying power.

How many things can go wrong on a ceramics piece? Let me count the ways. Pieces can explode in the kiln. They can be maimed by the shrapnel of other explosions. They can sag or warp. They can get pitholes, or bubble, or split. Glazes can come out wrong. They can be glossy when you want matte, opaque when you want translucent, and vice versa. The colours can drip and cake. They can expand at a different rate to the clay and cause the ceramic to fracture.

Of course, none of this shows up right away. To see the extent of the damage, you have to have patience. You have to wait. The kiln fires over a 12-hour cycle, at 1,200 degrees Celcius. And, before you can even open the door, you must give it another 12 hours to cool. Only then, 24 hours later, does every error committed to the piece, every imperfection of material, show up. A flaw may have been introduced months earlier in the wedging, the drying, the first firing, the second. To know what went wrong, you need to have a good memory. You have to take lots of notes.

Some of the flawed pieces get put aside. I’ll think that maybe, given time, I’ll like them. Some, I discard because I’ve learned something new. Occasionally I’ll have a premonition that something has gone wrong, and, even before the kiln door opens, I’ve moved on. You can’t cry over spilled milk in this craft. If you do, you’re not in the right field. You will fail the clay and the clay will fail you. All you can do is look into the next batch of mud and dream.

N° 5

History

April 2018

by Pascale Girardin illustration by pascale girardin

In contemplating a theme for this issue, I looked to Black History Month. My idea was to reach out to artists of colour from across North America and ask them to share stories from history that have special significance to them.

I planned to publish the interviews I collected in Drift all year long. After all, why be limited to a month?

But in the background, I questioned my own motivations. I kept wondering, “Why am I interested in this? I’m white.” This thought put me into a weird space, a kind of feedback loop in which I ossilated between “we all belong in the conversation” and “this not my place.”

After seeking the council of a trusted friend well versed in black history, I veered my inquiry to the broader topic of history as a social construct with a dominant narrative. To free ourselves from it, we must acknowledge that there are numerous versions of history. It’s only by being receptive to this multifaceted definition that we can better understand one another. We have to – because every day, we’re making history as well.

So in this issue, we explore history first through the perspective of ancestry, then through the lens of jazz, one of my favourite musical genres, and a theme that came up again and again in the conversations I had with the people who contributed to this issue.

In Harlem of the North, DJ Andy Williams tells of the nearly forgotten inter-war jazz golden age in Montreal; This is not a Tree looks at the multitude of lives that went into the creation of our own; and Blue Note explores the work of Jennie C. Jones, an artist who uses the unlikely aesthetic of minimalism to actually call into question black music’s exclusion from modernist visual art.

“Drift” is my way of explaining how meandering thoughts can crystallize into a fully formed idea. It’s the origin of creative thinking and my mantra for daily life.

I invite you to drift with me.

Pascale Girardin

by pascale Girardin photo by Saad Al-Hakkak

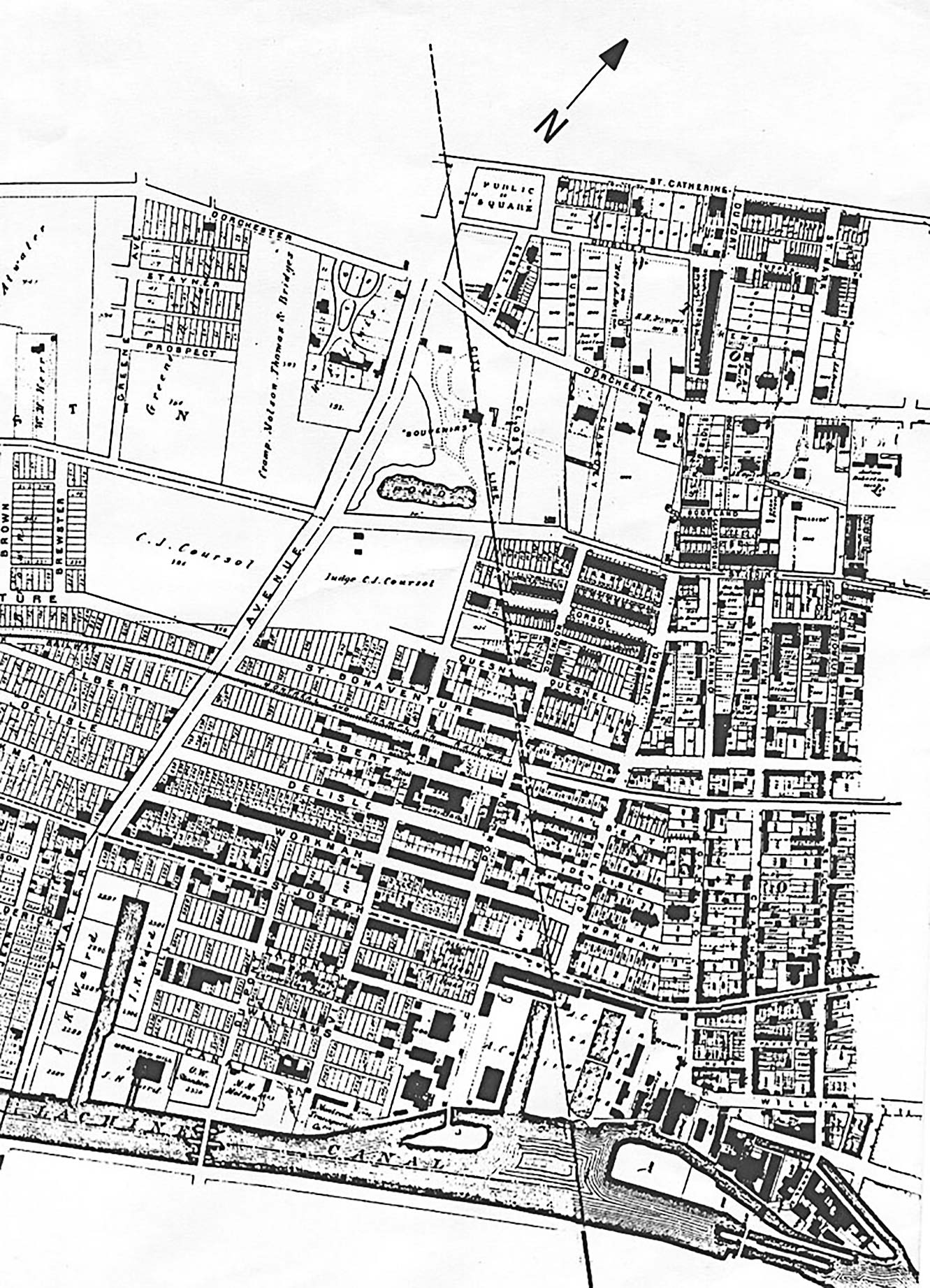

DJ Andy Williams on Montreal’s remarkable inter-war jazz age.

DJ, radio host and promoter, Andy Williams is a heavyweight on Montreal’s music scene. From 2002 to 2017, as one half of The Goods Sound System, he and partner Scott Clyke brought some of the world’s top DJs to their monthly dance parties at the Sala Rossa. Williams grew up in the U.K. but also spent part of his early life in New York and Toronto, as well as his mother’s native Jamaica. His tastes reflect the diversity of his background with influences that range from gospel to electro.

I asked Williams to contribute a story to Drift’s History Issue. He shared this article on how Montreal, through an influx of black immigrants from Nova Scotia, the United States and the Caribbean – along with the music they brought with them – became known, between the World Wars, as “Harlem of the North.”

“While working as an Educational Coordinator in the heart of the predominantly black ‘Little Burgundy’ community where this all took place, I met many veterans who got me inquisitive about the area’s history,” says Williams. His article presents a fascinating look at the meteoric rise of jazz in Little Burgundy; the surprising people who nurtured such international talents as pianist Oscar Peterson, tap dancer Ethel Bruneau and guitarist Nelson Symmonds; and the circumstances that would ultimately lead to the demise of Montreal’s jazz golden age.

Read Andy's article here.

Musicians would play regular jobs from 9 PM to one or two in the morning, and then search out the jazz clubs that used to stay open.

By pascale girardin photos by michel dubreuil

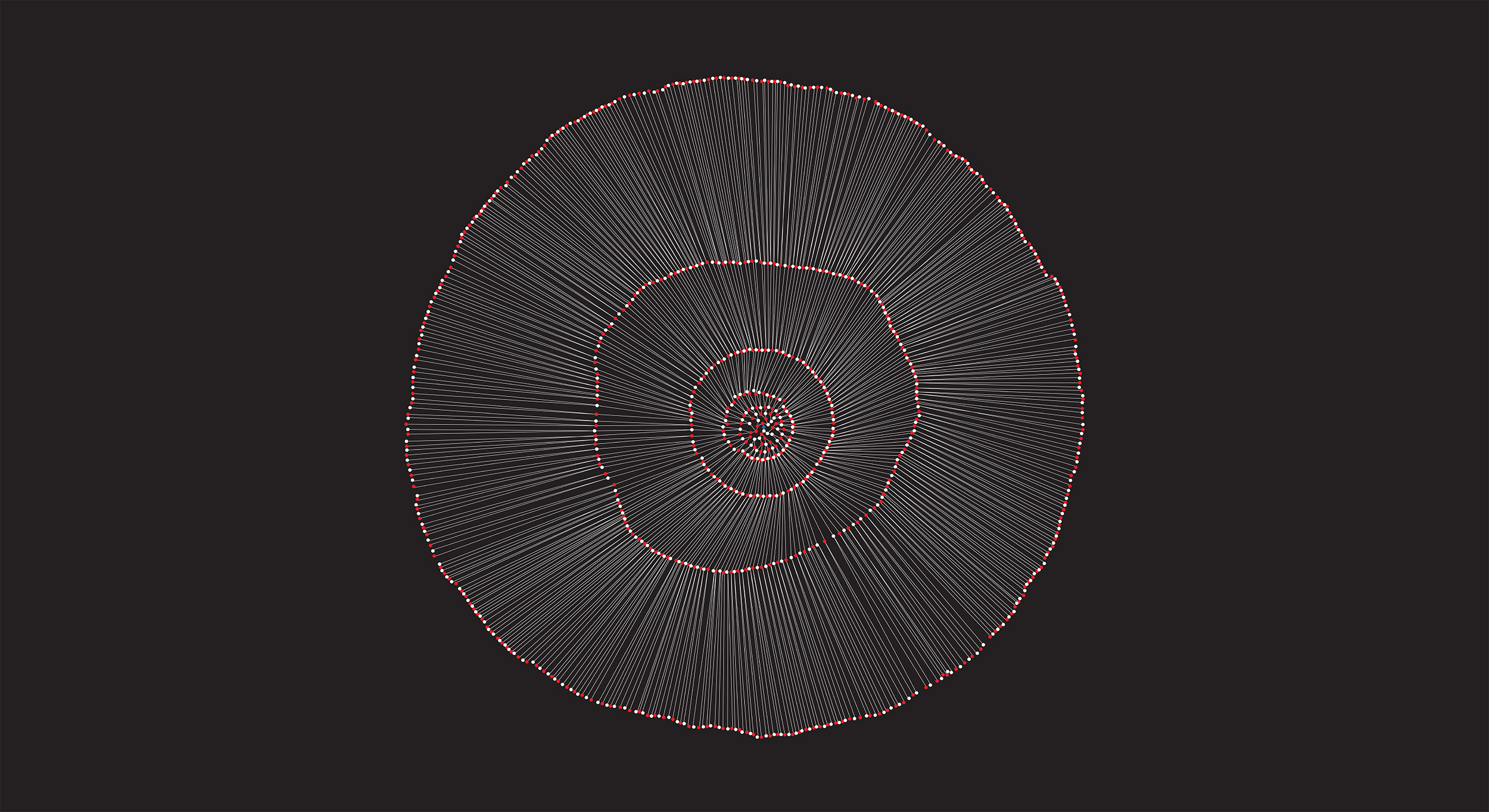

A sculpture tracing 10 generations reveals the complexity of ancestry.

In 2011, I was invited, along with nine other artists from the Americas, to create an outdoor sculpture for the International Symposium of In-Situ Art. The theme was “legacy.” We were each allocated a site along the four kilometres of trails at Les Jardins du Précambrien in Val-David, Quebec. Mine was to be a very large glacial boulder.

My concept was to shroud the rock in a lineage pattern known as cognatic descent. Unlike the more common agnatic structure – otherwise known as the standard family tree that traces paternal branches – cognatic follows the origins of mothers as well as fathers. (Think of it as a web with you at the centre and your ancestors spreading out radially in all directions.)

