N° 2

Renewal

July/August 2017

BY PASCALE GIRARDIN PHOTOGRAPHY BY STEPHANY HILDEBRAND

This issue, our theme is renewal, the act of taking something old and making it new again.

It might be physical renewal like the way my friend and mentor Kinya Ishikawa is transforming broken shards of pottery into a monumental building or it may be an intangible such as how, with a shift in perspective, I came to see a failed studio experiment as a new direction in my craft. We also look to Japan as the source of spiritual concepts around the recycling and revitalisation of everyday objects.

“Drift” is my way of explaining how meandering thoughts can crystallize into a fully formed idea. This is origin of creativity and my mantra for daily life.

I invite you to drift with me.

Pascale Girardin

“Drift” is my way of explaining how meandering thoughts can crystallize into a fully formed idea. This is origin of creativity and my mantra for daily life.

by pascale girardin photography by stephany hildebrand

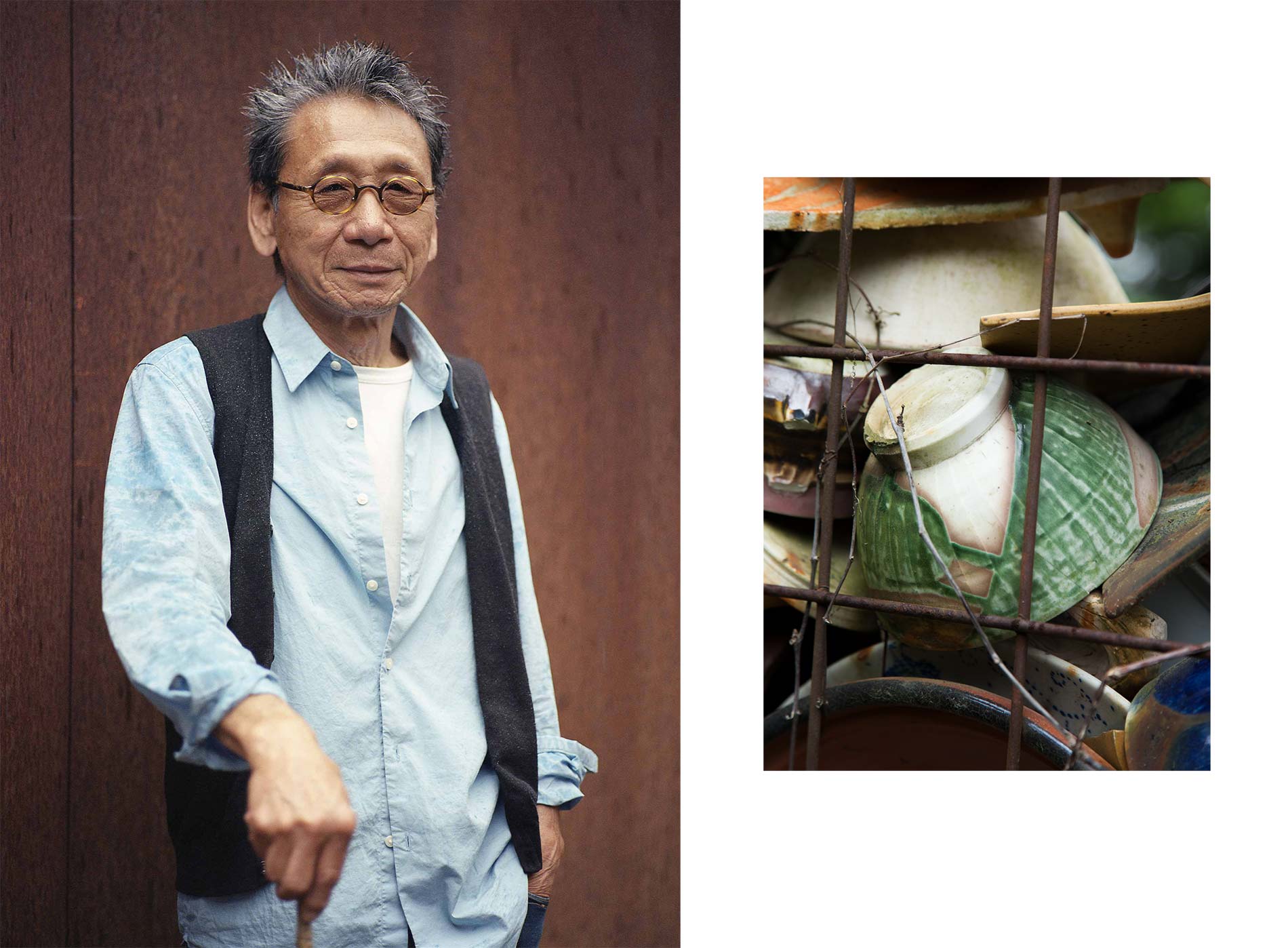

Kinya Ishikawa’s tribute to pottery is a structure unlike any other.

