N° 6

Power

September 2018

by pascale girardin Photo by stephany hildebrand

Empowerment is a word that gets a lot of air time these days.

Empowerment is a word that gets a lot of air time these days. It’s associated with big movements like #MeToo, #BLM and #TimesUp, and it emerges in smaller, more subtle contexts. As I write this from the lounge of a popular Montreal music venue, I’m aware that a poster in the restroom advises patrons who “feel threatened in any way” to alert the bartender. Empowerment in the feminist movement has often come to represent, not even a desire for power, but simply for wellbeing. It’s about defining safe and healthy spaces.

This got me thinking about what the word “power” actually means. There’s the traditional definition that we associate with dominance. But power, in language, takes many forms. As a ceramicist, I’m interested in the ways that this notion manifests. To do my work, I require physical power, the strength to prepare the clay by wedging it a hundred times over (as you’ll read about in Thin Edge of the Wedge). There’s willpower, the ability to self-administer discipline, which my interview with kickboxer Carline Pierre Jacques in Defining Self reveals can be utterly transformative. Then there’s staying power, the idea that small actions over time create a profound impact. This has been as true for me in my 22 years of ceramics as it has been for the mill in Sanbao, China (described in The Shape of Water) from which a tiny trickle is all it takes to pommel some of the world’s finest porcelain clay into being.

“Drift” is my way of explaining how meandering thoughts can crystallize into a fully formed idea. It’s the origin of creative thinking and my mantra for daily life.

I invite you to drift with me.

Pascale Girardin

There’s the traditional definition of power that we associate with dominance. But power, in language, takes many forms.

by pascale girardin photos by stephany hildebrand

The process of preparing clay is as much an artform as the works it produces.