Just imagine all the hopes and loves, successes and hardships of those two thousand lives. Imagine the stories our webs could tell!

Over two weeks, my team and I constructed the work, entitled “This is not a Tree,” using gray glazed ceramic disks for women and white for men, linked together by metal wires. They flowed from a central disk position at the top of the rock and the heart of the sculpture. In all, it took 2048 disks to represent the number of people who, in 10 generations, went into the making of one individual.

By displaying each ancestor as a circle of clay, we get a snapshot of the scale of our origins. But just imagine all the hopes and loves, successes and hardships of those two thousand lives. Imagine the stories our webs could tell!

Of all the comments I received on the sculpture, one stuck with me as the most poignant. It was from a friend who had been adopted as an infant. She told me that she always felt that a part of her was missing because she had never known her birth parents. But in seeing the true number of lives that had formed her own, she said she had found some peace.

by pascale girardin

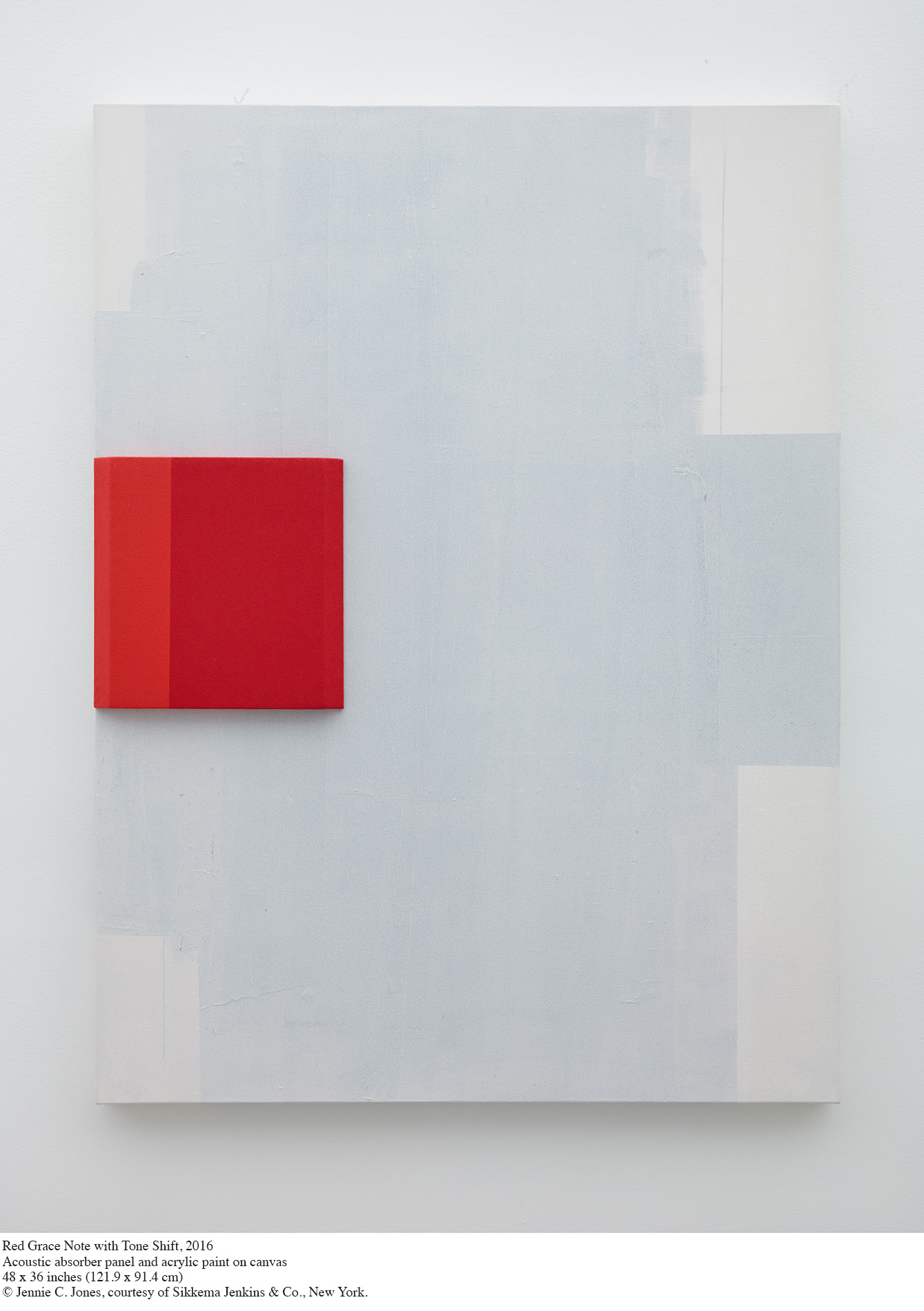

Jennie C. Jones: Compilation Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, 2015-16 Photo: Paul Hester Artwork © Jennie C. Jones, courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

Jennie C. Jones explores the language of experimental jazz through minimalism.

For me, one of the most exciting artists working to redress history today, is Jennie C. Jones. The artist from New York takes conceptual art – a genre overwhelmingly occupied by white male artists – and adopts its language to address the historical appropriation of jazz into academia and its absence within the canon of contemporary visual art. The result is that each piece reads like a puzzle: minimalist and austere in form; complex and politically charged in significance.

Her audio-visual explorations incorporate abstract paintings on acoustic panels, noise-cancelling instrument cables arranged as sculpture and sound clips spliced into sonic collage. The most moving is perhaps her piece entitled What a Little Moonlight (2007), in which a single note from Billie Holiday’s final performance in 1957 at the Newport Jazz Festival (predating Jones’ piece by exactly 50 years) is looped to produce a haunting, hypnotic lament.

There is a poetic nature to minimalism that is about striking a balance between full and empty… A single extended note could have a weight and simultaneous lightness. Something being busy or crowded does not make it more fulfilling to me.

As Jones told the Huffington Post, “There is a poetic nature to minimalism that is about striking a balance between full and empty… A single extended note could have a weight and simultaneous lightness. Something being busy or crowded does not make it more fulfilling to me.”

Jones explained her desire to use modernism as a means to comment on the African-American musical experience like this: “I would not say [they are] at odds, I hope that my work can point out the parallel relationships between the ‘social practices’ of black music at mid-century (and beyond) as well as its overt connection to dominant visual ‘isms’ historically. What’s more that it presents a place for that discourse to expand.”

The works of Jennie C. Jones are much more than meets the eye (and ear). With so little signal coming from them, they demand that you pay attention.

by pascale girardin photos by stephany hildebrand

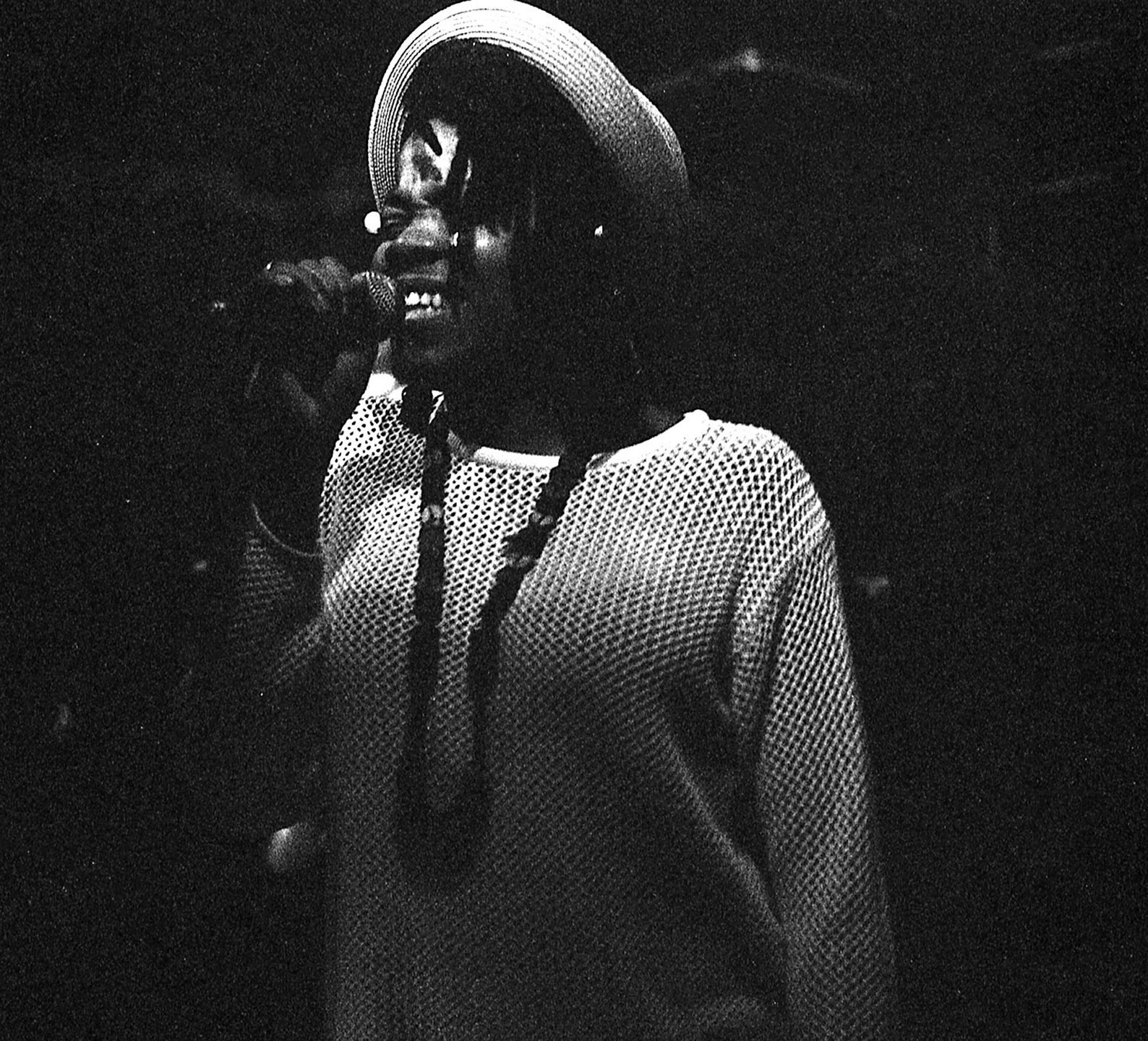

Malika Tirolien on Montreal as a modern jazz city.

Montreal’s current jazz scene is perhaps most associated with the Montreal International Jazz Festival (June 28 to July 7), now in its 38th year. And while today’s event, which represents over 3,000 artists from more than 30 countries, covers a diverse array of musical genres, one regular performer who stays true to its original mandate as a jazz showcase is local talent Malika Tirolien. The Guadeloupe-born singer-songwriter is prolific in her work as a soloist, as well as with the improve group Kalmunity Vibe Collective and bands like New York-based Snarky Puppy and its offshoot Bokanté, which means “exchange” in Creole. Her music is heavily steeped in French-Caribbean music and traditional jazz. Here she describes Montreal’s modern jazz scene and where it’s headed.

In Montreal, people can create while being relaxed compared to other cities like Paris and New York where the hustle is nonstop

Pascale Girardin: I’ve been learning about Montreal’s jazz history in Little Burgundy, through my interview with Andy Williams of The Goods Sound System and was wondering if you are familiar with that period and if you see aspects of its legacy in the current jazz scene?

Malika Tirolien: I actually heard about it recently thanks to one of my best friends. Apparently, Little Burgundy saw the rise and golden days of Montreal’s jazz scene between the ’20s and ’50s. I heard there was a particular club called Rockhead’s Paradise, owned and founded by Rufus Rockhead that was the place to be at the time.

I think the legacy of this era is quite big since it shaped the future of jazz music in Montreal until today. Because of Little Burgundy, people like Rouè-Doudou Boicel, owner of the Rising Sun Jazz Club, who created the original Montreal Jazz Festival (called The Festijazz) in the late 1970s, and music promoter Charles Biddle who also created jazz festivals in the city in the early ’80s, got inspired and re-implanted the genre in Montreal. The Montreal Jazz Festival and the jazz clubs that we know now wouldn’t exist without these pioneers.

PG: What do you like about Montreal as a base for your music?

MT: I like the diversity of the music in Montreal. It reflects the diversity of the people that live here. There are so many cultures creating music that it’s becoming more and more difficult to put them all in one box. I am a part of the Kalmunity Vibe Collective, the biggest collective of artists in Canada. It is celebrating 15 years of improvising in Montreal through its two weekly events at Petit Campus and Resonance Café (my favorite jazz place with vegan treats).