On his property in Val-David, Quebec, Kinya Ishikawa is building what I like to call a cathedral. Here, the walls are not bricks and mortar, but broken pieces of pottery, and it’s not a monument to the celestial divine, but to objects made by human hands.

Ishikawa is a self-taught potter who, for the last 20 years, has been my mentor. A former member of the Japanese bobsledding team, he came to Canada after the 1969 Bobsleigh World Cup, fell in love with the province of Quebec and never left. Though he spoke almost no English or French, he found a job cleaning a Montreal pottery studio in exchange for room and board and, after taking an interest in the craft, convinced the owner to let him wheel throw at night. From this humble background, Ishikawa developed into one of the province’s foremost potters.

Now in his 70s, he remains a prolific artist, while using his home in the Laurentian Mountains as a gathering place for the ceramics community. Since 1989, Ishikawa has hosted 1001 Pots (July 7 to August 13, 2017), a month-long pottery fair featuring the work of more than 100 studios. The unique format of open tables with a central cashier allows visitors to engage directly with the work. They can also chat with a roving crew of participating potters who each volunteer four days a year as docents to the event.

As for his cathedral, it’s called Jardin de silice (Silica Garden): a multi-chambered structure constructed by filling a double-walled metal framework with fragments of pottery – both his own and those of the visiting artists. Over time tree branches and vines have intertwined with the clay-filled partitions, making them truly live and breathe. It is an enchanting representation of Kinya’s passion for his life’s work.

Throughout the year, I save up my studio shards just for the Jardin de silice. Not only does it reduce waste, but it’s far easier to get over the loss of an over-fired sculpture or accidentally dropped vase knowing that they are going somewhere so beautiful.

by pascale girardin photography by pascale girardin

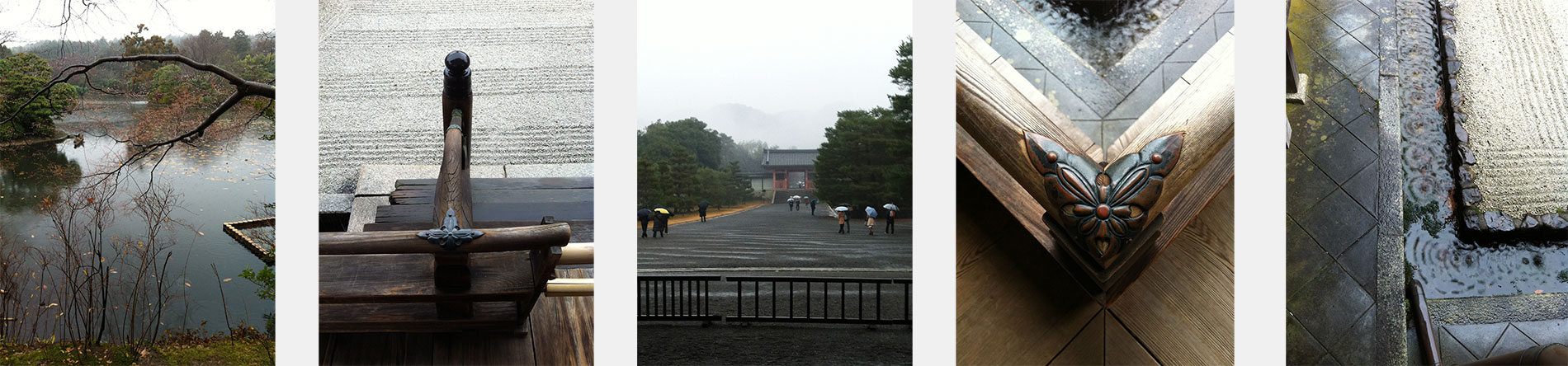

A journey to Japan reveals the poignant beauty of impermanence.

I once spent five days in Kyoto between Christmas and New Year. This is a period of renewal in which the Japanese clean their homes to begin the new year afresh. The shops were closed and many residents had left the city for the holidays, so I spent my time at the only places open: the temples.

At Ryōan-ji, a site famous for its Zen garden, five centuries of caretakers have drawn their wooden rakes over the garden’s pebbled sand, creating a fresh imprint, while simultaneously imparting a patina that deepens with age.