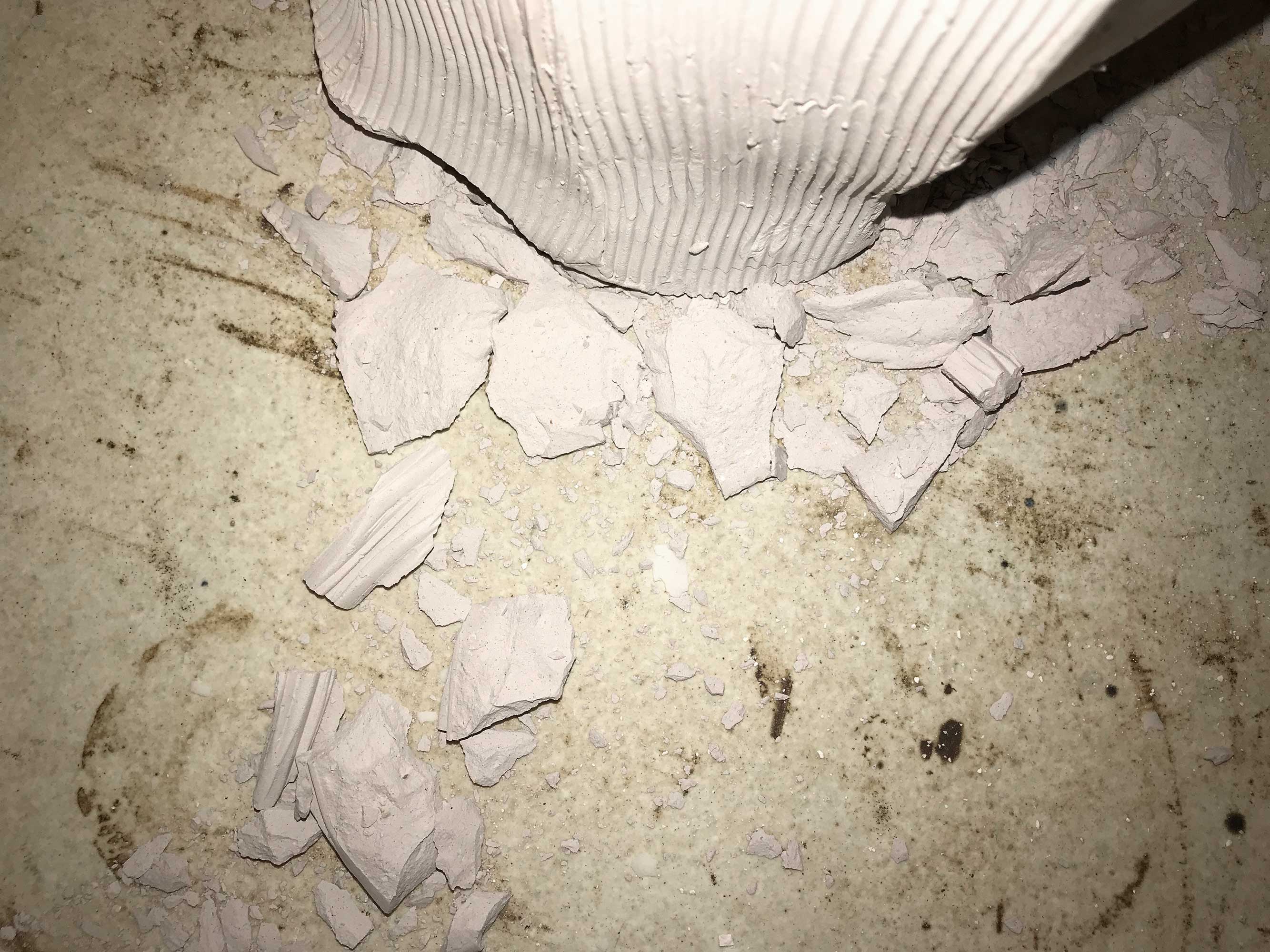

No piece of fresh clay can be hand sculpted, molded or wheel formed without going through the process of wedging. To prepare the clay, the ceramicist must first work it into malleability. It’s a bit like kneading bread, except, whereas the goal there is to work air into the dough, in wedging the objective is to take air out and homogenize the clay body. Trapped air pockets can have devastating effects, which can ultimately cause a nearly finished piece to explode in the kiln—obviously not what you want after you’ve lovingly coaxed a work of art into existence!

Wedging is itself an artform. The experienced ceramicist must be able to read the clay well enough to know when she has reached the precise balance between just enough, so that the clay is free of air bubbles, but not so much that it becomes dry and fatigued. Its density must be consistent and, at a microscopic level, the individual platelets of the clay must align to prevent the pieces from warping as they dry.

Wedging is an intensely physical process, requiring not just the hands, but the whole body. (I remember the soreness in my abs when I first started to learn.) There are different types of wedging styles, but I prefer the Japanese method of spiral wedging. Here, the left hand holds the clay laterally while the right pushes it forward. This technique makes use of body weight over muscle strength. In that way, wedging shares a similarity with the martial arts’ philosophy of using minimum energy to achieve maximum power. And trust me, you need that edge to keep it up for the 120 or so manipulations required to prep a single piece of clay!

I have long appreciated the ritual of wedging for the mental preparation it provides, and the connection it builds between artist and material. When the clay has been wedged, it has a distinct shape that is at once raw and beautiful. That form is something I’m celebrating in a new series. Called “Prologue,” the pieces are composed of clay that I cut after wedging, then reassembled. The finished works give insight into the individual character present in each and every block of clay.

Wedging is itself an artform. The experienced ceramicist must be able to read the clay.