PG: How would you compare Montreal’s modern jazz scene to other centres?

MT: It is really rich but also really mellow. In Montreal, people can create while being relaxed compared to other cities like Paris and New York where the hustle is nonstop. The only thing that I find very disappointing in Montreal is the fact that its huge musical community, full of talents of all horizons, are not all represented in the mainstream media. It is time for Montreal and the province of Quebec in general to acknowledge its diversity in all domains and give space and recognition to all types of Quebecois artists.

PG: What is your hope for the future of jazz in Montreal?

MT: To see it represented by people of different cultures. I want to hear more Caribbean jazz, Latin jazz, Ethiopian jazz, hip hop jazz, et cetera. I’d also like more clubs to open and maybe see another golden era of Montreal jazz!

Malika kalmunity Café resonance Snarky puppy

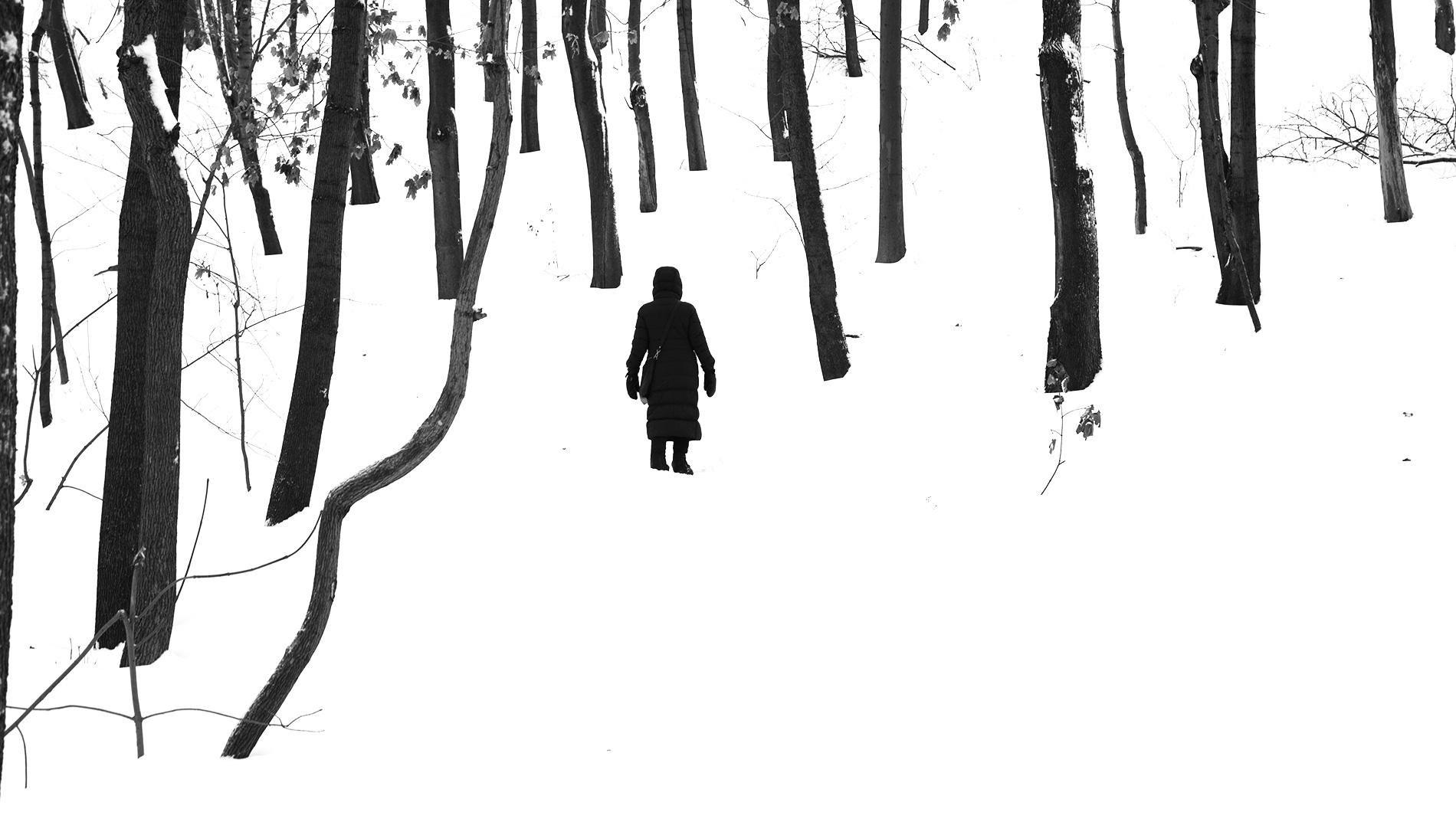

By Pascale girardin photography by Stephany Hildebrand

In Montreal, we get through winter by embracing it.

The city spends six months under a thick blanket of snow. To the uninitiated, it seems like a lifeless season. But explore it and you make discoveries, like how the dried golden field grasses that peek through the white landscape are still alive under the earth, waiting to turn green again in the spring. Or how, when you peer through a transparent patch of pond ice, you spot the bubbles of fish swimming just below the frozen surface.

This issue, we examine the notion of dormancy. We live in a time when activity has turned into a permanent state of being. We are expected to produce at lightning speed. I want, instead, to celebrate the uneventful. Dormancy means trusting that things are operating without any activation on our part.

“On Drying” looks at how, just as the ceramist must step back during the drying process, so should the mind be permitted times of dormancy to achieve its potential. “Scream at the Wall,” delves into an instruction manual by Yoko Ono for achieving… nothing. And “Unexpected Communion” reveals how the invisible elements of terroir shape a wine’s flavour in surprising ways.

“Drift” is my way of explaining how meandering thoughts can crystallize into a fully formed idea. It’s the origin of creative thinking and my mantra for daily life.

I invite you to drift with me.

Pascale Girardin

Dormancy means trusting that things are operating without any activation on our part.

By pascale Girardin Photography by Stephany Hildebrand

The transformative act of letting things be.

Patience is the first lesson of ceramics. Clay needs time to dry. It can take an hour for a bone china flower petal, or a few months for a thick-walled bench.

As clay dries, it shrinks by about 10 percent. A piece that begins at 100 centimetres, can compress by 10. We help that movement along by placing the object on smooth cotton so it can gently slide, obeying a natural law that we know happens, but is too subtle to see.

This property of clay gives us an analogy for other life cycles. As a painter, it took me 10 years to realize that I have a two-year pattern of production: six months of work and 18 months of having nothing to express. Had I not observed and allowed myself the time to make that connection, I could easily have given up, comparing myself to more productive artists.

Instead, something told me to be patient. During the quiet times I travelled, visited friends, took classes. It seemed the ideas would not come until they were ready for the canvas. When they did, each new painting series became a departure from the one before.

It’s taught me that we must not resist our downtimes. Like drying clay, they allow us to shift imperceptibly into a new stasis.

by pascale girardin Photos by stephany hildebrand

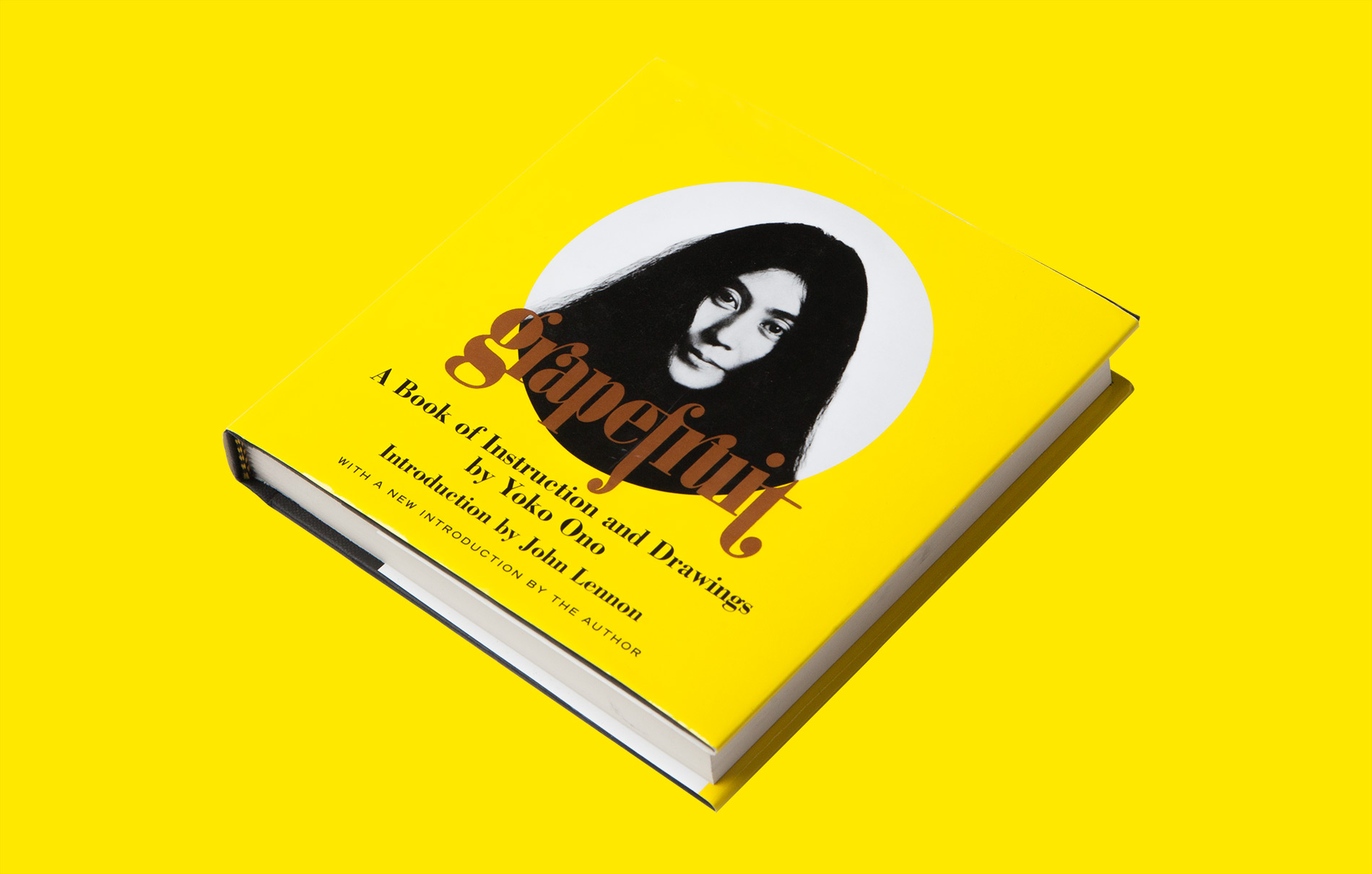

Inside Yoko Ono’s instruction manual for doing nothing.

This issue’s theme of dormancy can be expressed as “Process” being both the means to an end and the end in itself. One of the most wonderful and illuminating books I’ve read on this idea is Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit: A Book of Instructions and Drawings. In it, Ono outlines dozens of directives for creating works of art.

Some can be easily executed…

Shadow Piece Put your shadows together until they become one. 1963

While others, less so…

Tape Piece I Take the sound of the stone aging. 1963 autumn/

And some combine a bit of both…

Stone Piece Find a stone that is your size or weight. Crack it until it becomes a fine powder. Dispose of it in the river. (a) Send small amounts to your friends. (b) Do not tell anybody what you did. Do not explain about the powder to the friends to whom you send. 1963 winter

I love this book because there is no result to these instructions, their actions lead nowhere and they don’t produce anything. Instead, they’re about giving life to experiences that are ours alone to delight in.

When people ask me what the most important thing is in life, I answer: ‘Just breathe.’

