By Pascale girardin photography by Stephany Hildebrand

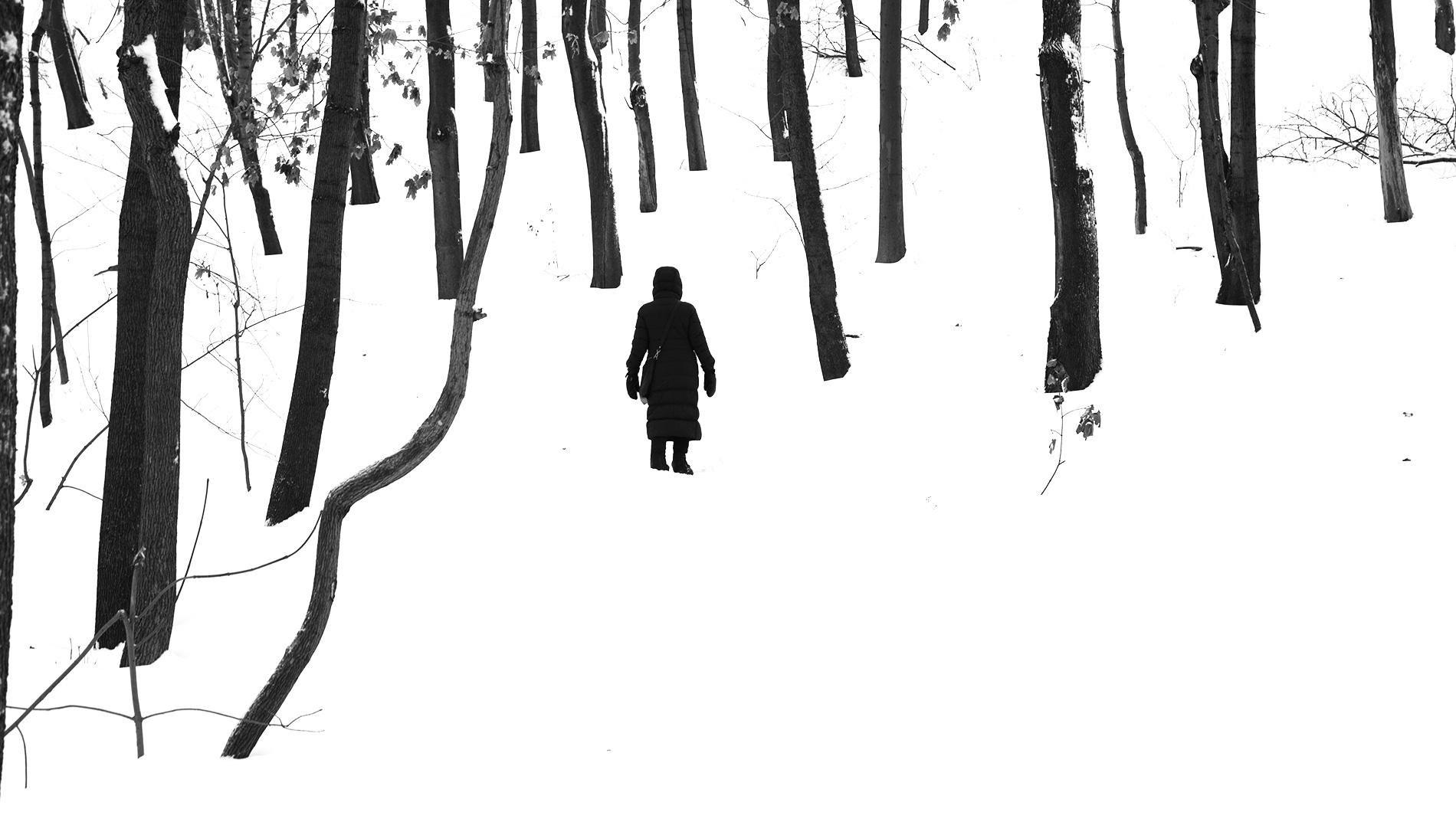

In Montreal, we get through winter by embracing it.

The city spends six months under a thick blanket of snow. To the uninitiated, it seems like a lifeless season. But explore it and you make discoveries, like how the dried golden field grasses that peek through the white landscape are still alive under the earth, waiting to turn green again in the spring. Or how, when you peer through a transparent patch of pond ice, you spot the bubbles of fish swimming just below the frozen surface.