by pascale girardin photo by stephany hildebrand

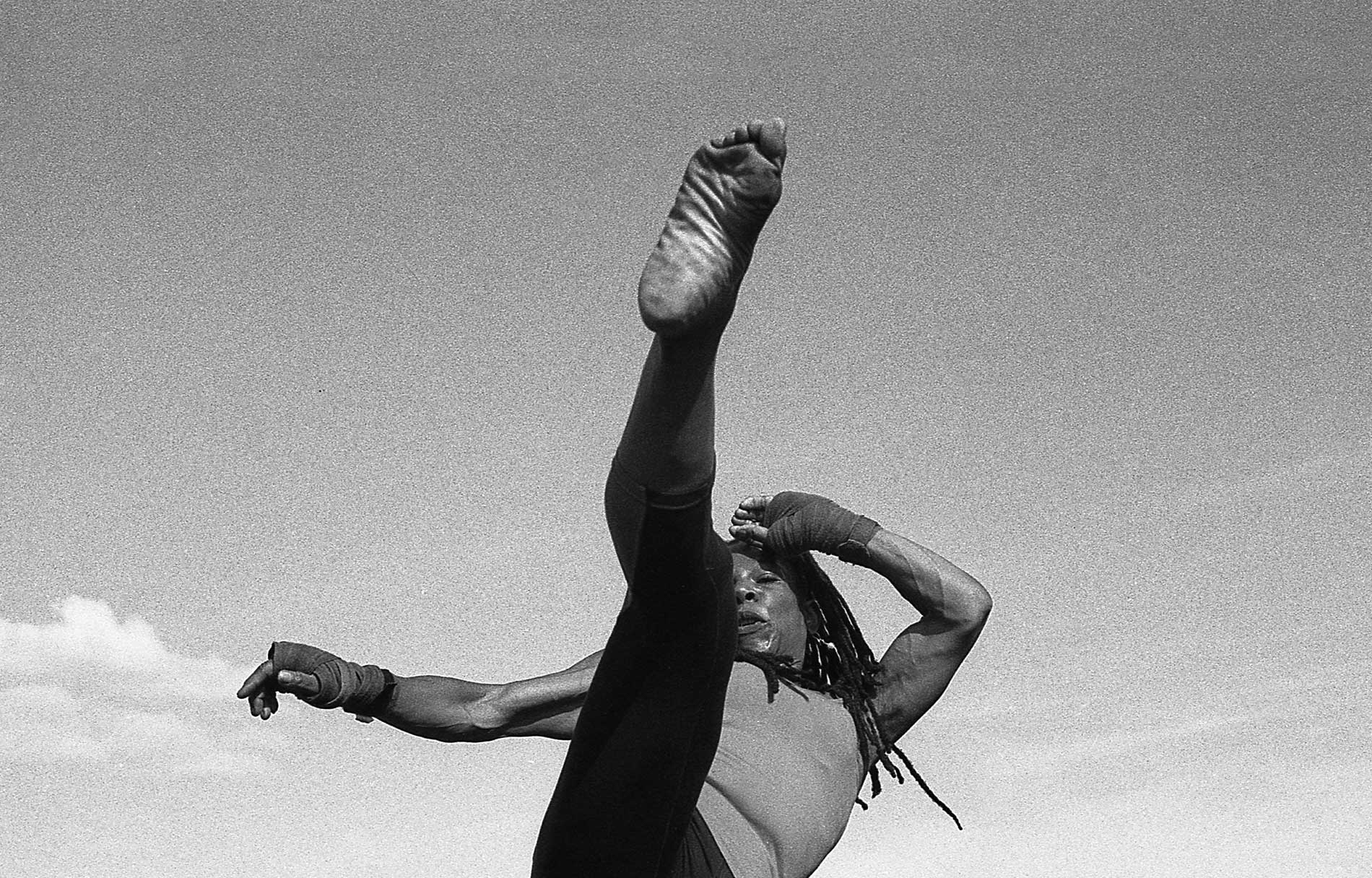

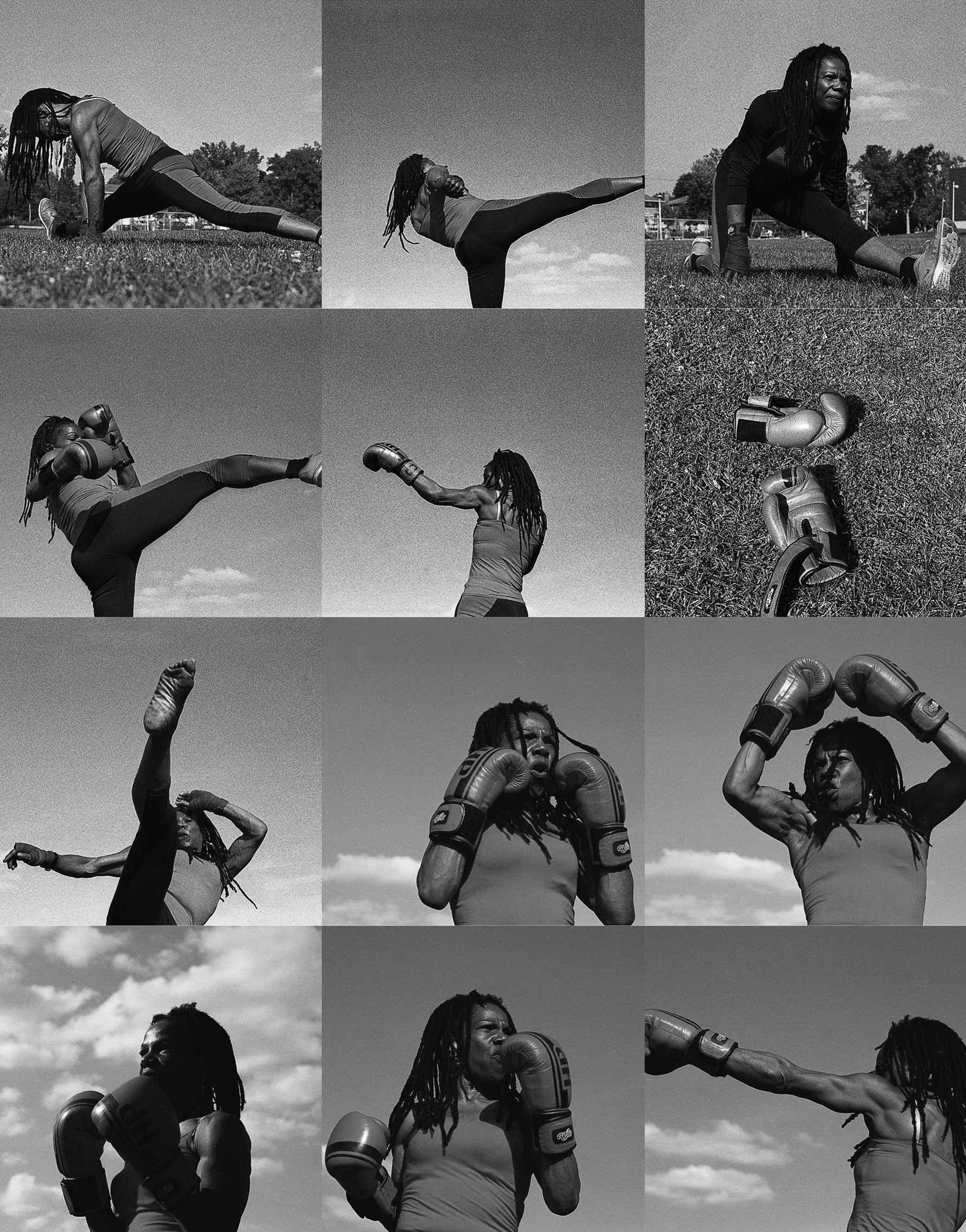

Through kickboxing, Carline Pierre Jacques goes beyond physicality to help women develop their inner strength.

Before Carline Pierre Jacques took her first kickboxing class, she says “I was gaining weight, my life was out of control, my marriage was on the rocks and I had a boss from hell.” But the highly demanding sport turned her life around in many unexpected ways. Jacques was the only woman in her class, but she felt women especially could benefit from kickboxing. In 2011, she founded the Montreal studio Amazon Fitness, focused on teaching empowerment and self defense. Today, Pierre Jacques’ method of training goes beyond the physical, so that the power that her clients develop can impact every aspect of their lives. Here, she describes her experience in her own words.

The most amazing thing about a fighter is not winning or losing, but facing your opponent. In kickboxing, we learn to practice, to throw a punch a million times and start over again until it becomes effortless. We learn to conquer fear and take hits. We learn to roll with the punches or back down because knowing when not to fight is just as important.

Kickboxing changed my life and it changed my world view. When I joined my first class, I had suffered a series of unfortunate events and was depressed. I was gaining weight and no amount of dieting or exercise was helping. But I was immediately swept up in the demands of the sport. Soon weight loss ceased to be an issue. My goal became instead to make my body strong, since I was the only girl in the class and had to keep up. Through my practice, I was aware that I was becoming more resilient. I was learning to get up when life knocked me down.