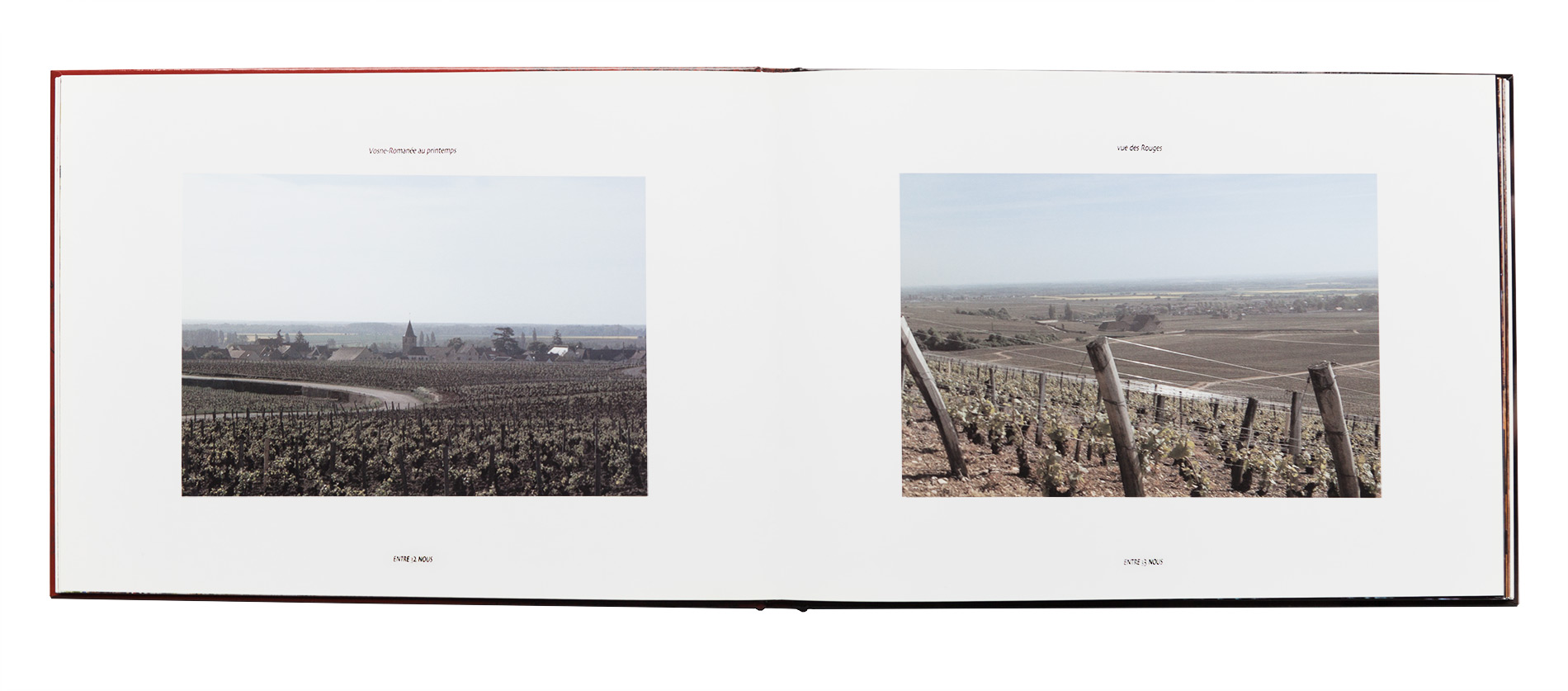

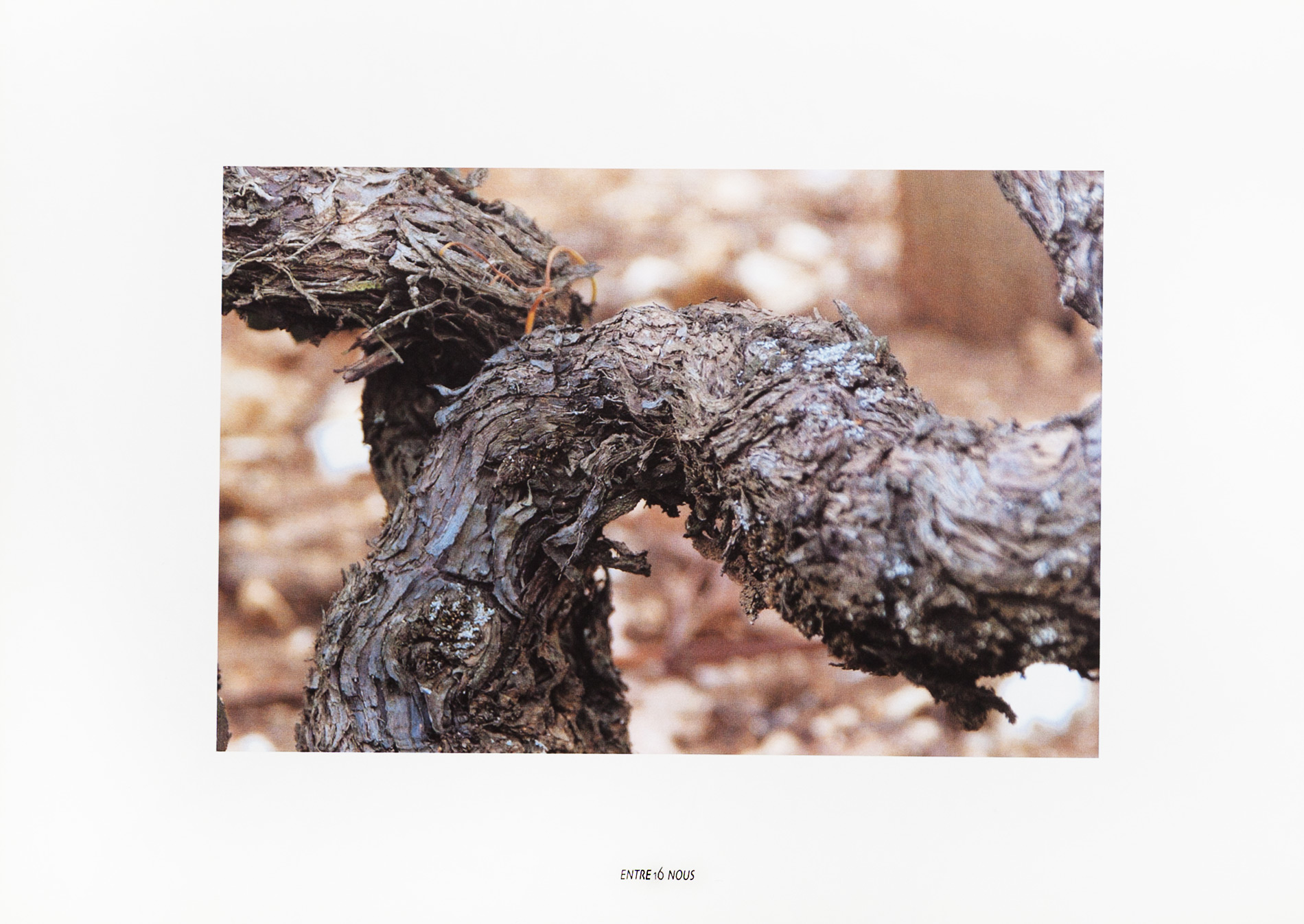

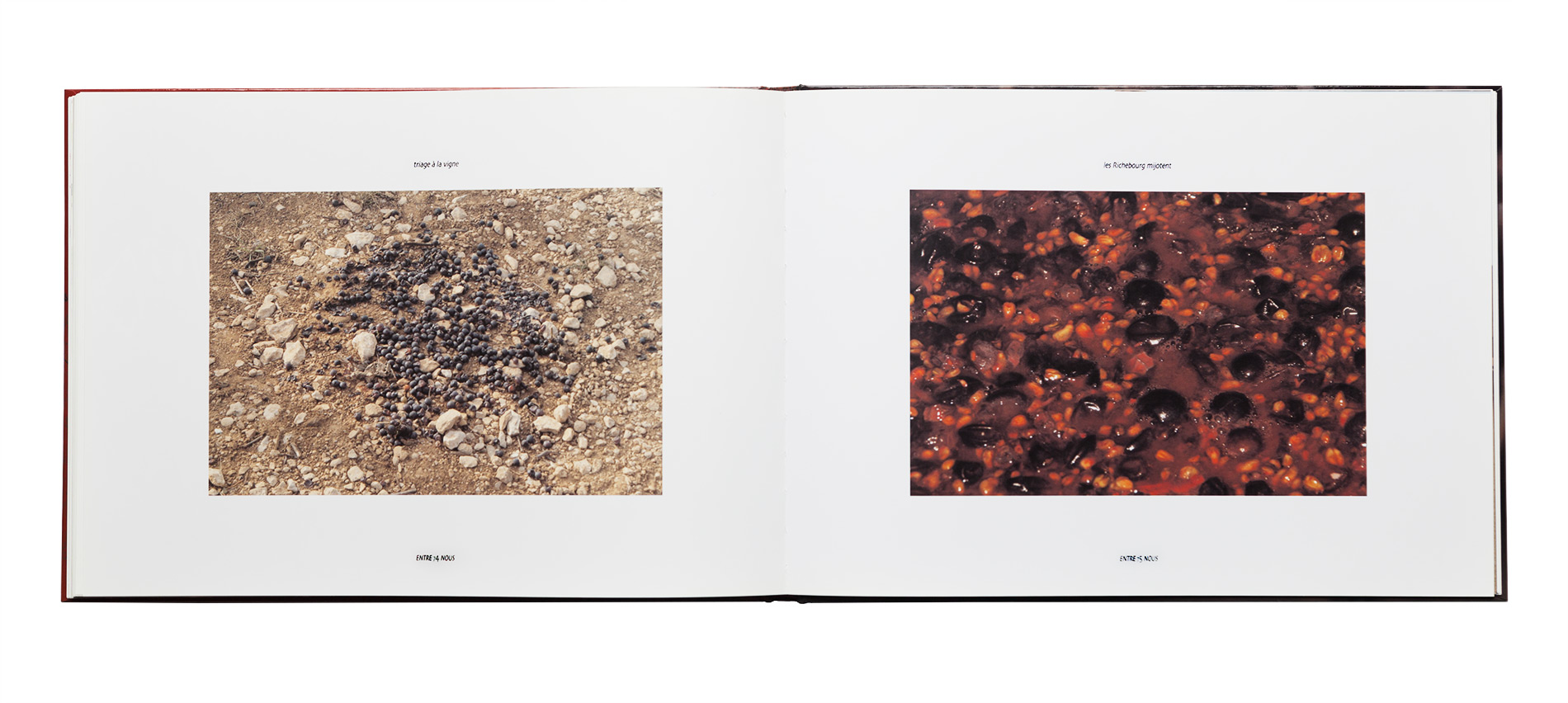

by Pascale Girardin Book courtesy of Domain Grivot

An evening in Burgundy reveals the definition of wine terroir.

Seven years ago, I met the French winemakers Étienne and Marielle Grivot at a cottage party in Lac Estérel, Quebec. When they learned that I would be in Paris later that year, overseeing a ceramic installation for the department store Printemps, they insisted I overnight at their Burgundy estate.

I arrived with some trepanation, knowing that, although I have an appreciation for fine wine, I was far being from a connoisseur. The couple greeted me warmly and we sat down at the family kitchen table.

Just before we began the hearty main course of duck confit, Étienne opened a new bottle and poured me a glass. From the first sip, I felt instantly transported.

What were my thoughts, they asked, and I shyly responded that I lacked the wine vocabulary to describe them. “Everyone has their own words,” said Étienne. “You felt something. Tell me what it was.”

I explained that I heard voices rising in ecclesiastical song, the notes flowing like silk through the serenity of a cathedral. I could smell its wood and the heady perfume of incense. When I’d finished my description, they were silent for a moment and finally Marielle exclaimed, “She’s good!”

They explained that the stones used to build the region’s gothic churches were pulled from the grape-growing soil. The wood of the pews is the same oak used to build wine barrels. This is the very definition of terroir – that the elements of the region influence the flavour of the grapes.

“Those things you described,” he assured me, “are all in this wine.”

by pascale girardin photography by stephany hildebrand

What happens when you launch an artistic challenge to do nothing.

My own version of Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit (see “Scream at the Wall”) came 10 years ago, when I made up a batch of stickers displaying empty parenthesis. The aim was to celebrate nothing.

At the time, all my energy was going into being busy: taking courses, working on projects and attracting attention to my business. The Internet was a new tool, but it was already clear that fame and fortune could be ours through online self-promotion and publicity. Today we’re used to branding ourselves on social media. But, even then, I had the sense that without the occasional detox, the production and consumption of digital content could be unhealthy. I needed a time out.

Zen Buddhism invites us to walk the tightrope between action and inaction, meaning and non-meaning. Because we don’t have words for it, we use the term “nothing.” But nothing really means “no thing.” Meditation is all about drawing balance from that space – it’s the idea I wanted to capture.