In Zen Buddhism, such transformations over time are what give objects their beauty. Well-worn things are revered in Japan and the act of renewing them has been elevated to an art form. We see it in the boro technique of reworking old fabrics into vibrant patchwork textiles, and in kintsugi, the practice of mending broken pottery with seams of silver and gold.

As an artist, I had studied and believed I understood the philosophy that the Japanese call mono no aware, which translates loosely as “empathy towards things.” But I was perhaps not prepared to see it enacted in the smallest ways. At one temple, I came across a stand of centuries-old trees, their knotted branches protruding at gravity-defying angles. But rather than cutting back the vulnerable appendages or simply allowing them to break off, the temple’s landscapers had instead bound the branches with sinew and propped them up on wooden crutches. It was moving to see these trees being cared for like an elderly person. A little TLC allowed them to thrive anew.

by pascale girardin photography by stephany hildebrand

Installations in the new Nobu Downtown take their cues from ancient Japanese craftwork.

In May, I had the great pleasure of dining in the private Sake Room of New York’s Nobu Downtown on a Japanese-fusion feast that included chef Nobu Matsuhisa’s exquisitely prepared yellowtail sashimi, wagyu gyoza and caramel soba cha bar. But this was no ordinary business dinner, for I was not only surrounded by members of my talented Montreal studio team but also by more than 70 custom sake bottles that we had created just for this intimate dining space.

The newly opened Nobu Downtown symbolizes renewal in every sense. First, it’s the result of a more than two-decade-old partnership between Robert De Niro and Matsuhisa: the actor discovered the chef in Los Angeles and convinced him to establish his first Nobu in New York’s Tribeca neighborhood in 1993. And because Downtown will now succeed Tribeca as the NYC flagship, it also marks a full-circle collaboration between Matsuhisa and David Rockwell. The world-renowned designer of the original Nobu went on to conceptualize more than 30 of the star chef’s restaurants internationally.

I was invited by Rockwell Group to create the Sake Room “walls” – two floor-to-ceiling shelving units lined with individually painted earthenware vessels – as well as two other site-specific installations. One is a mural of blue-glazed tiles and blocks that demarcates the private dining area. The other is an installation spread over two Venetian plaster walls. Made up of more than 3,500 individual ceramic elements, from up close, it resembles charred wood briquettes; from afar, it appears as two giant brush strokes.

The three works were influenced by the Japanese ink-brush painting style known as sumi-e. The ancient practice is a central theme in Rockwell’s design and appears throughout the 12,500-square-foot space from the black accents on the restaurant’s votive light fixtures to a suspended installation by New York artist John Houshmand that resembles floating lines of ink. To dine, as we did, in this place where timeless art forms meet thoroughly modern design is quite possibly as divine as, well, a bite of Nobu’s famous black cod with miso.