The most amazing thing about a fighter is not winning or losing, but facing your opponent.

We live in a world that takes the body for granted. We know it’s important to nurture the soul, but if you nurture the body, you’re considered vain. We separate spirituality from our physical selves. But, for athletes, strengthening and cultivating our bodies is spiritual. It’s being in the zone, in the moment.

I was transformed by kickboxing. It made me open my own business. Amazon Fitness is a forum where I encourage women to love themselves, to build strong muscles and to create beautiful bodies. I teach kickboxing, body toning, aero boxing and self-defence, since it’s important that all women learn to defend themselves. But it’s really about creating the warrior women of today.

Écrasement I – 2013 Porcelaine, glaçure, pigments / Porcelain, glaze, pigments 14.3 x 38.5 x 22 cm. Private collection Photo: David Bishop Noriega

Artist Laurent Craste uses acts of violence to create delicate ceramic sculptures that pack a powerful message.

Montreal-based Laurent Craste has defined his ceramic work by destroying what he creates. Craste puts his reproductions of historic vases, busts and other objets d’art through extreme abuses. Those might include trampling, stabbing, defacing with graffiti, beating with a baseball bat or even ramming with a brick. Even so, the pieces remain recognizable as decorative objects. By willfully corrupting these icons, he disrupts our notions about the historical, social and aesthetic value they represent, and creates a new aesthetic in the process. Here is independent curator Pascale Beaudet on Laurent Craste.