So in the then-burgeoning blogosphere, I sent out a call to my artist acquaintances asking them to join me in a celebration of nothing. I didn’t receive much response (unless you want to get Meta and say that my challenge was universally accepted). In truth, only one person took me up on it. A dancer friend climbed to the top of Montreal’s Mount Royal and performed there… for no one.

Today we’re used to branding ourselves on social media. But, even back then, I had the sense that without the occasional detox, the production and consumption of digital content could be unhealthy.

N° 3

Academia

September/October 2017

by pascale girardin artwork by Pascale girardin

In this issue, we explore Academia.

Not only do I have a love of scholarly nonfiction (more on that later), but for the last two years, I have attended the Université du Québec à Montréal, studying towards a Masters in Fine Arts.

But student or not, the autumnal notion of “back to school” is a state of mind. It’s that bittersweet time when we cast off our loose and lazy summer schedules for the sanctity of structure and routine. If you’re like me, you look forward to that mental shift.

It’s a time to clean house. As you’ll read in “Studio Code,” sponging down my ceramics studio is a meditative exercise that refreshes the mind as well as the work environment. It’s a time to challenge yourself in new ways, such as starting a personal project that falls outside of your comfort zone – I’ll tell you my story in “Out There.” It’s also a time for books, and in “What the Eye Doesn’t See” I’ll share some essential reading on the creative process from philosophical and anthropological perspectives. Tapping into creativity has life-altering benefits, no matter what your discipline.

“Drift” is my way of explaining how meandering thoughts can crystallize into a fully formed idea. It’s the origin of creative thinking and my mantra for daily life.

I invite you to drift with me.

Pascale Girardin

by pascale Girardin artwork by pascale girardin

New inspiration lies waiting in the familiar.

Two years ago, my ceramic art practice came to a standstill. The previously abundant pipeline of contracts had slowed to a trickle, my faithful studio manager was about to go on maternity leave and I found myself with more downtime than I’d had in years. Though I’ve since learned to expect the occasional slowdown, that first lull seemed interminable.

The upside of a low ebb is that it forces a reassessment of goals. For years, I had toyed with the idea of taking a Masters in Fine Arts. To develop fresh ideas, I felt I needed to be physically and mentally separated from the space where I did my commercial work. So, in my prime, I went back to school.

A few weeks in, I began to question everything. What was I going to create with this newfound freedom? What new media would I branch into? What could I possibly exhibit at the first show that was me, but not the old me? One of my professors picked up on my apprehension, and, in the visual-art-world equivalent of the adage Write what you know, he explained, “You’re sitting on a goldmine of experience: Use it.”

That’s when I did what I always do when I need to prepare my body and plot a course of action: I began to wedge clay between my hands. This rhythmic movement, the familiar prelude to making pottery, calms my busy mind in a way that staring at a blank screen or a blank canvas never can. (To readers without clay, know that any small manual task produces this cathartic effect, from kneading dough to washing dishes.)

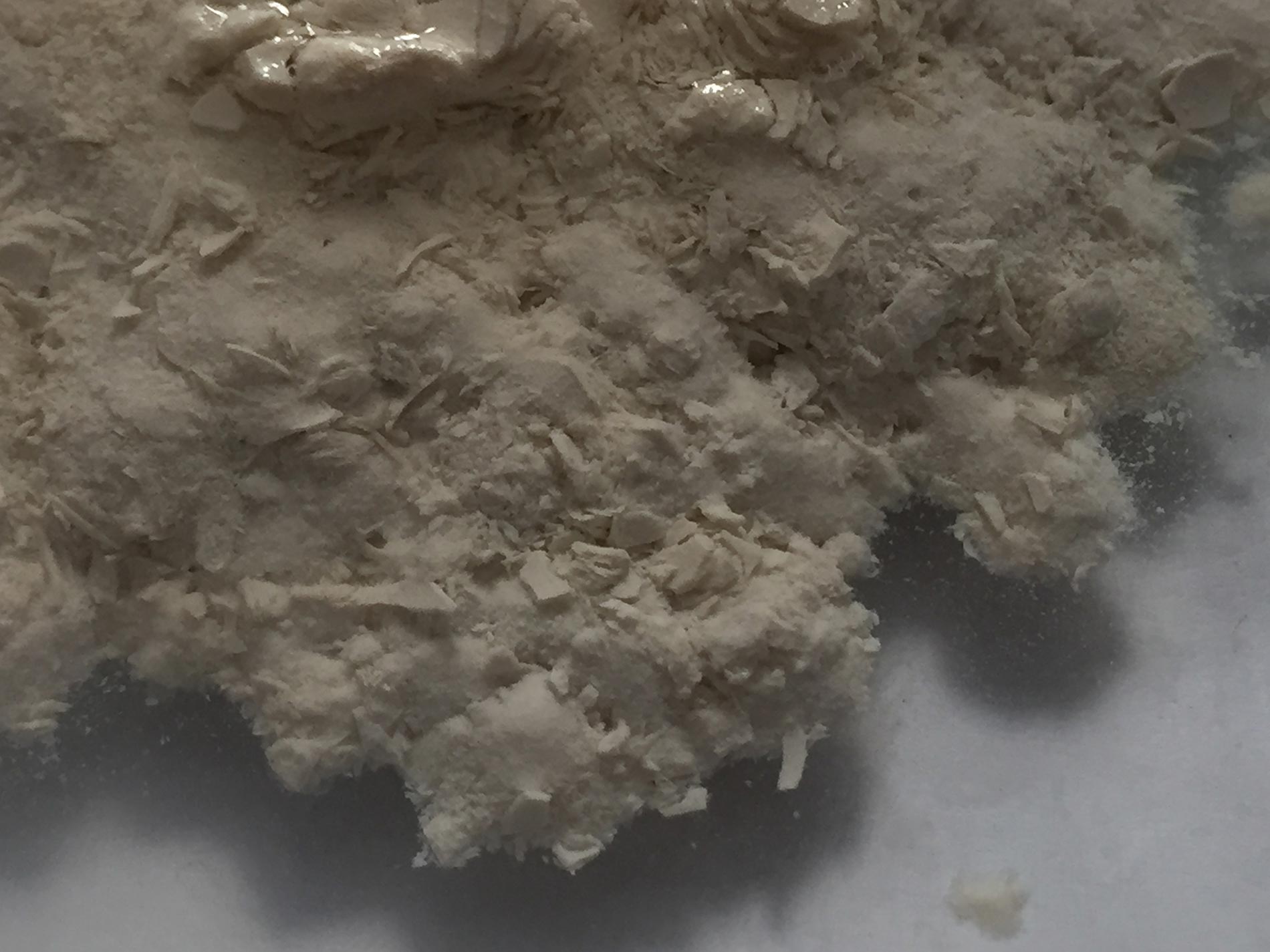

I laid down the ball of clay and spontaneously picked up my phone to take a picture. It went off with a sudden flash. In my photo reel, I found a pleasant surprise. The flash made the clay at rest and its marks on the worktop appear flattened. The image had all the beauty and layered texture of a 2D paper collage. That’s when I knew I had something: a study in ceramics, removed from all context of production.

For the group show in September, I presented a series of these collage-like images of clay, accompanied by audio and video recordings of micro-events from the studio – the pottery wheel in motion, the clay mixer churning. In the traces of making and doing, I had found my thesis. I was an explorer in my own world.

Click here to watch the video.

This rhythmic movement, the familiar prelude to making pottery, calms my busy mind in a way that staring at a blank screen or a blank canvas never can.

by pascale girardin photography by stephany hildebrand

Personal growth sometimes means taking “dramatic” risks.

Whether in the education system or in everyday life, the academic mindset involves learning new skills and pushing yourself outside your comfort zone. For me, the annual forum for Fine Arts masters students was the event that sent me careening into uncharted territory.

The premise of the showcase is simple: Students present the advancement of their work via PowerPoint presentations for discussion with the class. But art school being art school, some students questioned this status quo. My working group, titled Gestes (Gestures), comprised mostly of performance artists, felt the presentation format didn’t fit our practices. We unanimously decided to skip the body-of-work slides in favour of using our actual bodies. The group was pleased. I wondered what I’d gotten myself into.

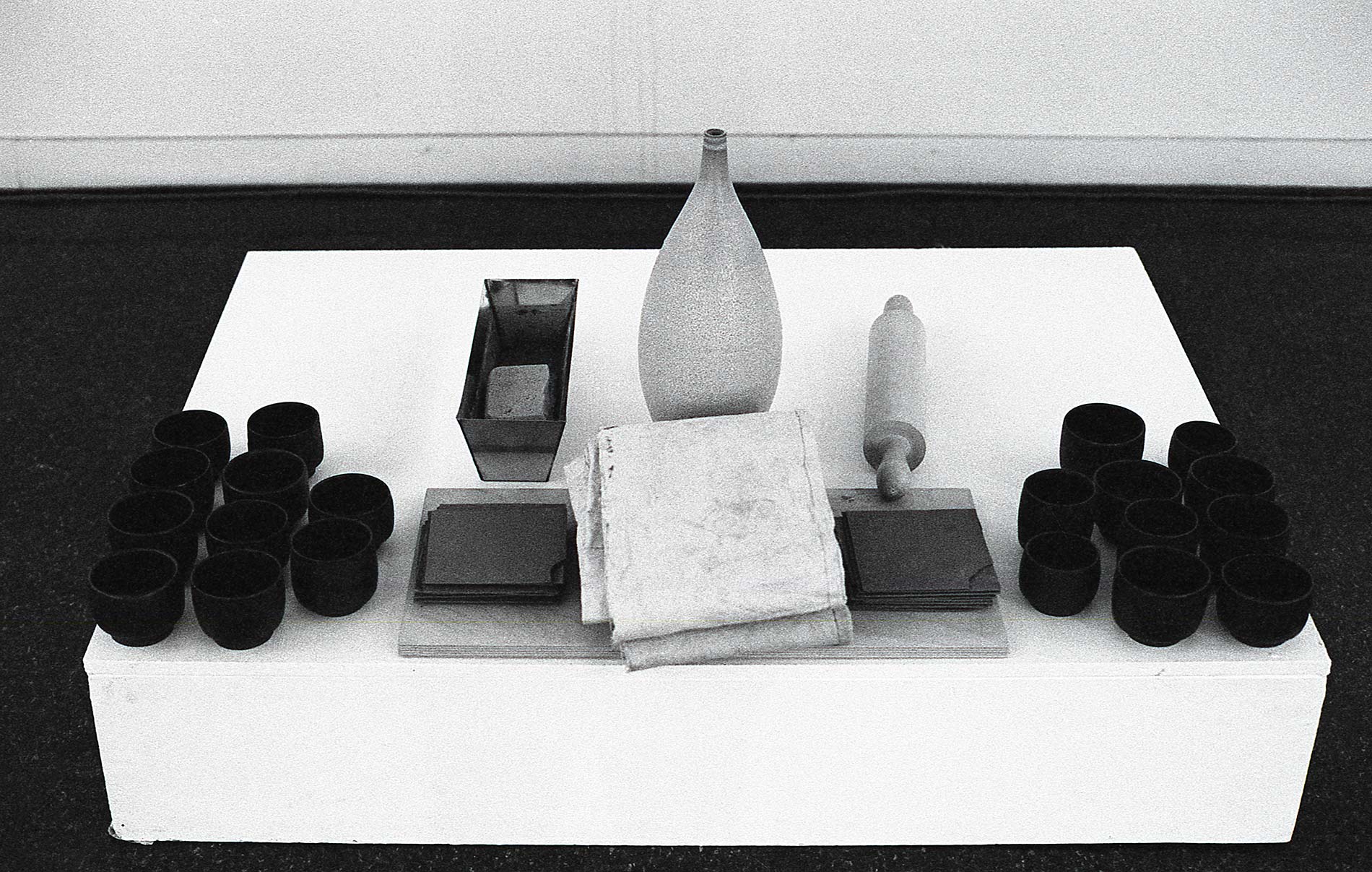

On the day of the presentation, I was nervous as I performed what would be my very first performance-art piece. While an audio recording played my verbal ruminations about a ceramic tea bowl, I set a cloth on the ground and laid it with a set of the same tea bowls atop small square saucers made of dried clay. The bowls were filled with water and served to the audience. As they drank and handled the bowls, experiencing for themselves the sensations conveyed in the audio recording, I assembled the squares and crushed them in the cloth. I then recollected the dry clay crumbs into a container, folded the canvas neatly and placed it behind me, remaining very still as the recording came to an end.

Taken apart, these gestures are known to me. They are ritual in ceramic work. New to me was performing them before an audience. Did it make a statement? Yes. Was it nerve-wracking? Absolutely! Fortunately, my initial fear was soon rewarded when classmates approached me to say they were moved by my piece.