This issue, we examine the notion of dormancy. We live in a time when activity has turned into a permanent state of being. We are expected to produce at lightning speed. I want, instead, to celebrate the uneventful. Dormancy means trusting that things are operating without any activation on our part.

“On Drying” looks at how, just as the ceramist must step back during the drying process, so should the mind be permitted times of dormancy to achieve its potential. “Scream at the Wall,” delves into an instruction manual by Yoko Ono for achieving… nothing. And “Unexpected Communion” reveals how the invisible elements of terroir shape a wine’s flavour in surprising ways.

“Drift” is my way of explaining how meandering thoughts can crystallize into a fully formed idea. It’s the origin of creative thinking and my mantra for daily life.

I invite you to drift with me.

Pascale Girardin

Dormancy means trusting that things are operating without any activation on our part.

By pascale Girardin Photography by Stephany Hildebrand

The transformative act of letting things be.

Patience is the first lesson of ceramics. Clay needs time to dry. It can take an hour for a bone china flower petal, or a few months for a thick-walled bench.

As clay dries, it shrinks by about 10 percent. A piece that begins at 100 centimetres, can compress by 10. We help that movement along by placing the object on smooth cotton so it can gently slide, obeying a natural law that we know happens, but is too subtle to see.

This property of clay gives us an analogy for other life cycles. As a painter, it took me 10 years to realize that I have a two-year pattern of production: six months of work and 18 months of having nothing to express. Had I not observed and allowed myself the time to make that connection, I could easily have given up, comparing myself to more productive artists.

Instead, something told me to be patient. During the quiet times I travelled, visited friends, took classes. It seemed the ideas would not come until they were ready for the canvas. When they did, each new painting series became a departure from the one before.

It’s taught me that we must not resist our downtimes. Like drying clay, they allow us to shift imperceptibly into a new stasis.

by pascale girardin Photos by stephany hildebrand

Inside Yoko Ono’s instruction manual for doing nothing.