by pascale girardin photography by stephany hildebrand

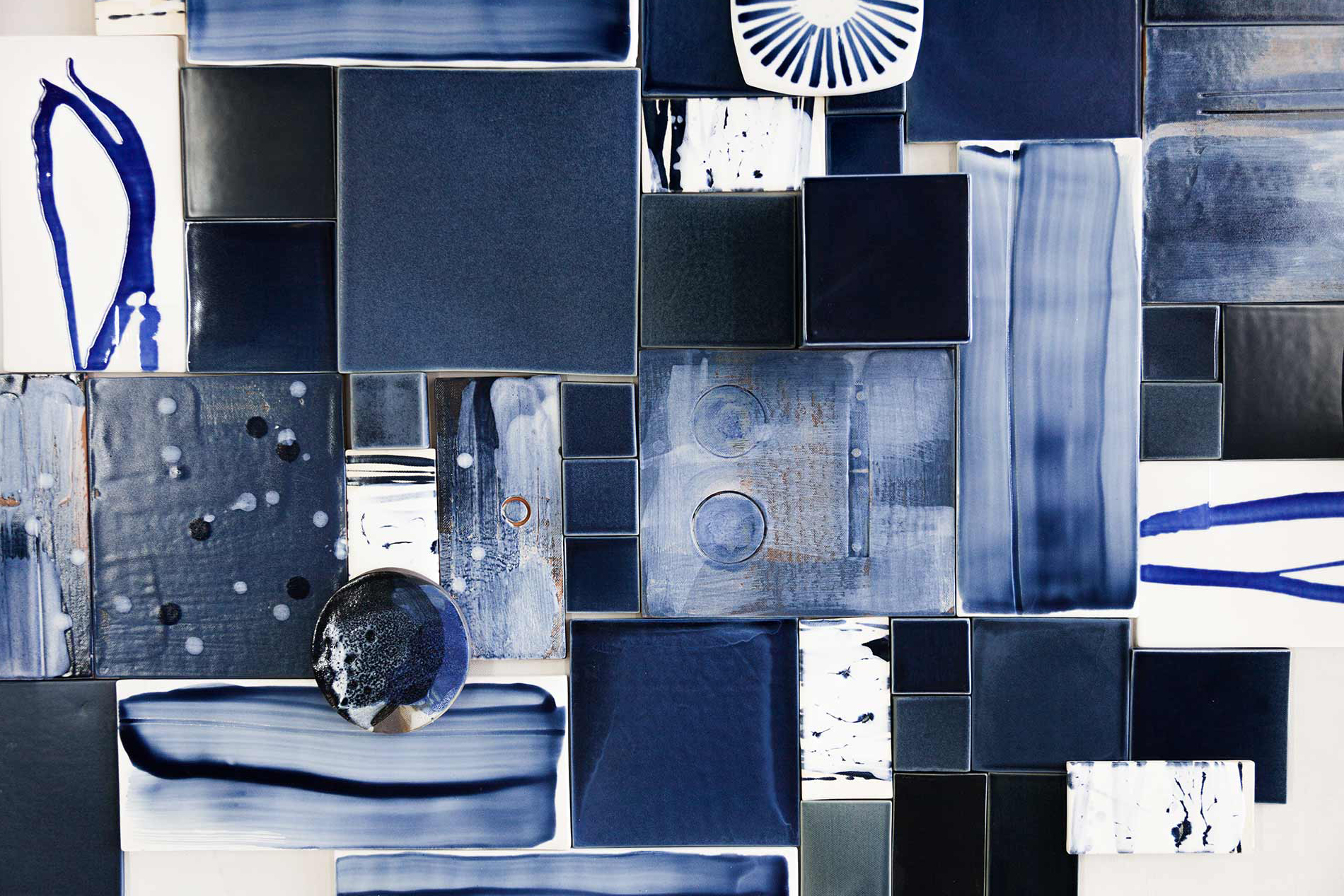

A look at the technique behind Japanese boro textiles.

Until I Googled “Japanese indigo patchwork,” I had yet to learn the name of the vibrant textile style that I’d become so enamored with on my travels to Tokyo and Kyoto. The technique I now know as boro is a folk art born out of the practical desire to extend the life of worn, but still useable, cloth.

What most struck me about the technique was that, unlike Western quilting that makes use of symmetrical squares and patterns, boro uses panels of irregular shapes and sizes, which gives the patchwork a lively quality.

Natural indigo dyes are regularly present in the stitched-together fabrics. In fact, the colour blue is quite often the only thing that the panels – each one its own vibrant pattern of stripes, checks or stylized botanical designs – have in common.

I felt a special kinship with these textiles because cobalt makes a frequent appearance in my own work and I’ve spent years formulating my own special blends of blue glazes. So, when given the extraordinary opportunity to design a unique feature wall for New York’s Nobu Downtown, boro textiles provided the inspiration.

Combining ceramic tiles and blocks in three different blue glazes that further permutated with their placement in the kiln, the result is a two- and three-dimensional “patchwork.” The wall is additionally brought to life with LED votives, whose fixtures are concealed within the installation. It’s delightful that, gracing the walls of one of Manhattan’s most illustrious restaurants, you can now find this homage to a little-known household craft from half a world away.

by pascale girardin photography by ginga takeshima and stephany hildebrand

A shift in perspective results in the birth of the Totem sculptures.

In the last few years, my Totem sculptures have become an integral part of my work. The pieces are created by stacking several ceramic elements of different shapes, sizes and forms into a textural column. They are cathartic pieces for me because, unlike the very precise work that is required for my installations, I create the totems by intuition and feel.

Each of the totemic elements begins as an idea for an individual piece, created to exist on its own. But, sometimes, when it is unloaded from the kiln, the piece produced doesn’t meet my expectations and I’m not quite sure what to make of it. That’s when I place it on a shelf or in a cupboard somewhere – away, but still in my field of vision.

Zen Buddhist reflections on art teach us that if we abandon our notions of what a thing is supposed to be, we can appreciate it for what it is. I’ve learned that I need to tuck these pieces away and wait until I’m ready for them (rather than them being ready for me). Finally, after a gestation period of days, weeks or months, a piece will suddenly reveal itself. I’ll make connections that I hadn’t made before. A Totem is formed.

Today I see my studio shelves as an endless source of discovery. One needs to have faith in their own curiosity and openness to chance. Rather than discarding an idea, I now give myself the time to reclaim it.

Zen Buddhist reflections on art teach us that if we abandon our notions of what a thing is supposed to be, we can appreciate it for what it is.