Academia provides us the opportunity to experiment and take risks, but I believe that setting personal challenges should never cease. What is one thing you dream of doing but are too scared to try? Perhaps you can make it your goal for this academic year. The thrill of the attempt often overshadows the fear.

Whether in the education system or in everyday life, the academic mindset involves learning new skills and pushing yourself outside your comfort zone.

by pascale girardin photos by stephany hildebrand and pascale girardin

Three books that heighten the senses.

I’ve read exhaustively about creativity and specifically how our senses inform it. These three works on my bookshelf right now are eye- (and ear-) opening examinations of the ways we connect with and process the world around us.

La terre et les rêveries de la volonté (Earth and Reveries of Will, 1948)

In this seminal work, 20th-century French philosopher Gaston Bachelard looks into that mysterious form of consciousness we call daydreaming. He seeks to define and distinguish it from other dream states. Sleep dreams, he says, follow a narrative, whereas daydreams are a voyage of the mind in which thoughts meander through our actions and permit us to develop awareness. He studies the conditions that produce daydreams, such as staring into a fire or sinking one’s hands into soft textures, such as dough (or clay!) or a cat’s belly. It’s fascinating to follow along as Bachelard’s great mind unravels the everyday, asking difficult questions about what these overlooked states of being within the material world mean to the experience of living.

Making: Anthropology, Archeology, Art and Architecture (2013)

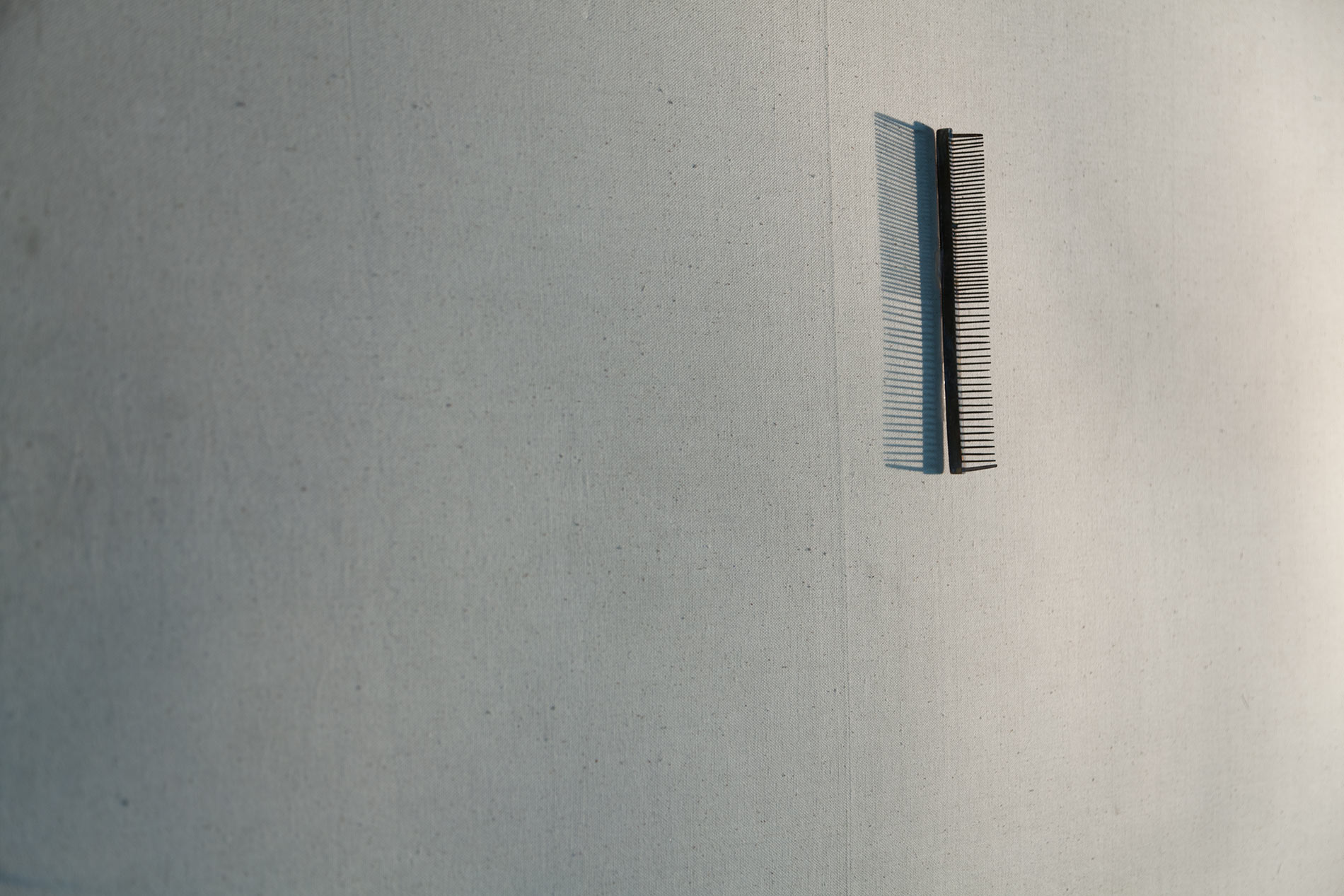

Author Tim Ingold is a social anthropologist. His book examines what our senses tell us when we make things and how the act of making, in turn, shapes us. In one revealing instance, he meticulously describes sawing through a plank of wood, going into vivid detail about how the grain feels below his fingertips, how his hand grips the saw’s handle, how its teeth slice into the wood. In another scene, he looks at a centuries-old comb describing the historic circumstances that led to the evolution of the tool, connecting the dots between object, maker and user. His writing presents a fascinating view of everyday objects in their historical and social contexts – and, once you’ve seen the world through his eyes, you will never look at it the same way again.

Silence: Lectures and Writings (1961)

John Cage is a composer and music philosopher. He’s perhaps best known for his 1952 recording 4‘33” in which he sat before a piano for four minutes and 33 seconds without playing a note. The piece made audiences question the notion of silence, for, even in the absence of music, ambient noise abounded. His avant-garde work also relied on the Chinese I Ching divination method to create musical scores. Cage’s first and most influential book, Silence, explores all aspects of sound: What we perceive as pleasant and unpleasant; why the spaces between sounds in music are as important as the music itself; how prose can be made to mimic music’s rhythmic structure. This book elevates our awareness of sound and sheds light on the power it wields over our existence.

by pascale Girardin main photograph courtesy of anton reijnders photography by pascale girardin

Dutch ceramicist Anton Reijnders interprets meaning through creation.

Anton Reijnders’s work exhibits the quality that ancient Greek philosophers called poiesis. The term describes bringing something into being that did not exist before – even in thought. The Dutch installation artist and founder of the European Ceramic Work Centre creates his pieces, which combine clay forms with wood, metal and other materials, not by drafting a plan of the outcome, but by allowing new meanings to unfold as he creates, and long after the artworks are completed.

Reijnders’s work brings together what he calls “old acquaintances” – recurring forms reproduced through slipcasting methods and his “made-ready-mades,” unique hand-built elements such as stacks of clay slabs or large, amphora-like vases – that produce connections with the viewers and between the pieces themselves. In this way he strives to make sense of the world through material, method and time.

I had the privilege of taking a master class with Reijnders this fall in Burlington, Ontario. In it, he guided us through a series of explorations aimed at challenging our visual preconceptions: Why do we call a thing beautiful versus ugly? How is our sense of observation informed by what we “think is there” rather than what is really in front of us? For the creator, Reijnders says, remaining open, alert and responsive to an artwork’s elements should continue long after an artwork is finalized. It’s how we find new meanings and continue to be engaged in making and experiencing art.

Perhaps it’s fitting that I left his session with more questions than answers. In Reijnders’s approach, that’s the best thing that can happen to an artist.

Creativity is linked to our ability to be open to opportunities that reach beyond a projected outcome. This distinguishes creation from production.

by pascale Girardin photography by stephany hildebrand

The three simple tenets that our workshop team lives by.

I may be a student myself but, to my studio staff, I am a teacher. The three most important lessons I impart, can be applied to all things we do.

Presence

The craft of ceramics requires sensitivity at the fingertips. I often say, “You must develop eyesight on the tips of your fingers. You need to re-learn the sense of touch.” I encourage my staff to spend time watching how their hand settles into states of soft or hard. To create something beautiful, you must be present to sensation. Ceramics is not just about making clay, it’s a complete discipline that should heighten awareness of the self.

Cleanliness

Our work is all about the art of preparation. Every evening the team cleans the studio with a mop and squeegee, so that we can begin each day anew. That means clean water, clean sponges, a clean table and a clean floor. We wash down the studio as a way of purifying our minds, so that when the physical body encounters clay, it knows where it’s going. When we see the finished piece, it is against an immaculate backdrop where it can be appreciated.

Elegance

Elegance, to me, is very simple: How do you get to where you want to go as effortlessly as possible, while eliminating all superfluous gestures? The opposite of elegance is what we call in French “la maladresse” or gracelessness, which creates a look of distress and confusion. Elegance requires restraint, thinking ahead and preparing the mind and body to perform a task. The result is a beautiful piece crafted with just the right amount of effort. No more, no less.

N° 2

Renewal

July/August 2017

BY PASCALE GIRARDIN PHOTOGRAPHY BY STEPHANY HILDEBRAND

This issue, our theme is renewal, the act of taking something old and making it new again.

It might be physical renewal like the way my friend and mentor Kinya Ishikawa is transforming broken shards of pottery into a monumental building or it may be an intangible such as how, with a shift in perspective, I came to see a failed studio experiment as a new direction in my craft. We also look to Japan as the source of spiritual concepts around the recycling and revitalisation of everyday objects.

“Drift” is my way of explaining how meandering thoughts can crystallize into a fully formed idea. This is origin of creativity and my mantra for daily life.

I invite you to drift with me.

Pascale Girardin

“Drift” is my way of explaining how meandering thoughts can crystallize into a fully formed idea. This is origin of creativity and my mantra for daily life.

by pascale girardin photography by stephany hildebrand

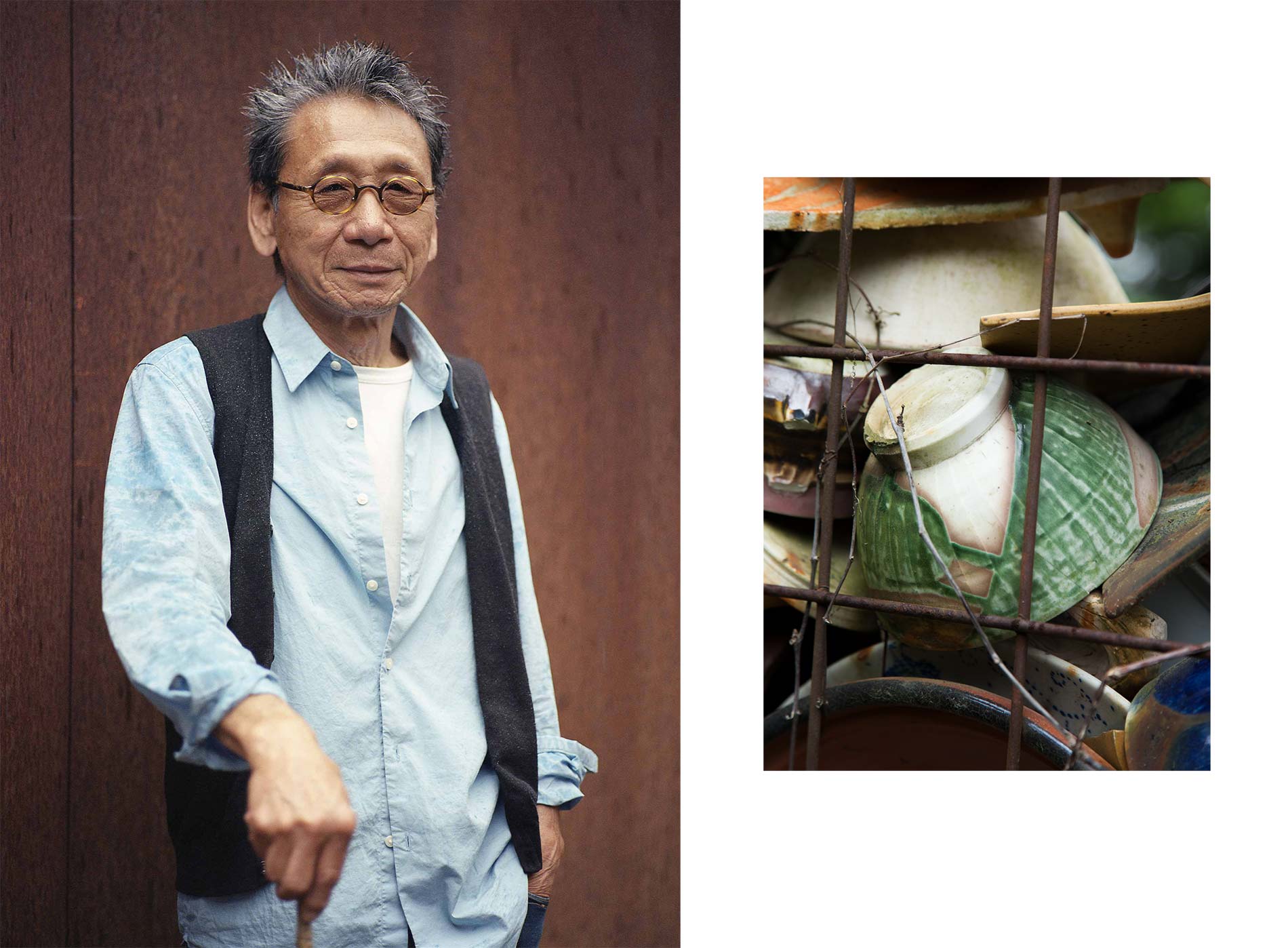

Kinya Ishikawa’s tribute to pottery is a structure unlike any other.