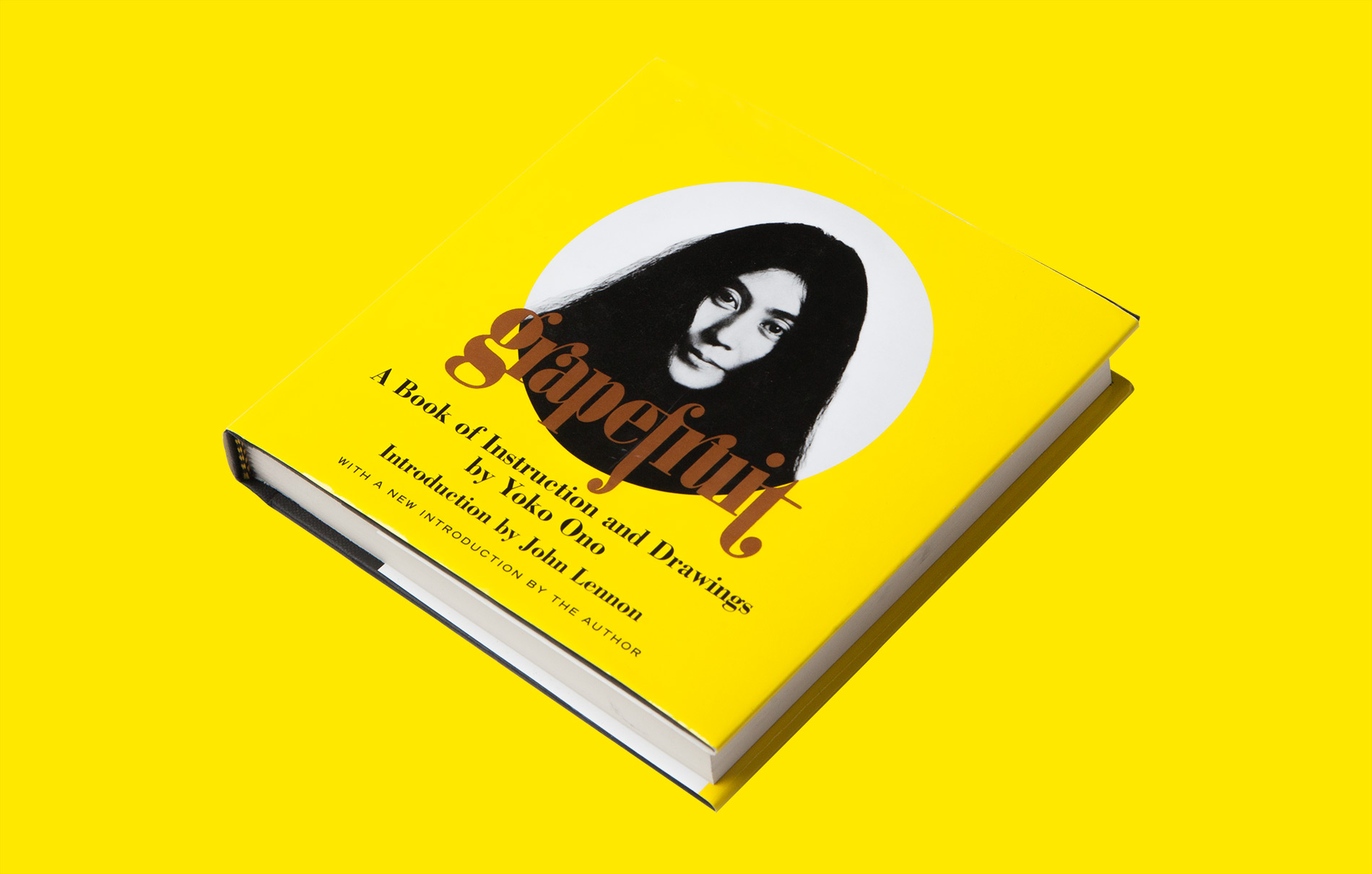

This issue’s theme of dormancy can be expressed as “Process” being both the means to an end and the end in itself. One of the most wonderful and illuminating books I’ve read on this idea is Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit: A Book of Instructions and Drawings. In it, Ono outlines dozens of directives for creating works of art.

Some can be easily executed…

Shadow Piece Put your shadows together until they become one. 1963

While others, less so…

Tape Piece I Take the sound of the stone aging. 1963 autumn/

And some combine a bit of both…

Stone Piece Find a stone that is your size or weight. Crack it until it becomes a fine powder. Dispose of it in the river. (a) Send small amounts to your friends. (b) Do not tell anybody what you did. Do not explain about the powder to the friends to whom you send. 1963 winter

I love this book because there is no result to these instructions, their actions lead nowhere and they don’t produce anything. Instead, they’re about giving life to experiences that are ours alone to delight in.

When people ask me what the most important thing is in life, I answer: ‘Just breathe.’

by Pascale Girardin Book courtesy of Domain Grivot

An evening in Burgundy reveals the definition of wine terroir.