Portrait of Laurent Craste with Iconocraste - O Photo: David Bishop Noriega

Laurent Craste explores the notion of power by focusing on the dominant French classes of the 18th and 19th centuries, who commissioned very beautiful objects d’art, including vases from the famous French porcelain manufacturer in Sèvres. The artist is particularly interested in how the elite of that time used economic power and aesthetics as instruments of propaganda.

And while his works examine the power the elite exuded over the masses, they are also a commentary on the latter’s retaliation. The violent acts that Craste subjects his reproductions to draw reference from peoples’ uprisings of the French Revolution of 1789 and the Paris Commune of 1871, during which works of art and buildings, once held by the upper classes, were routinely destroyed.

In his vases, we see the objects’ delicacy contrasted with the solidity of the tool used to disfigure them. We also see a juxtaposition of eras and methods of fabrication: the hand-crafted objects of the 18th and 19th centuries, with the tools machined in 20th-century factories.

Révolution III – 2016 Porcelaine, glaçure, hache Porcelain, glaze, axe 77 x 30 x 43 cm. Photo: Daniel Roussel

To determine the mode of destruction for each piece, Craste develops his works in reverse. Both the clay and the tool must be tested in the kiln. It means conducting numerous experiments—and also suffering many losses. Ultimately, the material composition of the tool determines at which stage of the process it will be integrated into the piece. As to the choice of tool, it’s the shape of the decorative object that determines it.

Craste says that, given the number of losses, which can account for nearly half of his overall production, his greatest satisfaction is in realizing that one successful piece. Conversely, he feels an intense frustration when the object collapses. It’s at that point that the porcelain exercises its power over the artist.

by pascale girardin photos by pascale girardin

From a porcelain mill in China, we learn about the remarkable power of small actions.

For nearly two thousand years, the town of Sanbao in China’s Jingdezhen prefecture, has produced the ultra-white porcelain used by the country’s royal households. But while dynasties rose and fell, the work produced in Sanbao endured. Today, the location is considered the world capital of pottery and is home to a prestigious international ceramics institute.

Earlier this year, while completing an installation in Shanghai, I had the opportunity to visit Sanbao and watch its traditional method of clay production. I witnessed the clay—the rare streak of porcelain known as kaolin—being collected into water basins. I saw the floor covered with the silky, white substance, and watched as it was shaped into squares and dried for distribution. But the most impressive part of the facility, now a Chinese heritage site, was its hammer mill. Set in motion by a mere trickle from a nearby creek, this water wheel powers several impressively-sized mallets that pummel the raw mud into its purest form.

It reminded me that we can all strive to be a little like that tiny trickle. Water has its ways. It can freeze inside a rock and split it in half. It can drip for a thousand years and make a pool in stone. When you pour it in front of an obstacle, it will find the simplest way around it. What a wonderful analogy for power!

by pascale girardin photos by stephany hildebrand

What working in a fussy medium has taught me about staying power.

I chose to make a career out of mud. To look into that mud and say I see beauty, I see luxury, I see pieces that will grace the world’s finest hotels, restaurants, shops and private residences. My relationship to that mud has been the longest of my life. That requires staying power.

How many things can go wrong on a ceramics piece? Let me count the ways. Pieces can explode in the kiln. They can be maimed by the shrapnel of other explosions. They can sag or warp. They can get pitholes, or bubble, or split. Glazes can come out wrong. They can be glossy when you want matte, opaque when you want translucent, and vice versa. The colours can drip and cake. They can expand at a different rate to the clay and cause the ceramic to fracture.

Of course, none of this shows up right away. To see the extent of the damage, you have to have patience. You have to wait. The kiln fires over a 12-hour cycle, at 1,200 degrees Celcius. And, before you can even open the door, you must give it another 12 hours to cool. Only then, 24 hours later, does every error committed to the piece, every imperfection of material, show up. A flaw may have been introduced months earlier in the wedging, the drying, the first firing, the second. To know what went wrong, you need to have a good memory. You have to take lots of notes.

Some of the flawed pieces get put aside. I’ll think that maybe, given time, I’ll like them. Some, I discard because I’ve learned something new. Occasionally I’ll have a premonition that something has gone wrong, and, even before the kiln door opens, I’ve moved on. You can’t cry over spilled milk in this craft. If you do, you’re not in the right field. You will fail the clay and the clay will fail you. All you can do is look into the next batch of mud and dream.