On his property in Val-David, Quebec, Kinya Ishikawa is building what I like to call a cathedral. Here, the walls are not bricks and mortar, but broken pieces of pottery, and it’s not a monument to the celestial divine, but to objects made by human hands.

Ishikawa is a self-taught potter who, for the last 20 years, has been my mentor. A former member of the Japanese bobsledding team, he came to Canada after the 1969 Bobsleigh World Cup, fell in love with the province of Quebec and never left. Though he spoke almost no English or French, he found a job cleaning a Montreal pottery studio in exchange for room and board and, after taking an interest in the craft, convinced the owner to let him wheel throw at night. From this humble background, Ishikawa developed into one of the province’s foremost potters.

Now in his 70s, he remains a prolific artist, while using his home in the Laurentian Mountains as a gathering place for the ceramics community. Since 1989, Ishikawa has hosted 1001 Pots (July 7 to August 13, 2017), a month-long pottery fair featuring the work of more than 100 studios. The unique format of open tables with a central cashier allows visitors to engage directly with the work. They can also chat with a roving crew of participating potters who each volunteer four days a year as docents to the event.

As for his cathedral, it’s called Jardin de silice (Silica Garden): a multi-chambered structure constructed by filling a double-walled metal framework with fragments of pottery – both his own and those of the visiting artists. Over time tree branches and vines have intertwined with the clay-filled partitions, making them truly live and breathe. It is an enchanting representation of Kinya’s passion for his life’s work.

Throughout the year, I save up my studio shards just for the Jardin de silice. Not only does it reduce waste, but it’s far easier to get over the loss of an over-fired sculpture or accidentally dropped vase knowing that they are going somewhere so beautiful.

by pascale girardin photography by pascale girardin

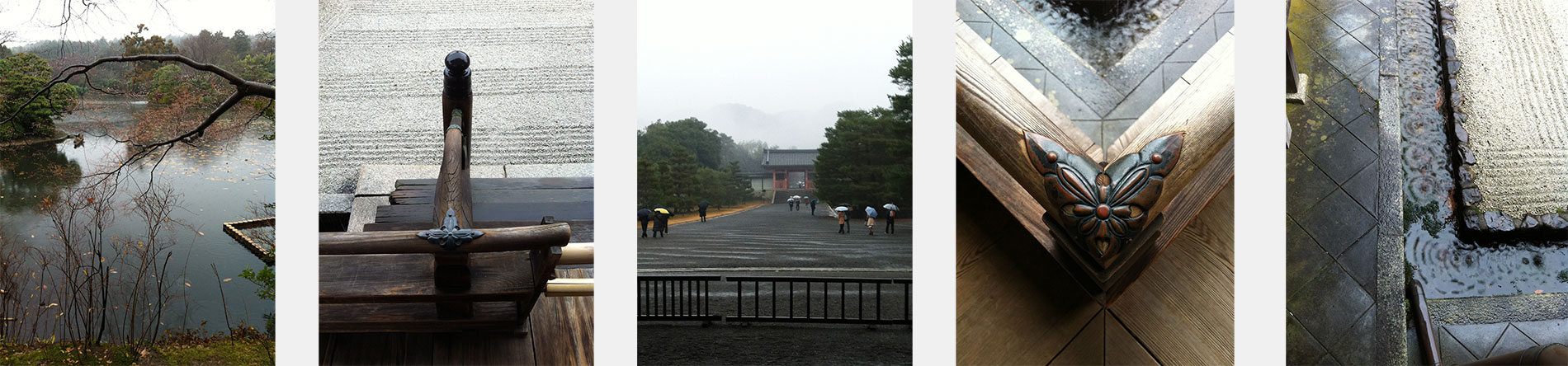

A journey to Japan reveals the poignant beauty of impermanence.

I once spent five days in Kyoto between Christmas and New Year. This is a period of renewal in which the Japanese clean their homes to begin the new year afresh. The shops were closed and many residents had left the city for the holidays, so I spent my time at the only places open: the temples.

At Ryōan-ji, a site famous for its Zen garden, five centuries of caretakers have drawn their wooden rakes over the garden’s pebbled sand, creating a fresh imprint, while simultaneously imparting a patina that deepens with age.

In Zen Buddhism, such transformations over time are what give objects their beauty. Well-worn things are revered in Japan and the act of renewing them has been elevated to an art form. We see it in the boro technique of reworking old fabrics into vibrant patchwork textiles, and in kintsugi, the practice of mending broken pottery with seams of silver and gold.

As an artist, I had studied and believed I understood the philosophy that the Japanese call mono no aware, which translates loosely as “empathy towards things.” But I was perhaps not prepared to see it enacted in the smallest ways. At one temple, I came across a stand of centuries-old trees, their knotted branches protruding at gravity-defying angles. But rather than cutting back the vulnerable appendages or simply allowing them to break off, the temple’s landscapers had instead bound the branches with sinew and propped them up on wooden crutches. It was moving to see these trees being cared for like an elderly person. A little TLC allowed them to thrive anew.

by pascale girardin photography by stephany hildebrand

Installations in the new Nobu Downtown take their cues from ancient Japanese craftwork.

In May, I had the great pleasure of dining in the private Sake Room of New York’s Nobu Downtown on a Japanese-fusion feast that included chef Nobu Matsuhisa’s exquisitely prepared yellowtail sashimi, wagyu gyoza and caramel soba cha bar. But this was no ordinary business dinner, for I was not only surrounded by members of my talented Montreal studio team but also by more than 70 custom sake bottles that we had created just for this intimate dining space.

The newly opened Nobu Downtown symbolizes renewal in every sense. First, it’s the result of a more than two-decade-old partnership between Robert De Niro and Matsuhisa: the actor discovered the chef in Los Angeles and convinced him to establish his first Nobu in New York’s Tribeca neighborhood in 1993. And because Downtown will now succeed Tribeca as the NYC flagship, it also marks a full-circle collaboration between Matsuhisa and David Rockwell. The world-renowned designer of the original Nobu went on to conceptualize more than 30 of the star chef’s restaurants internationally.

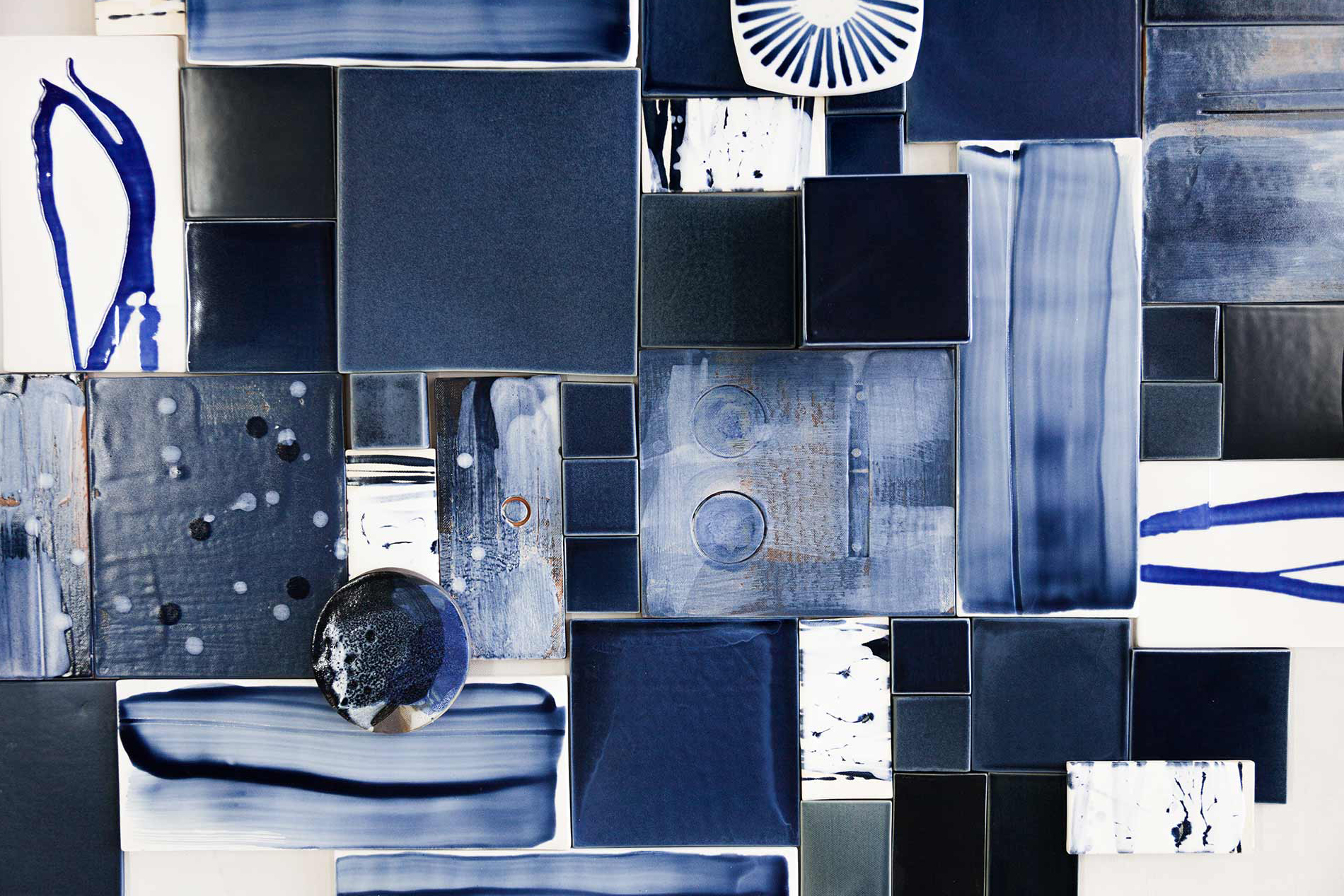

I was invited by Rockwell Group to create the Sake Room “walls” – two floor-to-ceiling shelving units lined with individually painted earthenware vessels – as well as two other site-specific installations. One is a mural of blue-glazed tiles and blocks that demarcates the private dining area. The other is an installation spread over two Venetian plaster walls. Made up of more than 3,500 individual ceramic elements, from up close, it resembles charred wood briquettes; from afar, it appears as two giant brush strokes.