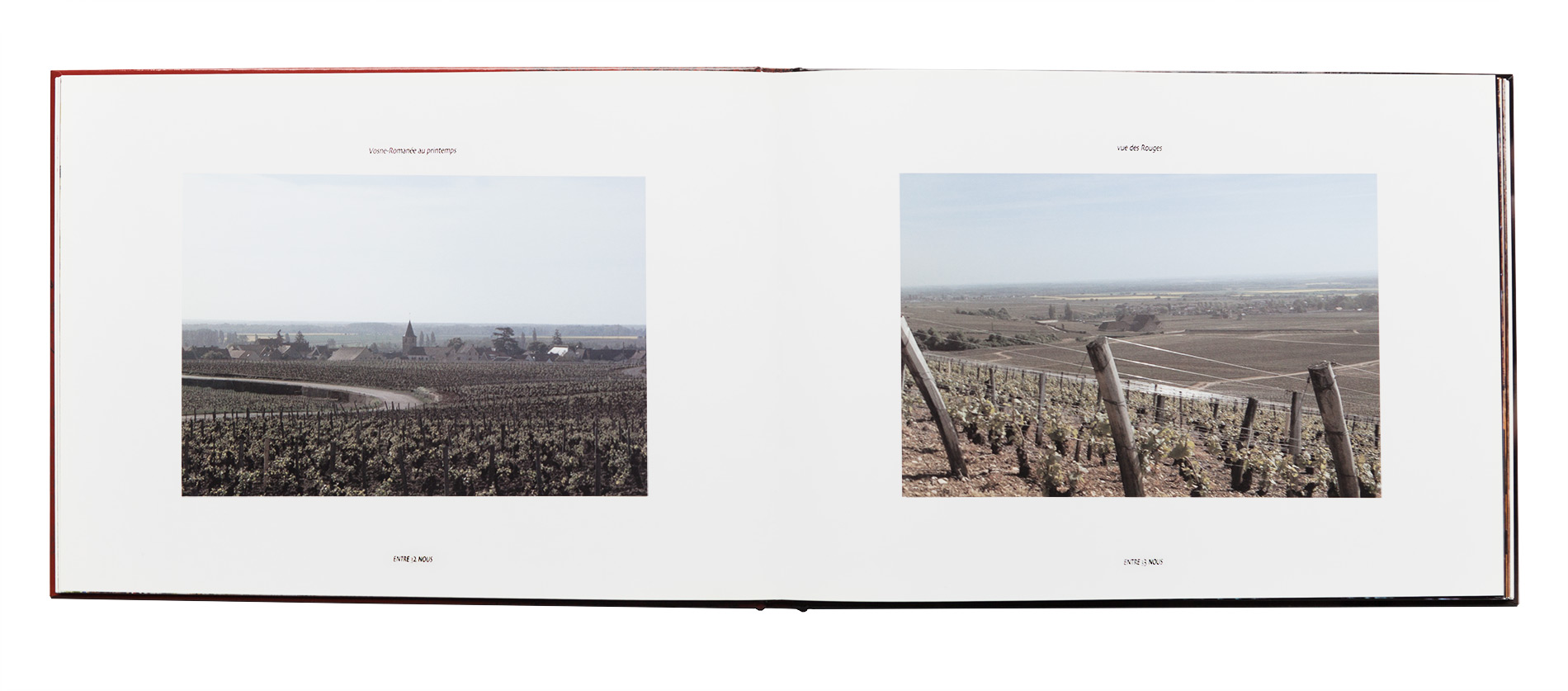

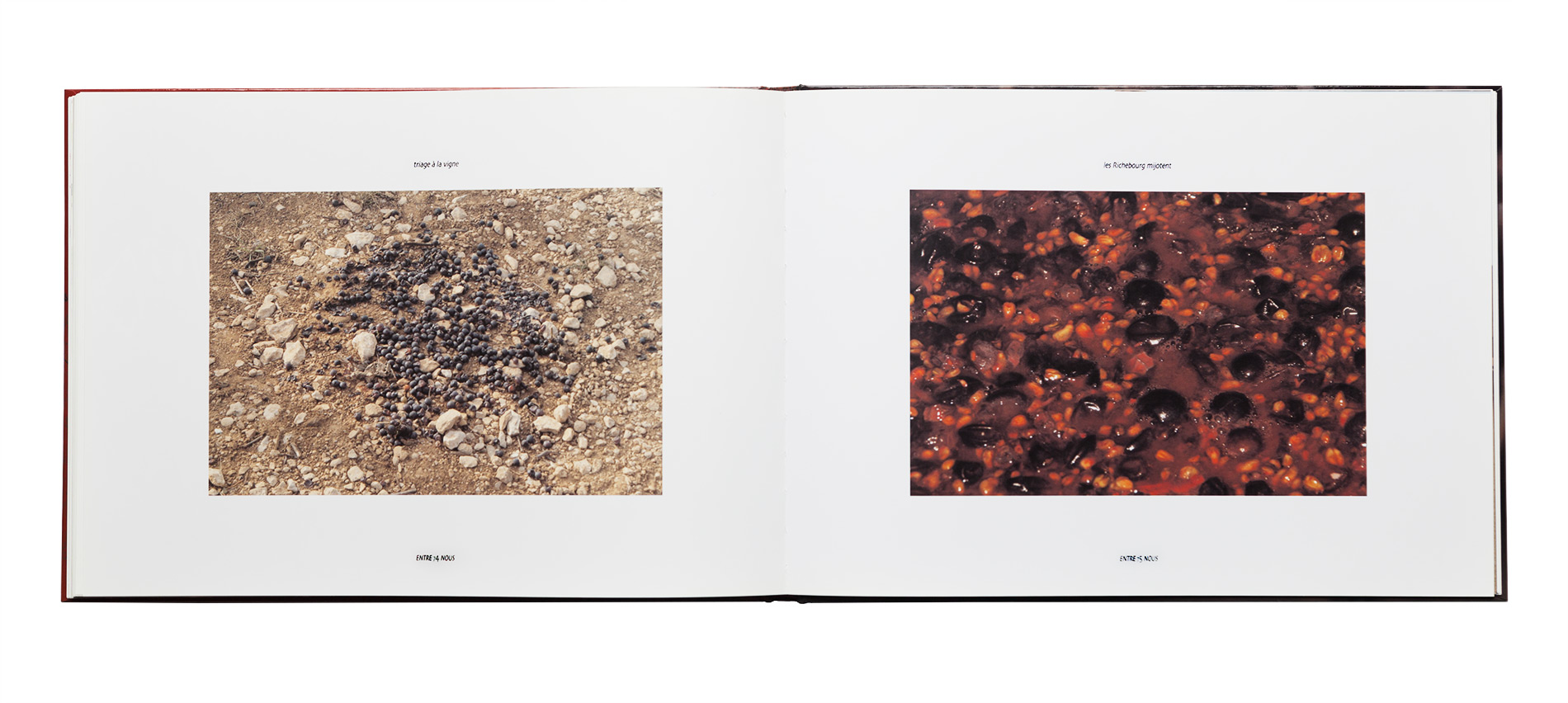

Seven years ago, I met the French winemakers Étienne and Marielle Grivot at a cottage party in Lac Estérel, Quebec. When they learned that I would be in Paris later that year, overseeing a ceramic installation for the department store Printemps, they insisted I overnight at their Burgundy estate.

I arrived with some trepanation, knowing that, although I have an appreciation for fine wine, I was far being from a connoisseur. The couple greeted me warmly and we sat down at the family kitchen table.

Just before we began the hearty main course of duck confit, Étienne opened a new bottle and poured me a glass. From the first sip, I felt instantly transported.

What were my thoughts, they asked, and I shyly responded that I lacked the wine vocabulary to describe them. “Everyone has their own words,” said Étienne. “You felt something. Tell me what it was.”

I explained that I heard voices rising in ecclesiastical song, the notes flowing like silk through the serenity of a cathedral. I could smell its wood and the heady perfume of incense. When I’d finished my description, they were silent for a moment and finally Marielle exclaimed, “She’s good!”

They explained that the stones used to build the region’s gothic churches were pulled from the grape-growing soil. The wood of the pews is the same oak used to build wine barrels. This is the very definition of terroir – that the elements of the region influence the flavour of the grapes.

“Those things you described,” he assured me, “are all in this wine.”

by pascale girardin photography by stephany hildebrand

What happens when you launch an artistic challenge to do nothing.

My own version of Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit (see “Scream at the Wall”) came 10 years ago, when I made up a batch of stickers displaying empty parenthesis. The aim was to celebrate nothing.

At the time, all my energy was going into being busy: taking courses, working on projects and attracting attention to my business. The Internet was a new tool, but it was already clear that fame and fortune could be ours through online self-promotion and publicity. Today we’re used to branding ourselves on social media. But, even then, I had the sense that without the occasional detox, the production and consumption of digital content could be unhealthy. I needed a time out.

Zen Buddhism invites us to walk the tightrope between action and inaction, meaning and non-meaning. Because we don’t have words for it, we use the term “nothing.” But nothing really means “no thing.” Meditation is all about drawing balance from that space – it’s the idea I wanted to capture.

So in the then-burgeoning blogosphere, I sent out a call to my artist acquaintances asking them to join me in a celebration of nothing. I didn’t receive much response (unless you want to get Meta and say that my challenge was universally accepted). In truth, only one person took me up on it. A dancer friend climbed to the top of Montreal’s Mount Royal and performed there… for no one.

Today we’re used to branding ourselves on social media. But, even back then, I had the sense that without the occasional detox, the production and consumption of digital content could be unhealthy.