The three works were influenced by the Japanese ink-brush painting style known as sumi-e. The ancient practice is a central theme in Rockwell’s design and appears throughout the 12,500-square-foot space from the black accents on the restaurant’s votive light fixtures to a suspended installation by New York artist John Houshmand that resembles floating lines of ink. To dine, as we did, in this place where timeless art forms meet thoroughly modern design is quite possibly as divine as, well, a bite of Nobu’s famous black cod with miso.

by pascale girardin photography by stephany hildebrand

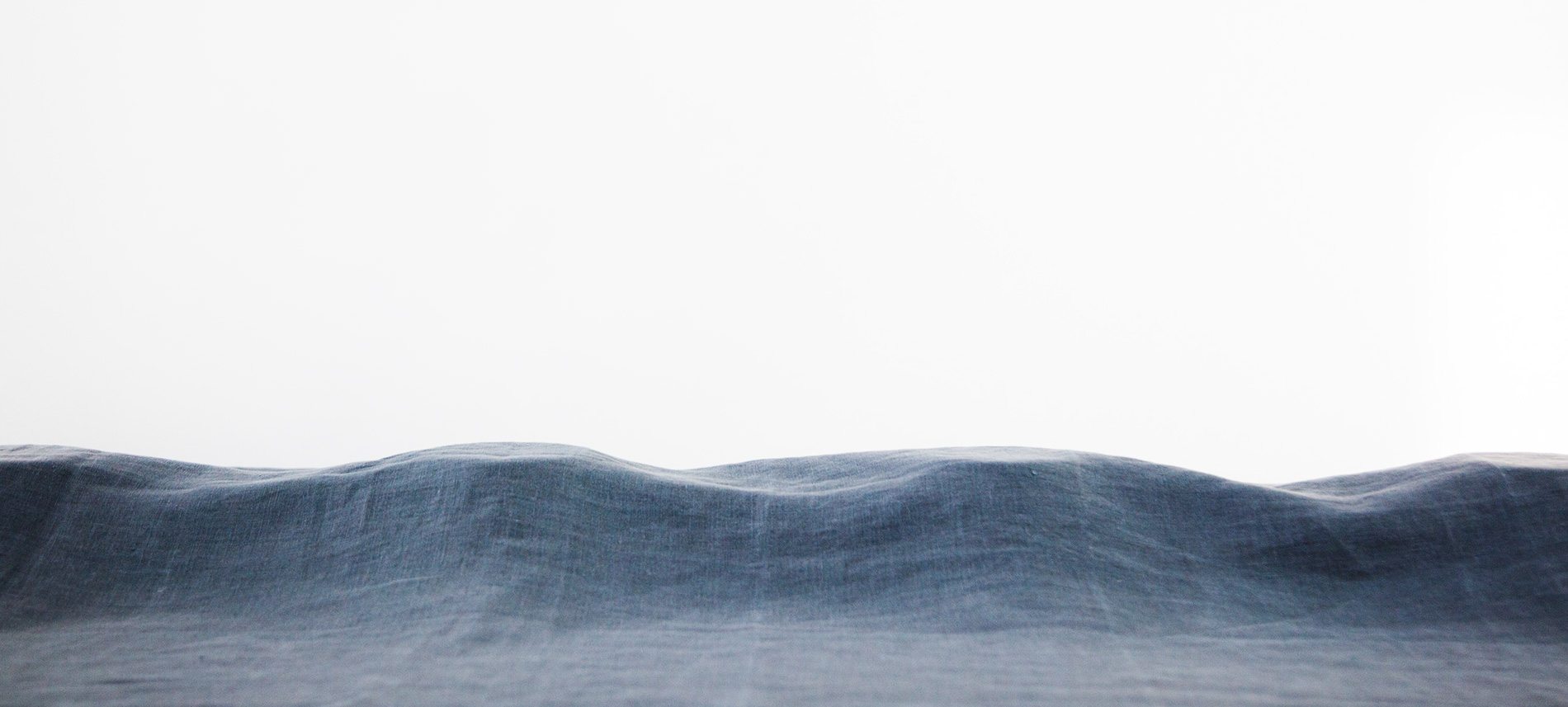

A look at the technique behind Japanese boro textiles.

Until I Googled “Japanese indigo patchwork,” I had yet to learn the name of the vibrant textile style that I’d become so enamored with on my travels to Tokyo and Kyoto. The technique I now know as boro is a folk art born out of the practical desire to extend the life of worn, but still useable, cloth.

What most struck me about the technique was that, unlike Western quilting that makes use of symmetrical squares and patterns, boro uses panels of irregular shapes and sizes, which gives the patchwork a lively quality.

Natural indigo dyes are regularly present in the stitched-together fabrics. In fact, the colour blue is quite often the only thing that the panels – each one its own vibrant pattern of stripes, checks or stylized botanical designs – have in common.

I felt a special kinship with these textiles because cobalt makes a frequent appearance in my own work and I’ve spent years formulating my own special blends of blue glazes. So, when given the extraordinary opportunity to design a unique feature wall for New York’s Nobu Downtown, boro textiles provided the inspiration.

Combining ceramic tiles and blocks in three different blue glazes that further permutated with their placement in the kiln, the result is a two- and three-dimensional “patchwork.” The wall is additionally brought to life with LED votives, whose fixtures are concealed within the installation. It’s delightful that, gracing the walls of one of Manhattan’s most illustrious restaurants, you can now find this homage to a little-known household craft from half a world away.

by pascale girardin photography by ginga takeshima and stephany hildebrand

A shift in perspective results in the birth of the Totem sculptures.

In the last few years, my Totem sculptures have become an integral part of my work. The pieces are created by stacking several ceramic elements of different shapes, sizes and forms into a textural column. They are cathartic pieces for me because, unlike the very precise work that is required for my installations, I create the totems by intuition and feel.

Each of the totemic elements begins as an idea for an individual piece, created to exist on its own. But, sometimes, when it is unloaded from the kiln, the piece produced doesn’t meet my expectations and I’m not quite sure what to make of it. That’s when I place it on a shelf or in a cupboard somewhere – away, but still in my field of vision.

Zen Buddhist reflections on art teach us that if we abandon our notions of what a thing is supposed to be, we can appreciate it for what it is. I’ve learned that I need to tuck these pieces away and wait until I’m ready for them (rather than them being ready for me). Finally, after a gestation period of days, weeks or months, a piece will suddenly reveal itself. I’ll make connections that I hadn’t made before. A Totem is formed.

Today I see my studio shelves as an endless source of discovery. One needs to have faith in their own curiosity and openness to chance. Rather than discarding an idea, I now give myself the time to reclaim it.

Zen Buddhist reflections on art teach us that if we abandon our notions of what a thing is supposed to be, we can appreciate it for what it is.

N° 1

Head Space

May/June 2017

By Pascale Girardin Photography by Stephany Hildebrand

Ideas and inspiration from the studio of Pascale Girardin

Welcome to the first issue of Drift. This bi-monthly magazine looks at my work and inspirations. The idea came from visiting designers who would often get just as excited about the personal snapshots they saw on my iPhone – studio samples, a clay bust made in a friend’s barn, an antique spoon collection – as they would about the ceramic pieces I was in their offices to present.

“Drift” is my metaphor for the creative thought process. It’s how I translate, from my native French, the word errance, which means wandering. It implies that one has erred, maybe taken the long way around or made a wrong turn, but that the result is a new discovery.

Similarly, creative inspiration doesn’t come to us in a linear way. Instead, seemingly disparate influences (like the contents of my iPhone) will suddenly coalesce into one fully formed idea. We have only to allow ourselves the mental time and space to see it. In that way, Drift is an ode to meandering. It’s about setting the mind free to find the surprising connections that we make when we let our thoughts wander. We’ll explore this topic in this issue and, in every issue, a new theme that connects the loose dots between my work and its inspirations.

I invite you to drift with me.

Pascale Girardin

Drift is about setting the mind free to find the surprising connections that we make when we let our thoughts wander.

A detour through Montreal’s ruelles offers an insider view of the city.

In my early 20s, I backpacked across the United States for two years. This was before email, mobile phones and couchsurfing.com, when you showed up in a new place, called someone from a payphone and said things like, “Hi, this is Jim’s friend. Did you get my letter?” When I returned home to Montreal, I continued to take the road less travelled, quite literally by choosing to always walk in alleyways instead of on the main streets. Our alleys, or ruelles, are not what you might imagine when you think of urban side streets. Montreal apartment buildings have no front yards, so life happens out back. Residents take a genuine pride in these spaces, cleaning and decorating them. They block the alley from cars (respectfully sending out notices with the date and time) to hold street parties and let their kids trick-or-treat in safety. In some cases, the whole neighbourhood agrees to close the alley permanently, turning it into a green space, or ruelle verte.

Sometimes, between the latticework of fences, you’ll peek into backyards and see flowers blossoming or people having a barbeque. But more often than not, the alleys are quiet and you’re more likely to run into a cat than a human. The ruelles are places of retrospection amidst the commotion of urban life and provide a new perspective on one’s journey from Point A to Point B. Even today, as I stroll through these byways, I know my inner backpacker would approve.

A Chinese ceramics town provides the muse for a Harry Winston vitrine and a lesson about the power of travel.

As a French Canadian, raised in America, who later settled back in Canada, my younger life was a constant search for identity. How do you answer the question “Where are you from?” when your nationality of passport and of culture are different? The same is true in my work. People often ask me about the form of my totem sculptures: Are they African drum or Asian vase? The answer is that they are both and neither.

A few years ago, I stumbled upon the concept of Third Culture Kids (TCKs). It’s a term that covers the children of military personnel, diplomats, missionaries and, as in my case, academics working abroad. Research showed that, instead of being damaged by the frequent changes experienced in childhood, TCKs actually grew into highly adaptive adults.

Once I had a name for my tribe of nomads, the questions about my identity were replaced with a sense of freedom. I could be an eternal tourist in my own life.

I happened to be in Jingdezhen, “China’s porcelain capital,” where I’d been particularly taken with the local technique for ceramic flowers, when I received a call from the artistic director of Harry Winston. She wanted an installation for the brand’s vitrines around the world to mark the launch of its Sunflower collection. I rushed back to the workshop district, known as The Sculpture Factory, and started an intensive training in the Jingdezhen flower-making tradition – Chinese petals for an American jeweller.

The experience was part serendipity, part observation from the fresh eyes of a stranger. Travel sharpens us in so many ways, from honing our curiosity to spotting the opportunities that are right in front of us. That’s true for everyone – no TCK status required.

Photography by Gabriel Orozco Astroturf Constellation, 2012 Inkjet print 44 x 54 inches Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Gift of the artist, 2013 2012.119.13

This month’s featured artist, Gabriel Orozco, shows us the parallels between otherwise unconnected found objects.

Gabriel Orozco is an artist who embodies this issue’s theme of “drift”: the creative meandering that happens before a fully formed idea is realized. To create Astroturf Constellation (2012), the Mexican-born, Tokyo-based sculptor visited a soccer field in New York to assemble and take pictures of the trash left behind by spectators after a game. Later, he combined the objects – candy wrappers, bits of soccer balls, shoelaces, plastic – into an installation, turning the unwanted remnants into a work of art.

Likewise, for his piece Sandstars (2012), he collected the detritus washed up on the shores of Isla Arena, Mexico, and organized it according to size and colour, making visual connections between the seemingly unconnectable. He summed up this thinking in an interview with Artforum: “When you put together a group of objects, regardless of their origin, you form a constellation: a group of associations that somehow belongs to you.”

More recently, the artist has taken his constellation philosophy out of the gallery and into the design of public space. His courtyard garden for the U.K.’s South London Gallery opened this January. The six-year project involved laying thousands of stones in spiralling patterns around botanical features. Visitors can appreciate in the work at ground level by tracing its meditative circular footpaths, or take in its entierty from the gallery’s upper-floor windows. Now, rather than picking up the unwanted, Orozco is laying down the beautiful.

A summer vacation in an old barn gives rise to a new series of busts.

It’s so interesting to see where your mind goes when you make something just for yourself. Last summer, my friends Nancy and Frank gave me free reign of their barn at The Wilfrid Farmhouse, an inn in Prince Edward County, Ontario. This was my vacation, a break from the studio and my fine-art masters’ studies.

Their barn is full of antique hardware left over from its more than 100 years as a working farm. It’s also home to the couple’s egg-laying hens, who pecked around my feet as I laid down an old door to serve as my worktable.

The country setting got me thinking about the folk-art tradition and its craftspeople – average folks who did beautiful work from their kitchen tables and front porches but weren’t trying to make something considered high art. For some time, I had been making little porcelain doll heads in a folk-art style and, under the influence of the barn, grew the idea into a series of busts.

The work I do for my masters is very introspective and all of it must be backed by research. These heads proved its antithesis: They were figurative pieces with no thought behind them. I came back from the farm, energized, and partially glazed them in blue. Now they look like something medieval, as though wearing a helmet or veil.

I love these pieces: There’s something so raw and pure about them, the result of that impulse to reach into myself and create like a child. In that barn, I learned that sometimes creativity requires you to think like the folk artist, removing all the social layers and going straight to basics, to the core element of what we are, outside of culture and time.

Sometimes creativity requires removing all the social layers and going straight to basics, to the core element of what we are, outside of culture and time.